Why juvenile incarceration reached its lowest rate in 38 years

Loading...

Fewer young Americans are behind bars than at any point since 1975, partly because of lower rates of juvenile crime and a shift away from interventions focused on long-term incarceration.

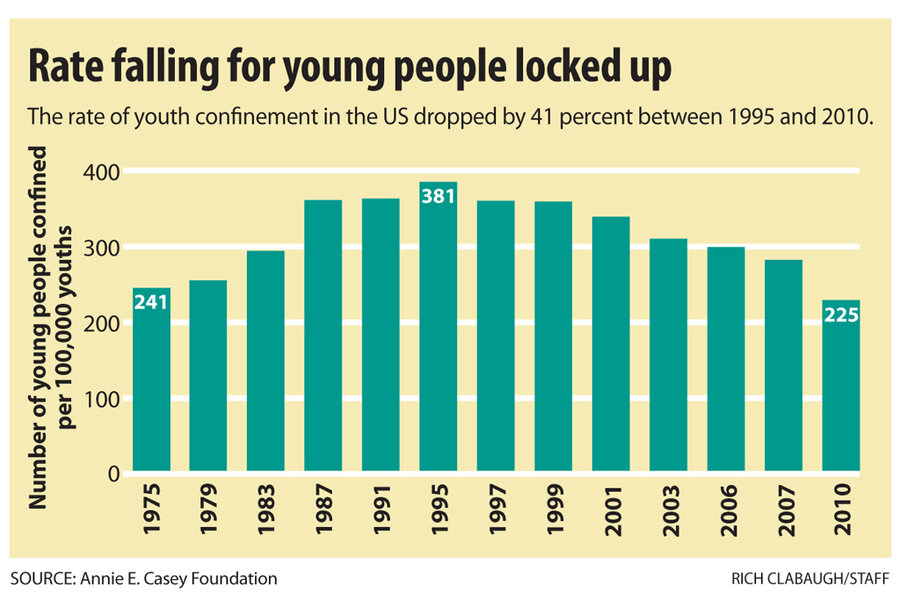

The number of young people in a correction facility on a single day dropped from a high of 107,637 in 1995 to 70,792 in 2010, according to a new report from the Annie E. Casey Foundation that used data from the US Census Bureau. The incarceration rate – the number of young people confined per 100,000 youths – dropped by 41 percent in the same period.

The trend might be stronger than the data show, says Bart Lubow, director of the foundation’s Juvenile Justice Strategy Group. Some of the biggest decreases in youth incarceration in some states have occurred in the past two years, and those numbers are not included in the report.

The main reasons behind the declining numbers:

- A shift in thinking about the best ways to handle young people who break the law.

- A sustained period of decreasing juvenile crime.

- Fiscal pressures on state governments that have many people – including conservatives who, in the past, espoused tough-on-crime policies – clamoring for less-expensive alternatives to mass incarceration.

“It’s the confluence of all those factors” that has led to the sustained decrease, says Mr. Lubow, though he notes that the report shows big disparities between states.

Looking at the period between 1997 and 2010, for instance, seven states (Arizona, Connecticut, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Jersey, and Tennessee) saw their youth incarceration rates go down by 50 percent or more, while six (Arkansas, Idaho, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, and West Virginia) actually bucked the trend and had increased rates for the same period.

Several of the largest states, with the biggest overall numbers of youths behind bars, also saw big drops, notably California and New York.

Still, the overall decline in juvenile confinement occurred in all regions of the country and across all of the five largest racial groups. Rates for African-American youths decreased by 38 percent, rates for Hispanic youths by 51 percent, and rates for non-Hispanic white youths by 37 percent. Still, African-Americans, Hispanics, and American Indians remain far more likely than white youths to be confined. (African-American youths, in particular, are five times more likely than their white peers to be incarcerated.)

While the long-term trend is both striking and encouraging – particularly given research about the negative consequences of unnecessarily locking up nonviolent youths – the United States still has a long way to go, says Lubow.

“Even with the drops we’re describing in this report, the US, compared to similarly governed countries like those in Western Europe, has a much, much higher [youth] incarceration rate than any of those places,” he says.

America’s incarceration rate for juveniles is 18 times greater than that of France, and more than seven times greater than that of Britain. It’s hard to even compare it with the juvenile incarceration rates in places like Finland or Sweden, where young offenders are seldom locked up.

“We are in a different league, and we have a long way to go if what those countries do is reflective of what an enlightened, compassionate country – determined not just to protect public safety but to [offer] its kids the best opportunities for maturing into adulthood – does,” says Lubow.

He and other juvenile-justice reform advocates say large-scale incarceration not only, in many cases, leads to abuse and harsh treatment for the children and teenagers confined, but is also needlessly expensive and poor in terms of long-term public safety, according to research.

Beds in juvenile correction facilities cost, on average, about $88,000 a year.

A substantial percentage of young people who end up in the corrections system may have a history of chronic misbehavior, but haven’t shown any tendency toward violence, says Lubow – and as they are pulled into the correctional system, their recidivism rates and long-term outcomes become worse.

“It’s hard to imagine you couldn’t arrange a more effective set of interventions for those kids that would also have a greater positive influence on their well-being,” says Lubow, who advocates interventions that treat an offender within his or her family and still provide appropriate consequences.