Venezuela is stabilizing. So is Maduro. Too late for new US sanctions?

Loading...

| WASHINGTON

When the numbers came in last month on Venezuela’s oil exports for the last half of 2019, they told two stories.

One was of a national industry operating well below the heyday levels of a half-decade ago, when the country with the world’s largest proven oil reserves was exporting nearly 2 million barrels of crude a day.

But the numbers also told of a modest recovery in exports that has helped buoy the embattled government of President Nicolás Maduro. Indeed, oil exports that had fallen to a dismal 800,000 barrels per day in August – under pressure of U.S. sanctions on the state oil company PDVSA – recovered to 1.1 million barrels per day in December.

Why We Wrote This

With the Trump administration showing signs of ramping up pressures on the Maduro government in Venezuela, doubts about sanctions’ efficacy raise questions about why they’re being relied upon again.

The turnaround in oil sales is just one sign that a government that only months ago had seemed to be on the precipice over a collapsing economy, citizens’ ire over shrinking civil rights and democratic norms, and mounting international pressure, might end up holding on.

President Donald Trump declared a year ago, both in White House meetings and publicly, that Mr. Maduro “has got to go,” and the United States went all in on Venezuela’s young parliamentary leader and self-proclaimed “legitimate” president, Juan Guaidó. But today the Maduro government appears to have stabilized and achieved a new lease on life.

Mr. Maduro’s renewed hold on power could mean the Western Hemisphere has to adjust for the foreseeable future to another authoritarian regime and state-run economy in its midst, some Venezuela experts say. For others, a ramped-up U.S.-led effort to oust Mr. Maduro and return Venezuela to democratic rule can still work, but even they say time is running short.

“Everything suggests that Maduro remains firmly in control – until he’s not,” says Eric Farnsworth, vice president of the Council of the Americas in Washington. Fortunes can change precipitously for despots, he adds, “but for right now, if I’m Mr. Maduro I’m thinking I won. And what that portends for the hemisphere is a de facto second Cuba, but this time with oil.”

More in store from Trump?

Some hold out hope that President Trump will get serious about his “Maduro must go” pledge and order measures beyond sanctions before it’s too late.

“Time is running short for the U.S. to have the impact it wants,” says Roger Noriega, a former assistant secretary of state for Western Hemisphere affairs under President George W. Bush.

Noting that President Trump invited Mr. Guaidó to this year’s State of the Union address, Mr. Noriega, now a visiting fellow on hemispheric affairs at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, says the presidential spotlight “tells me they [in the White House] have elevated Venezuela again.” That and other indications from inside sources “give me reason to believe the administration has more in store that will be coming out in the very near future,” he says.

But Mr. Noriega, who is known as a hard-liner on U.S. intervention in Latin American trouble spots, says Mr. Maduro’s downfall will never come from sanctions and soft-power humanitarian interventions alone.

“If you want to dislodge this regime, you’re going to have to use some kind of force,” he says, conjuring up a past of U.S. military or covert interventions in the region that many analysts deem unlikely today.

But Mr. Noriega says he can imagine the U.S. undertaking what he calls “law enforcement” operations, with allies in the region like Colombia and Brazil, to seal off Venezuela and weaken Mr. Maduro by cutting off revenue sources ranging from oil and gold sales to the illegal drug trade.

“I’ve actually used the word ‘quarantine,’” he says, to describe how he believes the Maduro regime might be brought down.

“Sanctions won’t do it”

For a moment last year it looked like Mr. Maduro was indeed on his way out – for a few hours on April 30 it appeared that the Venezuelan military was switching its allegiance from Mr. Maduro to Mr. Guaidó.

To explain how Mr. Maduro has been able to recover, regional experts cite a combination of a U.S. policy too reliant on sanctions, a disorganized and uninspiring political opposition, and a population worn down by food shortages, repression, and mounting violence.

“The Trump administration has pretty much relied on sanctions to get where it wants to go on Venezuela, but sanctions won’t do it,” says Mr. Farnsworth. “Sanctions are good for raising the costs of certain behavior and for causing pain,” he says, “but I’m not aware of any circumstances where sanctions have led to a change in government.”

