Why the airline 'electronics ban' may not be discrimination

Loading...

The United States and British governments' "electronics ban" prompted quick comparisons to the Trump administration’s much-criticized bans on travel from Muslim-majority countries, with one former US official telling Buzzfeed News that, “It appears to be a Muslim ban by a thousand cuts.”

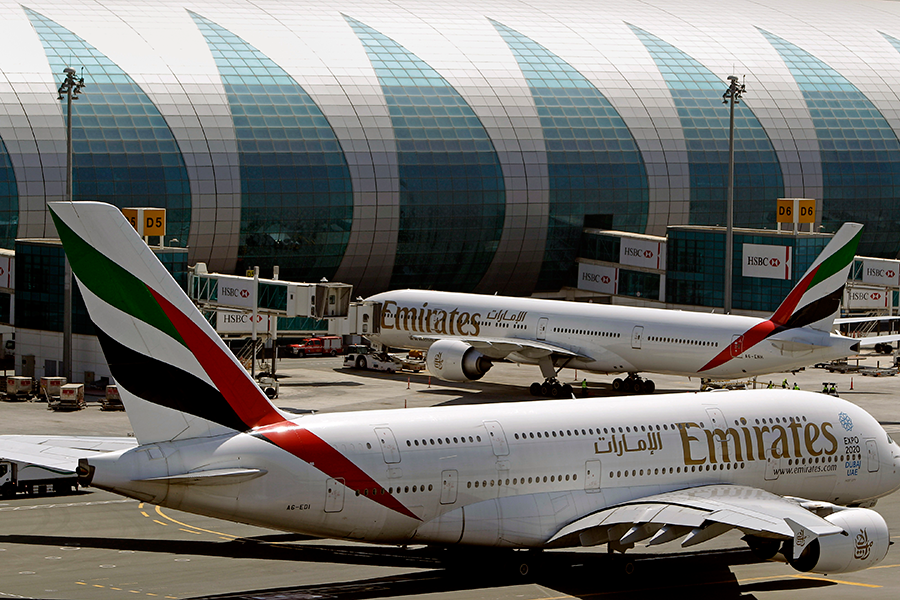

While the policy's timing and targeted locations have raised eyebrows, the scholars who study terrorism aren't quite ready to equate the new policy – which bans any electronics larger than a cellphone from being carried on flights departing from 10 Middle Eastern airports – with discrimination.

These security experts point to a need for greater transparency. But they also suggest taking a broader perspective. In their view, the "electronics ban" is consistent with how the US government has handled previous terrorist threats, and it may not stem from prejudice toward Muslims.

“I think to immediately jump to the conclusion that this is connected with the travel ban is too far, too quick,” says Robert Pape, professor of political science at the University of Chicago who specializes in international security. This latest ban “has the hallmarks of our airport security system responding to new information about an immediate threat,” he explains in a phone interview with The Christian Science Monitor.

A similar response came in August 2006, he continues, when British authorities learned that an Al-Qaeda cell was planning to detonate liquid-based bombs on airliners headed for the US and Canada. Authorities responded by banning almost all liquids on flights leaving Britain. The US has since instituted a ban on containers of liquid larger than 3.4 ounces.

America's Transportation Security Administration has also long told flyers to take their laptops out of their cases when sending them through an airport X-ray. Jeffrey Price, professor of Aerospace Management at Metropolitan State University of Denver, tells the Monitor in an email that he was asked to turn his on before a recent flight out of Charlotte, N.C. "It happens from time to time when TSA either is doing random checks, or has received intelligence that someone may attempt to bomb an aircraft using an electronic device as a detonator."

That's for a good reason, says Sheldon Jacobson, a professor of computer science at the University of Illinois. “The shell of a laptop or some kind of sophisticated iPad could potentially contain explosives which could bring down an airplane,” he tells the Monitor. Last February, Al-Shabaab terrorists in Somalia nearly accomplished just that, using a laptop bomb to blow a hole in a passenger jet; only the plane’s low altitude saved it from destruction.

Detonating a bomb manually “is also more straightforward” than using a timer, adds Professor Jacobson, an expert on airline security. “So that is a credible threat.”

Given all these circumstances, Dr. Pape, who directs the Chicago Project on Security and Threats, suggests that there is likely “intelligence that is actionable that has come into our Department of Homeland Security, and that what we're doing is reacting to it.”

But Pape also has questions about how the feds are reacting. “There's two things that are odd about this. Number one, the [96-hour] delay in the prohibition. Number two, having the prohibition apply to a subset of countries and airports.”

Both could make it easier for a terrorist to slip through. Giving the airlines four days to comply – rather than requiring flyers to check their devices immediately – means that “the bad guys could speed up their timetable” for an attack. He says that’s what Aum Shinrikyo, a Japanese doomsday cult, did with their 1995 sarin gas attack on a Tokyo subway. “We do have cases of terrorist groups speeding up their timetable once they know the authorities know.”

Pape also questions why the directive focuses just on those 10 airports. One facility on the list, Istanbul’s Atatürk airport, did suffer a high-profile attack last summer, but at the terminal building rather than on the planes.

Analysts have raised concerns about the lax security in some countries’ airports, but Pape doesn’t see the ones listed as falling below US standards. “I've been through some of these airports, these are not [places with] Keystone Cop-level security,” referring to fictional, bungling police officers portrayed in early 20th-century silent films. “They unpack your bags and search you pretty thoroughly.”

For his part, Professor Jacobson cautions that would-be terrorists can simply travel through unaffected airports. With a ban that only targets the carry-on laptops, cameras, and tablets at ten international airports, terrorists would “simply fly to Western Europe, where such a ban is not being enforced, and from Western Europe, they would fly to the United States. So it is very easy to circumvent this ban.”

“I cannot logically connect the dots, based on my knowledge of aviation security, that this will actually affect any kind of improvement in security.”

Absent more explanation, the selection of ten airports in Muslim-majority countries is inviting comparisons to Trump's controversial travel ban. “The administration hasn’t provided a security rationale that makes sense for this measure targeting travelers from Muslim-majority countries,” Hina Shamsi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Security Project, tells the Monitor in an email. “Given the administration’s already poor track record, this measure sends another signal of discriminatory targeting.”

That motive is “possible,” Pape says. “I wouldn't rule it out completely.” But he suggests that the “security rationale” for the ban should be the public’s main focus. In particular, he wants answers to what he calls “the two puzzles:” the 96-hour delay and the selection of airports.

“We need to lay out what the two puzzles are crystal-clearly, and encourage the administration to explain those puzzles, and encourage those members of Congress charged with oversight in the House and Senate Intelligence committees to ask those questions as well.”

“That's really the future here. These [answers] are what we need to pursue.”