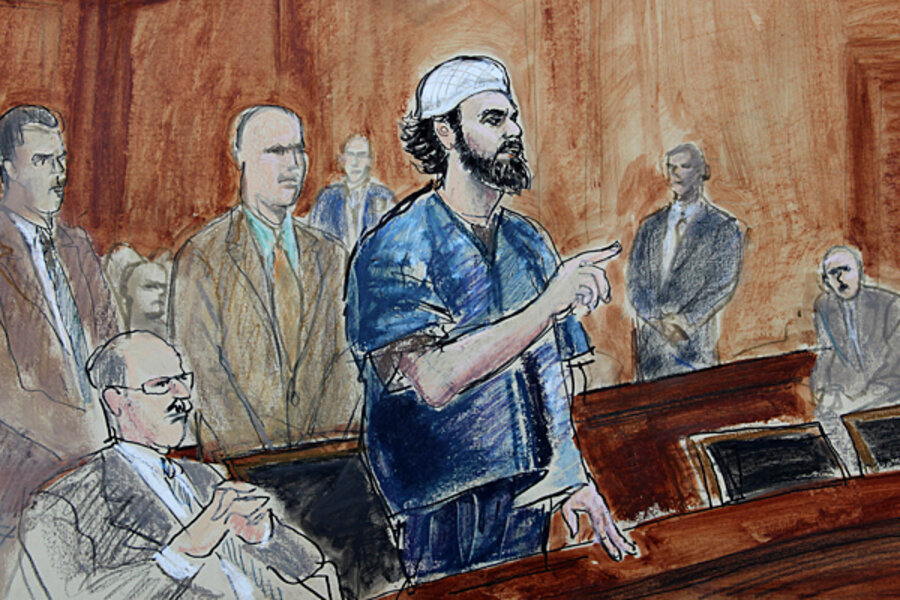

Life sentence for Faisal Shahzad, could join shoe bomber in Colorado

Loading...

| New York

On Tuesday Faisal Shahzad, the unrepentant Times Square bomber, joined at least 35 terrorists in America who will spend the rest of their lives behind the high walls of a super-maximum security prison in Colorado.

His life-in-prison cellmates – although they may never have any personal contact with one another – include Richard Reid, the so-called shoe bomber; Ramzi Yousef, the mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing; and Zacarias Moussaoui, for involvement in the 9/11 attacks.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons will decide Mr. Shahzad’s destination, but he will probably end up in Florence, Colo. – home to a prison called the Alcatraz of the Rockies because it is designed to make escape from its walls all but impossible. If a prisoner is assigned to the most secure part of the prison, he spends about 23 hours a day in solitary confinement. Exercise takes place in what has been described as an empty swimming pool.

In Shahzad’s case, US District Judge Miriam Goldman Cedarbaum had little choice but to send him to jail for the rest of his life, legal experts say. In his court appearances, Shahzad, who pleaded guilty, was defiant. Even on Tuesday, after the judge had suggested he educate himself about whether the Quran wants him to kill innocent people, he replied, “The Quran gives you the right to defend. That’s all I’m doing.”

Shahzad’s attempt at blowing up a vehicle in a busy Times Square on May 1 was considered a serious crime because it would have been deadly had the bomb ignited. As part of the sentencing, prosecutors showed the judge a video of a similar car, loaded with the same kind of explosives, being detonated.

Although Judge Cedarbaum threw the book at Shahzad, his case was unusual because he apparently cooperated with the government after he was arrested, giving them information about the terror camps where he learned how to make bombs.

Normally, when a defendant cooperates with the government, it sometimes leads to lighter sentences, notes Robert Mintz, a former federal prosecutor.

“But his case was an odd juxtaposition of defiance and cooperation,” says Mr. Mintz, now a partner at McCarter & English, a law firm in Newark, N.J. “In all likelihood, the cooperation would not have given him much of a break. It’s hard to imagine a lighter sentence.”

Shahzad’s sentence of mandatory life in prison means he will never be eligible for parole.

“The judge had no discretion. She had to impose a life sentence,” says James Cohen, an associate professor at Fordham University School of Law in New York.

Does a life sentence, in a harsh prison, act as a deterrent for others? So far, it has not been very effective, Mr. Cohen argues.

“With alarming frequency, we will still have suicide bombers and still have them trained, and I suspect the supply is inexhaustible,” he says. “There is no indication they are having any trouble getting recruits for suicide bombings.”

Shahzad would have been eligible for the federal death penalty only if his attempt had been deadly, says Mintz. In fact, he notes, prosecutors prefer the certainty of a life-in-prison sentence to the uncertainty of getting a jury to agree on the death penalty.

The only terrorist who has been put to death in the US in recent times is Timothy McVeigh, the Oklahoma City bomber who was executed in June 2001.