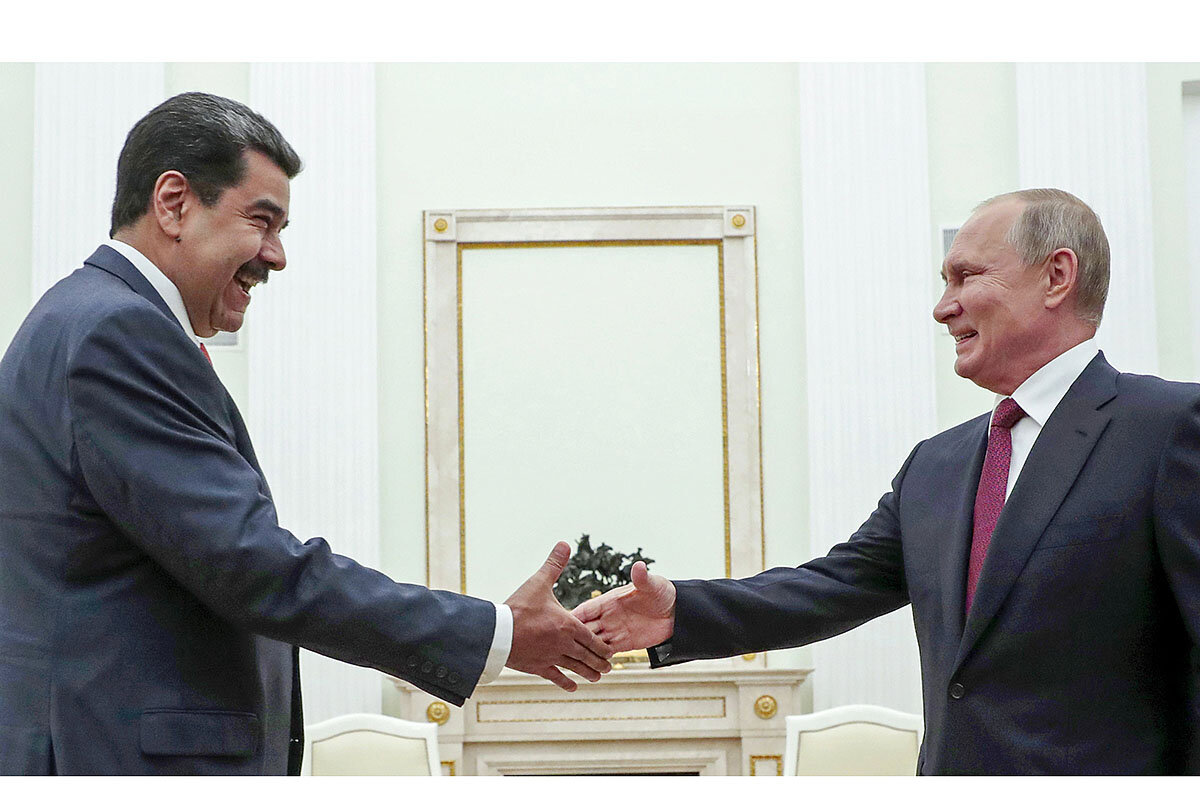

Last week the Trump administration announced new sanctions on a subsidiary of Russia’s Rosneft Oil Company, which has used its trading companies to throw Mr. Maduro a critical lifeline.

In announcing the new measures, a senior administration official told journalists that sanctions slapped on Venezuela so far have reached perhaps “50 to 60 percent” of a full “maximum pressure” effort, and that Venezuela and countries trading with it should expect a further ratcheting up of punitive steps.

But Mr. Noriega says the administration lost precious time relying on sanctions that were never fully enforced – and on a political opposition in Venezuela better known for infighting than for inspiring Venezuelans to action.

“The administration underestimated the regime and overestimated opposition politicians, who were incapable of fomenting an uprising and are better at seeking pacts and phony elections,” he says.

