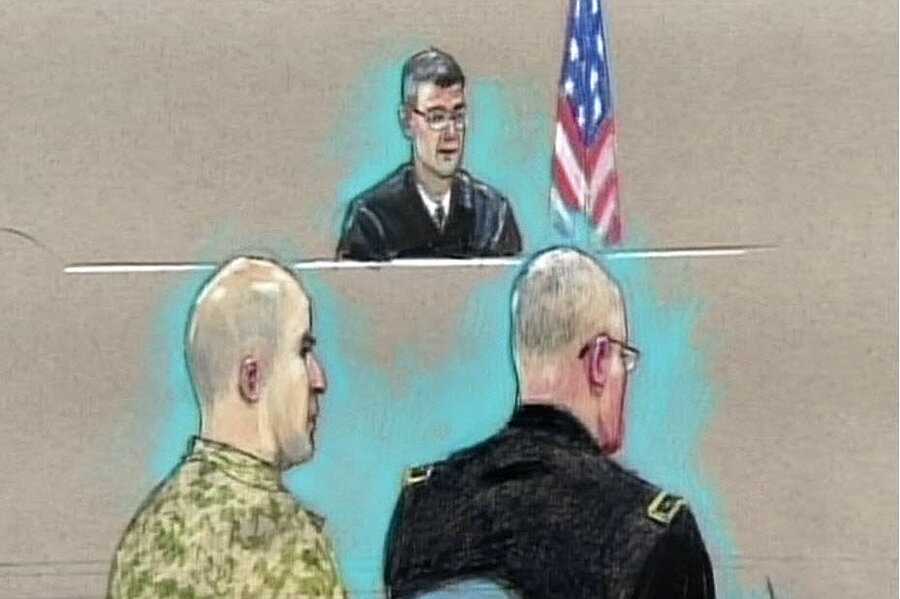

Why military judge has hands full with Nidal Hasan court-martial

Loading...

US Army Maj. Nidal Hasan, a psychiatrist accused of murdering 13 fellow soldiers in a hail of gunfire at Fort Hood in 2009, will have a chance to be both star witness and star defense counsel in a long-awaited court-martial that looks ready to pit Western justice against justifications for Islamic jihad.

After determining that Hasan is mentally and physically fit to defend himself, the military judge, Col. Tara Osborn, is now weighing the extent to which she’ll allow him to pursue his main defense: that he was justified in killing US soldiers about to deploy to Afghanistan to prevent the imminent deaths of Taliban soldiers.

Undoubtedly, military justice experts say, Hasan will have opportunity both in arguments and cross-examination to make bolder statements, some that may try to weave legitimate legal theory into political or religious ideology in order to use the trial “as a platform to advance radical jihad,” as Jeffrey Addicott, director of the Center for Terrorism Law in San Antonio, told the Monitor’s Amanda Paulson on Monday.

While Judge Osborn has the power to limit testimony to the facts at hand, former military lawyers and legal experts suggest that it will be a difficult court-martial to manage, mainly because it exposes attack survivors to cross-examination by the same man whom they say pointed weapons at them and opened fire while yelling “Allah Akbar,” Arabic for “God is great.”

One expert on military courts, speaking on background, says the trial “is going to be an exercise in control, moment to moment.”

Osborn “has got to figure out where to draw the line … [if] she wants to prevent this from turning into a complete circus without depriving a defendant who is accused of a serious crime of his right to defend himself,” adds Aitan Goelman, a former US Department of Justice terrorism prosecutor. “There doesn’t seem much question about whether this guy opened fire on a bunch of soldiers … so the legal battle that’s going to be fought is going to be atypical. Despite the whole idea that his defense is that he came to the defense of others, [it’ll create] an opportunity for him to make his political or theological case.”

Osborn’s task may mirror in part that of US District Judge Leonie Brinkema, who shepherded the civilian trial of Zacarias Moussaoui, the so-called 20th 9/11 hijacker. At his 2006 trial, Mr. Moussaoui berated the court, cited Islamic law, and even threatened the jury while cursing his own defense team. Many doubted that the US could fairly try a terrorism suspect, while others said Judge Brinkema went too far in allowing Moussaoui’s rants. Moussaoui was sentenced to life in prison.

Before allowing Hasan to defend himself, Osborn spent more than an hour Monday grilling him about his request, suggesting several times that he would be better off if his appointed military lawyer were to handle the courtroom. The judge retains the right to hand his defense back to the appointed military lawyer if Hasan proves unable to act as his own lawyer or unwilling to stick to the facts of the case.

Meanwhile, appeals cases are already being drafted, legal experts say, given Monday’s decision to allow Hasan to defend himself and the earlier fight about whether Hasan should be able to wear a beard or be forced to shave it, given that he still falls under the purview of Army regulations that forbid beards for officers.

Osborn is also poised to rule on whether to delay the court-martial to let Hasan have time to prepare. He requested a three-month delay, even though he had earlier told the court that he was ready to proceed immediately.

To be sure, many Americans may shudder at the prospect of giving Hasan a media spotlight in which to condemn American soldiers or even to foment jihad against the US – especially given recent urgings by Al Qaeda elements in the wake of the Boston Marathon bombings for American Muslims to attack US targets on their own. Hasan himself is a Muslim American, was born in Virginia.

Despite military judges’ latitude to keep outbursts to a minimum, the system is not equipped to prevent “someone from using it as a platform,” Mr. Goelman says. It gives defendants “a certain amount of latitude to use the system for their own ends.”

Some Army lawyers concede that such scenarios may be hurtful, even dangerous. But they also suggest that limiting Hasan’s rights would undermine American values, which are the key push-back against extremists' rationale for jihad against the West.

“I think we sleep better at night because we allow these kinds of trials to happen,” says retired Maj. Gen. John Altenburg, a former Army lawyer and past Appointing Authority for Military Commissions in the Office of the Secretary of Defense. “We try to be dispassionate, and when you finally convict someone like that, assuming he’s convicted, nobody looks back and says, ‘Wow, we kind of ramrodded him.’ Nobody can say he didn’t have his day in court.”

During his trial, Moussaoui spewed threats and venom, and, in one court paper, characterized Judge Brinkema as having “acute symptoms of Islamophobia with complex of gender inferiority.” But he later said in a court filing he was surprised that an American jury would spare his life. "I now see that it is possible that I can receive a fair trial even with Americans as jurors," he conceded.