Biden’s ‘historic’ Asia summit confronts an old foe: History

Loading...

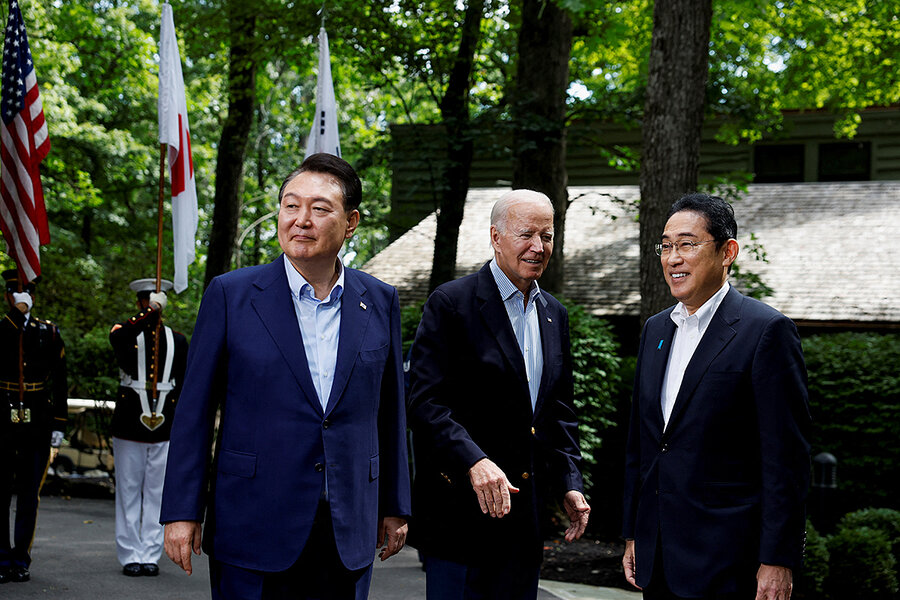

President Joe Biden’s trilateral summit held at Camp David Friday with the leaders of Japan and South Korea could set the stage for a more secure and free Pacific region, while revitalizing America’s Asia presence at a time when many have concluded it is waning.

Indeed, “The Camp David Summit” has the potential to become shorthand for a watershed moment for East Asian security and diplomatic relations, some U.S. officials and regional experts say, in a way similar to how “Camp David Accords” captured a key moment of progress in Middle East peace.

But the question going forward will be whether the one-day summit – hailed by the White House as a “historic first” intending to “institutionalize” deepening relations among the three countries – can live up to its promise.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onA summit between the United States, Japan, and South Korea sought to institutionalize the trilateral relationship. But the relations must overcome several sources of distrust: in Asia of U.S. staying power, in China toward the three allies, and in South Korea of Japan.

“The word that’s been bandied about by the Biden administration and others is ‘historic,’ that this was the first time President Biden was hosting foreign leaders at Camp David, that this was a pivotal moment in assuring that [Japan and South Korea] will continue to be much more forward-looking together,” says Shihoko Goto, director for geoeconomics and Indo-Pacific enterprise at the Wilson Center in Washington.

“The big test will be if, no matter what election results we have in coming years, the spirit and letter of this summit live on. If this survives post-Biden,” she adds, “then this really is historic – for Asia, but also in solidifying that the U.S. continues to be a broker of peace and international cooperation in the world.”

If one is to assess the question of the summit’s promise simply by the concrete steps agreed to by Mr. Biden, Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, and South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol, the answer might seem to be a slam-dunk “Yes.”

The three leaders committed to holding such three-way summits at least once a year. They agreed to hold more joint military exercises around the Korean Peninsula, and to create a hotline to warn one another of sudden security threats, such as North Korean missile launches.

But another plausible answer is more circumspect.

That’s in part because of concerns that a future U.S. president might not be as dogged in supporting and nurturing America’s alliances as Mr. Biden, as Ms. Goto suggests. Many U.S. allies – including in Asia – remain spooked by former President Donald Trump’s disdain for alliances and by the prospect of a return of that perspective to the White House.

