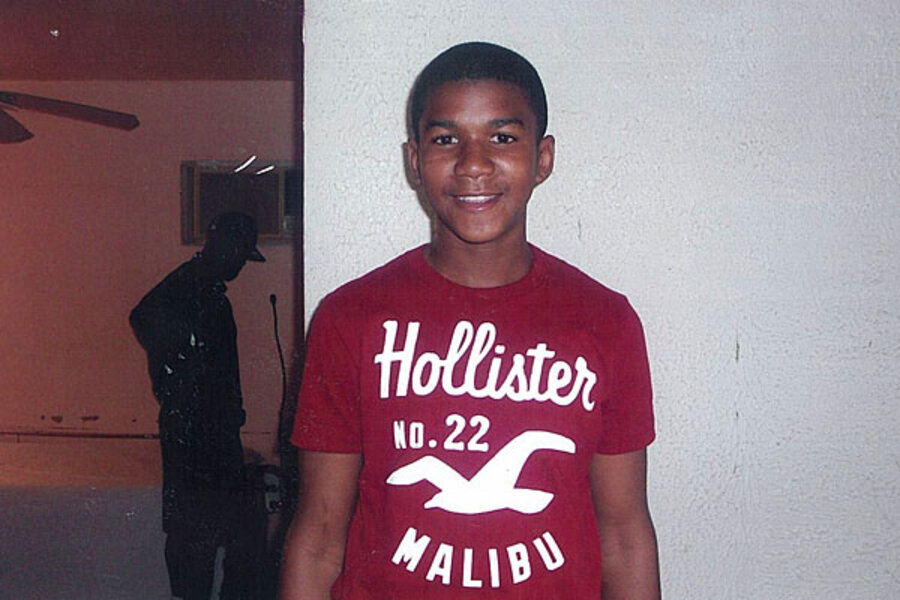

Trayvon Martin case: use of Stand Your Ground law or pursuit of a black teen?

Loading...

The shooting death of Florida teenager Trayvon Martin is no longer in the sole hands of local law-enforcement officials, meaning the wheels of justice appear to be moving, after a three-week delay, toward a fuller investigation of whether the shooter killed the 17-year-old in self-defense.

On Tuesday came the announcement that Florida's Seminole County will convene a grand jury on April 10 to look into the case, even as a team from the US Justice Department's civil rights division arrived in Sanford, Fla., the community where Trayvon died Feb. 26 after he was shot by a self-appointed neighborhood watchman.

The Justice Department would not ordinarily investigate such an incident, but the fact that Trayvon was black and the alleged shooter, George Zimmerman, is part white, part Hispanic – and that local authorities declined to press charges against Mr. Zimmerman, even though Trayvon was unarmed – opens the door to a civil rights investigation on grounds the teenager came under suspicion primarily because he is African-American.

Protests, rallies, and official pressure have been building ever since the police in Sanford declined to arrest Mr. Zimmerman. Before the shooting, Trayvon had been walking from a convenience store back to his father's fiancée's house in a gated neighborhood, with nothing more than a bag of Skittles in his pocket.

The 911 tapes, plus a report Tuesday from a girl who says she was talking with Trayvon on the phone just before the shooting, suggest that Zimmerman may have run after the teen. If true, that could allow the Justice Department to help draw the line on so-called “Stand Your Ground” laws and reaffirm civil rights protections for young men who draw suspicion by virtue of their skin color.

“The Stand Your Ground law was not intended to authorize vigilante action on the part of neighborhood watch guys when they have suspicions about the motivation of some kid walking through the neighborhood,” says James Wright, a sociologist who studies gun violence at University of Central Florida in Orlando. “To simply say this case is ambiguous and therefore can't be prosecuted opens the door for a lot of nefarious” actions to take place. In that way, he says, “this case could help draw the line between what's right and legally justifiable and what goes beyond that.”

“With all federal civil rights crimes, the government must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a person acted intentionally and with the specific intent to do something which the law forbids – the highest level of intent in criminal law,” the Justice Department said in a statement, upon announcing it would investigate Trayvon's death. “Negligence, recklessness, mistakes and accidents are not prosecutable under the federal criminal civil rights laws.”

The case has sparked outrage across the US, as well as rallies and protests on college campuses and in the Orlando, Fla., area.

While the exact circumstances of the shooting are not clear, the preponderance of evidence seems to point toward Zimmerman overstepping the bounds of the state's Stand Your Ground law, say some legal and criminal justice experts. The law obviates an individual's "duty to retreat" from threatening situations. Zimmerman had made several previous 911 calls about suspicious people in the Retreat at Twin Lakes community.

“He didn't stand his ground; he was hunting,” says Alan Lizotte, dean of the School of Criminal Justice at the University at Albany in New York.

It also turns out that Trayvon was on the phone with a 16-year-old girl just before the incident, according to the lawyer for Trayvon's family, Ben Crump. At a news conference Tuesday afternoon, Mr. Crump played a taped conversation with the girl, in which she recounted what her talk with Trayvon as he walked back to the house that day.

“Why is this dude following me?” she says Trayvon asked. The girl said she suggested that he run, which he did. He stopped running for a moment, then saw Zimmerman again, she reported. At that point, he told her he was just going to walk fast, she recounted. Next, she said, she heard a man ask, “What you doing around here?” The call then ended, and she said she believes that was when Trayvon was pushed and his earpiece fell out.

Zimmerman's father, Robert Zimmerman, has said inferences that his son started the altercation are misleading and false. But as more evidence emerges, including revelations that police did not test Zimmerman for drugs and alcohol before releasing him after a short detention, the police department is coming under more and more criticism for its handling of the case. In the department's defense, Chief Bill Lee has said Zimmerman's bloody nose and bloody head supported his assertion that he was attacked and shot Trayvon in self-defense.

In other developments, voice and audio experts are combing through a series of 911 calls on Feb. 26 in which a voice can be heard calling for help before a shot rang out. The family says it's Trayvon's voice; police have said they believe it's Zimmerman calling for help.

“Because this case is so bizarre, how can [Justice] not do something about this, and at least investigate?” asks Mr. Lizotte. “If you don't look into why police say they can't charge him, what's left? Sort of a Wild West model for law enforcement, where if somebody draws on you first and you're faster, you're OK?”

In Florida, the lawmaker who sponsored the 2005 Stand Your Ground law said Monday that the statute was not intended to protect people who sought conflict, and some Florida legislators have vowed to hold hearings on whether to amend the law.

“No matter what your position is on [race or guns], nobody believes that your rights extend to the right to kill innocent and unarmed children on [public property],” says Professor Wright. “No member of the NRA would disagree with me on that.”

Others say that, as evidence has mounted, the case has become less about the Stand Your Ground law and more about a central civil rights question: If the racial roles had been reversed, would an arrest have been made?

“That's what civil rights statutes are there for, when, in fact, local law enforcement fails to protect the rights of citizens, especially when race seems to be implicated, as it certainly is in this case,” says Bob Cottrol, a law professor and gun rights expert at George Washington University Law School in Washington, D.C.