'Torture memos' author can't be sued for harsh interrogations, court rules

Loading...

A federal appeals court ruled on Wednesday that the author of the so-called “torture memos” during the Bush administration could not be sued by an American citizen who claims he was tortured while being held without charge in military detention for three years and eight months.

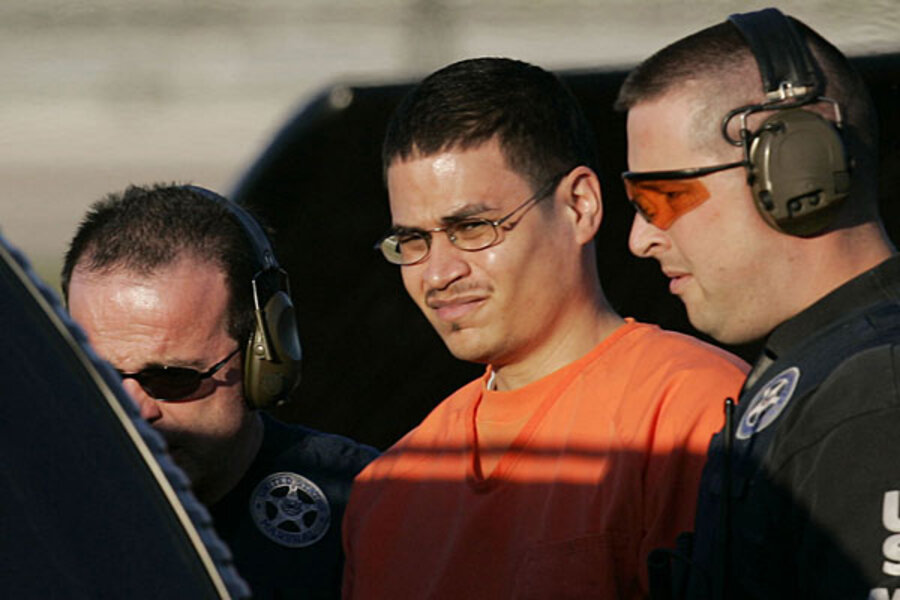

José Padilla and his mother, Estela Lebron, had filed suit against former Deputy Assistant Attorney General John Yoo for allegedly creating a legal justification for Mr. Padilla’s open-ended detention and the coercive interrogation methods used to try to break him psychologically.

Padilla was accused of plotting with Al Qaeda to conduct a “dirty bomb” attack on a US city. The allegation, which has never been substantiated, was used to justify his treatment.

Padilla was initially detained in the criminal justice system, but after a court ruled in his favor, he was designated an enemy combatant by President Bush and held incommunicado at the Navy brig near Charleston, S.C.

The US government believed he had information about Al Qaeda that might help prevent future terror attacks on the US. He was subjected to extreme isolation, including sensory confusion techniques, sleep deprivation, and stress positions. Mental-health professionals who examined him after his release from the brig said he had suffered severe and perhaps permanent psychological damage from his treatment as an enemy combatant.

The lawsuit sought two goals. His lawyers wanted a judge to declare that Padilla’s treatment violated US constitutional protections. They also sought nominal damages of $1 from Mr. Yoo, now a constitutional scholar and law professor at the University of California at Berkeley.

In throwing the lawsuit out, the panel of the Ninth US Circuit Court of Appeals said that Yoo was entitled to qualified immunity because it was not clearly established in the early years of the Bush administration that Padilla’s treatment amounted to torture.

“We assume without deciding that Padilla’s alleged treatment rose to the level of torture,” Judge Raymond Fisher wrote for the three-judge panel. “That it was torture was not, however, beyond debate in 2001-03.”

He added: “In light of that debate…, we cannot say that any reasonable official in 2001-03 would have known that the specific interrogation techniques allegedly employed against Padilla, however appalling, necessarily amounted to torture.”

The Ninth Circuit panel stressed that it was “beyond debate” in 2001-03 that it was unconstitutional for the government to torture an American citizen. But the court said it was not “clearly established at that time that the treatment Padilla alleges he was subjected to amounted to torture.”

The 2002 “torture memo” set broadly permissive standards giving significant leeway to interrogators. It says a subject would have to experience pain equivalent to organ failure to prove torture.

The memo also set broadly permissive standards for the infliction of mental harm.

“The development of a mental disorder such as post-traumatic stress disorder, which can last months or even years, or even chronic depression, which can last a considerable period of time if untreated, might satisfy the prolonged harm requirement” to prove torture, the memo says.

Three mental-health experts who examined Padilla have said his mental condition exceeded that standard. His detention and interrogation left him with severe mental disabilities, they say, from which he may never recover.

In addition to Judge Fisher, the Ninth Circuit panel included N. Randy Smith and Rebecca Pallmeyer, a federal judge in the Northern District of Illinois.

The judges said that while the constitutional rights of convicted prisoners and persons subject to the criminal justice system were well established, “it was not beyond debate at that time that Padilla … was entitled to the same constitutional protections as an ordinary convicted prisoner or accused criminal.”

The court said that someone designated as an enemy combatant by the president – regardless of whether he is a US citizen or not – is not automatically entitled to full constitutional protections.

“Padilla was not a convicted prisoner or criminal defendant; he was a suspected terrorist designated an enemy combatant and confined to military detention by order of the president,” the court said. “He was detained as such because, in the opinion of the president … Padilla presented a grave danger to national security and possessed valuable intelligence information.”

“We express no opinion as to whether those allegations were true, or whether, even if true, they justified the extreme conditions of confinement to which Padilla says he was subjected,” Fisher wrote. “In light of Padilla’s status as a designated enemy combatant, however, we cannot agree with the plaintiffs that he was just another detainee” entitled to full constitutional protection.

“Given the unique circumstances and purposes of Padilla’s detention [and in light of a World War II legal precedent], an official could have had some reason to believe that Padilla’s harsh treatment fell within constitutional bounds,” the appeals court said.

The court said government officials must be given ample “breathing room to make reasonable but mistaken judgments about open legal questions.”

Citing that principle, the court concluded that Yoo may not be sued – even by US citizens arrested on US soil who were subjected to controversial interrogation tactics after being removed from the criminal justice system to facilitate their open-ended coercive interrogation.

Padilla was released from the brig and transferred to Miami to face charges that he participated in a conspiracy to provide material support to Al Qaeda. He and two co-defendants were convicted in 2007. Padilla is serving a 17-year prison term.

His criminal case is being appealed to the US Supreme Court. He also has a pending appeal at the high court concerning a civil lawsuit filed against Defense Department officials allegedly responsible for his treatment in the brig.

“The Ninth Circuit’s decision confirms that this litigation has been baseless from the outset,” Yoo told the Associated Press. “For several years, Padilla and his attorneys have been harassing the government officials he believes to have been responsible for his detention and ultimately [his] conviction as a terrorist. He has now lost before two separate courts of appeals, and will need to find a new hobby for his remaining time in prison,” Yoo said.