Trump team submits UN peacekeeping to scrutiny. Is it a bargain?

Loading...

| United Nations, N.Y.

These days Cote d’Ivoire, Liberia, and Sierra Leone may be stable countries of a quietly advancing West Africa, but two decades ago that was not the case. All three were embroiled in civil conflicts with deep political turmoil and horrendous violence that left no one safe.

Then the United Nations sent in peacekeepers with orders to protect civilians from warring factions – a new mandate that until the 1999 UN mission to Sierra Leone had never been tried before.

No one is likely to claim that the UN’s peacekeeping missions are the only reason West Africa is living much better today. But they were key factors in stabilizing and calming conditions and reversing the downward spiral of violence.

“I feel quite proud of the work we’ve done there,” says Jack Christofides, director of the policy, evaluation, and training division of the UN’s Department of Peacekeeping Operations. “We’re leaving [West African countries] in far better condition than when we went in there.”

Highlighting peacekeeping successes may not be the norm at a time when the focus is more on peacekeeping’s failings – and on pressure for deep reforms in the UN’s biggest and costliest activity. The UN’s new secretary-general, Antonio Guterres, has ordered a full review of peacekeeping operations, and UN peacekeeping’s biggest bankroller, the United States, is also demanding major reform.

But with President Trump calling for large US cuts in its financial contribution to the UN, and with US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley pressing for reforms and undertaking a review of each of the UN’s 16 peacekeeping missions, UN officials and experts in peacekeeping are sounding adamant in response. The Security Council is meeting Thursday to discuss the issue.

Yes, peacekeeping can be improved, the officials and experts say. But the focus should be on reforms that build on peacekeeping’s successes and that help to address the security challenges of the 21st century, they add, not solely on efficiency and cost reduction.

“How to make peacekeeping better and more effective in today’s security challenges is by no means a new topic at the UN, and I think people recognize there’s still potential for a lot of reform,” says Aditi Gorur, an expert in UN peacekeeping and director of the Protecting Civilians in Conflict program at the Henry Stimson Center in Washington.

“The problem is that the drastic cuts Trump has talked about – and that Nikki Haley has done little to deny – create a defensive mentality and a counterproductive environment for the conversation about reform,” Ms. Gorur says. “So while [Ambassador] Haley is taking office in an atmosphere that is welcoming of US goals, there are also fears that the priority will be on cutbacks over doing things better.”

Dramatic change in mission

The Trump administration may be talking about cost cuts, but many officials and international security experts see UN peacekeeping as one of the world’s great bargains.

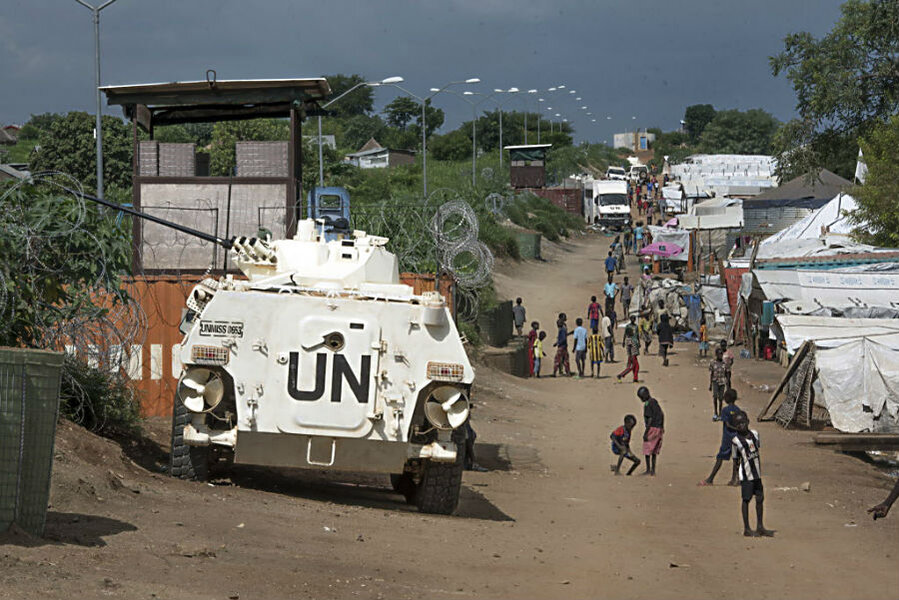

Currently about 100,000 peacekeepers, most of them provided by developing countries, are deployed in the 16 missions – concentrated in Africa and the Middle East – at a cost of about $8 billion a year. That’s about 1 percent of global annual outlays on defense and military spending, experts note.