Buying elites’ loyalty

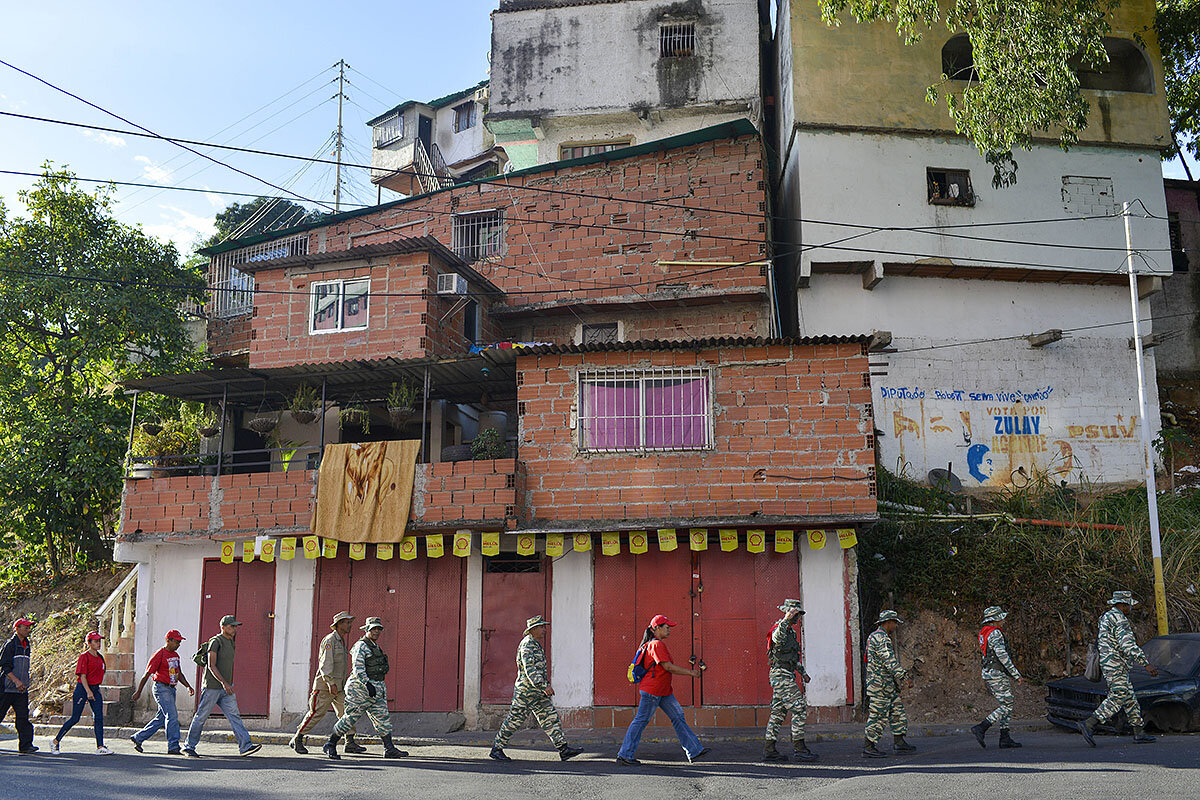

Another key to Mr. Maduro’s improved political prospects is the way he has managed to solidify the loyalty of Venezuela’s elites, especially the upper echelons of the military, through opportunities to build material wealth and live secure lives with international benefits. Most of those “opportunities” involve illicit activities, from siphoning off oil revenues to coordinating gold and narcotics smuggling, some experts note – allowing Mr. Maduro to trade well-being for loyalty.

Some reports estimate the Maduro government has looted $350 billion of Venezuela’s wealth to keep the military and others, including oil industry elites, in line. “Three hundred and fifty billion dollars will buy you a lot of wiggle room if the cadres at the top can muddle through with their AmEx cards and overseas accounts and properties,” Mr. Noriega says.

Despite what looks like new interest in the Trump administration in bringing change to Venezuela, the Council of the Americas’ Mr. Farnsworth says he sees little reason to think things will be much different a year from now.

Average Venezuelans who have decided to stay put – unlike the nearly 5 million, or about 1 in 7 Venezuelans who have already left, creating Latin America’s largest refugee crisis in modern history – will continue to look for ways to scrape by, he says. A new report from the United Nations’ World Food Program this week finds that 1 in 3 Venezuelans live with hunger.

Mr. Noriega warns that the status quo, as dire as it would be for Venezuelans, would also very likely mean worrisome repercussions for regional stability and eventually even U.S. national security.

“This is not just a regime abusing its people, it’s not just an island [like Cuba] that’s going to be a nuisance,” he says. “This is really now a narco-regime that is a pillar of organized crime and of the spreading instability in the Americas.”