But an equal cause for doubts about the trilateral arrangement’s success stem from concerns about the durability of recently blossoming high-level relations between Japan and South Korea.

Despite fits and starts over recent decades at improving relations between Japan and South Korea, the painful history they share – Imperial Japan occupied Korea from 1910 to the end of World War II – has kept resentment of Japan alive in Korea and repeatedly quashed its political leaders’ efforts at rapprochement.

Just two years ago, Japanese and South Korean diplomats refused to take part in a joint press conference at the State Department.

President Yoon is credited by U.S. officials – all the way up to the president – with rekindling efforts at entente with Japan since taking office in May 2022. The Korean leader has gone farther than recent predecessors, agreeing to attend in March the first bilateral summit with Japan in 12 years, and to drop a number of reparations demands related to forced labor during the Japanese occupation.

And now he has embraced the Camp David summit and its objective of building a durable framework for trilateral relations.

Analysts took it as a good sign that President Yoon chose a speech in Seoul last week marking the 78th anniversary of Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule in 1945 to highlight the Camp David summit and a future of closer ties to Japan.

He said the summit would “set a new milestone in trilateral cooperation contributing to peace and prosperity on the Korean Peninsula and in the Indo-Pacific region.”

Prime Minister Kishida also offered soothing words in the lead-up to the summit, saying his country has taken “the lessons of history deeply into our hearts” even as it solidifies its partnerships to deter any adversary threatening to “repeat the devastation of war.”

But are Koreans, and the Japanese, ready to follow their leaders in turning away from the past and focusing on the future?

Perhaps tellingly, Mr. Yoon faced immediate blowback from various sectors of Korean society over his choice of venue for hailing the Camp David summit and its promise of closer trilateral ties – and thus with Japan.

The rapprochement with Japan is generally well-viewed among elites in South Korea, experts note, but less certain is how ready the general public is to move on from the past.

The Yoon Japan policy “is a very top-down approach to diplomatic relations, but what is less certain is whether, at the grassroots level, there is also movement forward on some of these very emotional historical issues,” says Ms. Goto.

“These sensitive wartime grievances may have been shelved, but they haven’t been solved,” she adds, “so it seems the topic will remain a big challenge in any post-Yoon administration.”

The other critical factor in trilateral relations going forward will be China.

China was not even mentioned in the summit’s statement. But that was by design to ease concerns, primarily for the Koreans, that the Camp David initiative not be seen as directed at China – which is the top trading partner for both South Korea and Japan.

Beijing has been vocal in its opposition to tighter relations among the three Camp David partners, insisting they aim to create a “mini-NATO.”

Biden administration officials have insisted that the security framework agreed to by the three countries does not aim to become an alliance on the order of NATO – the security accords the U.S. has bilaterally with each Asian ally are stronger than what the three committed to together, for example. Rather, they say, the Camp David “principles” are about enhancing the expanding economic and military security arrangements the U.S. is pursuing across the Indo-Pacific.

Still, an unconvinced China might only be encouraged to take its own steps to counter the U.S., some analysts say, leading to a buildup of opposing security alliances.

“Whatever the U.S. intent, Beijing will regard Biden’s effort as involving the creation of an East Asian NATO [and] that in turn raises the question of whether Beijing will be deterred or provoked,” says Rajan Menon, director of grand strategy at Defense Priorities, a realist foreign policy think tank in Washington.

One outcome Washington might end up with, he adds, is that “China might increase its military ties with Russia and North Korea.”

How China responds to the Camp David summit concerns all three summit participants, others note, but it remains of particular concern to the two Asian members of the threesome.

“Is China just going to pursue its own military buildup, or will it respond to the security cooperation this summit promises by coming up with a similar diplomatic framework to counter the U.S.?” asks Ms. Goto.

“I wouldn’t say concerns about that put the light of day between the U.S. and the other two when it comes to China, but I do think Washington has to keep in mind the geography,” she adds. “For Japan and South Korea, China is right there. For the U.S., it’s not so close.”