The US pays 28 percent of the annual cost – Trump wants to lower the US share to 25 percent – or about $2.2 billion. That’s roughly the price tag on two B-52 bombers, peacekeeping’s advocates like to point out.

Peacekeeping missions are authorized by the UN Security Council – and those missions have evolved markedly as global security threats have changed and the international community has assumed new responsibilities, such as protection of civilians caught up in civil wars or political strife.

The end of the cold war is the line of demarcation between old and new peacekeeping, with missions before about 1990 largely deployed to monitor cease-fires in international disputes, from Kashmir (separating Indian and Pakistani forces) to the Golan Heights (between Israel and Syria).

The 1990s saw the first of what would become the post-cold-war norm: missions deployed to civil conflicts.

That decade also witnessed peacekeeping’s first big failures – in Rwanda, Somalia, and Bosnia – when mission mandates did not yet include the goal of protecting civilians.

Peacekeeping grew dramatically in the 2000s, as civil and often ethnic-driven conflicts spread across Africa, and the Security Council increasingly included protection of civilians in the mandates of new missions. The UN peacekeeping tab roughly doubled in the decade after 2004 – from $4 billion to today’s $8 billion – starting under the presidency of George W. Bush and extending into that of Barack Obama.

Reforms should build on successes

But the rapid expansion led to new problems, with the deployed “blue helmets” – as UN peacekeepers are known – often ill-equipped to operate in the complexities of civil conflicts. The new era’s biggest disappointments include repeated cases of peacekeepers’ sexual abuse of the women and minors they were deployed to protect, and the Haiti mission’s introduction of cholera to the Western Hemisphere’s poorest country.

Despite those black eyes, peacekeeping’s proponents say the good far outweighs the bad – and that reform efforts must start from that basis.

UN officials say that for every mistake and embarrassment peacekeepers have committed, there are many more cases of protecting large numbers of civilians, freeing child soldiers, even heading off genocides.

The Stimson Center’s Gorur says peacekeeping can do better, and that the reform effort should focus on improvements such as establishing missions with “a vision and a clear idea of what the endgame is,” and “benchmarks” for determining a mission’s progress and success – elements she says have been missing.

Indeed “protecting people better” is also what Ambassador Haley says the US wants peacekeeping to do, if more efficiently.

At a press conference in New York Monday, Haley said the US was finding strong support among its UN colleagues for the peacekeeping reform effort. “There is strong consensus in the Security Council that we need to move forward” with reform, she said.

“The goal is to be effective … protecting people on the ground,” she said, “We need to make sure we’re changing with the times.”

The case of the Congo mission

The initial test case of where the US intends to go with its reform effort was the mission to the Democratic Republic of the Congo – which at around 17,000 peacekeepers is the UN’s largest.

Haley blasted the Congo mission last month as a support for a “corrupt” government “inflicting predatory behavior against its own people,” and she admonished the Security Council to “have the decency and common sense to stop this.”

That alarmed other council members, including France, who insisted that the peacekeepers are protecting civilians from all of Congo’s armed actors, and that ending the mission now would invite disaster.

By Friday, when the Congo mission came up for reauthorization, the US was on board with a plan cutting the mission by only hundreds of peacekeepers, to 16,000. Still, Haley celebrated the renewed mission as “the start of peacekeeping reform,” and said it would save millions of dollars.

That outcome heartened peacekeeping advocates who took it as a signal that “reform” was not going to be a euphemism for thoughtless downsizing and cost-cutting.

“I don’t think the US has any intention to slash and burn peacekeeping,” one senior UN peacekeeping official says. “We want to make changes – our only proviso is that whether adjustments are made needs to be based on political and security realities.

"When you have another agenda,” he adds, “you’re running into trouble.”