How to prevent ISIS from getting dirty bomb? Russia and US need to talk.

Loading...

| Washington

Some of the best minds on nuclear nonproliferation on Tuesday considered a chilling prospect: What if the Paris attackers had had a dirty bomb?

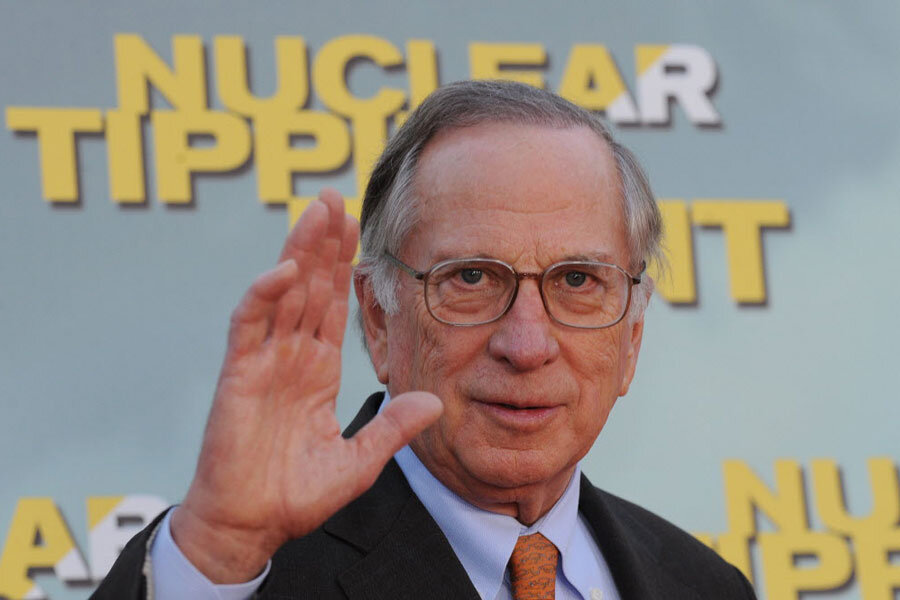

To prevent that scenario, the international community urgently needs to come together to safeguard against both the spread of nuclear and “radiological” materials and illicit access to them, says former Georgia Sen. Sam Nunn.

In particular, that means a return to sustained and fruitful dialogue for two countries that don’t currently seem to have much use for one another: the United States and Russia.

“To use dialogue as a bargaining chip between the two countries that have 90 percent of the nuclear weapons and 90 percent of the nuclear materials in the world makes no sense from a strategy point of view,” says Mr. Nunn, co-chairman of the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI).

Nunn says he doesn’t paint horrific scenarios simply to frighten people, but rather to convey the urgency of the task at hand.

“A dirty bomb made with cesium-137,” a radioactive isotope produced for use in common medical devices, could cause more widespread loss of life “and deny access in areas of large cities where the weapon exploded for 30 to 40 years,” Nunn says. “And ISIS has claimed they have that kind of material.”

Nunn was part of a gathering of American and Russian arms-control experts in Washington Tuesday, where the consensus view on keeping weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) out of the hands of terrorists echoed the former senator: Revived and expanded US-Russia cooperation will be key.

“In the context of noncooperation [between the US and Russia], the potential for terrorist organizations getting access to nuclear materials and even nuclear weapons is on the rise sharply,” says Alexei Arbatov, a nuclear weapons expert with the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow and a deputy chairman of the International Luxembourg Forum on Preventing Nuclear Catastrophe, which organized the conference with NTI.

A more conventional view might be that terrorist groups seeking WMDs and related materials would be more likely to turn to non-state actors – for example, crime gangs – to gain access to controlled materials. WMD experts acknowledge that this avenue poses a problem.

But they also point to the bilateral efforts by the US and Russia to rid Syria of most of its chemical weapons stockpile – an experience they say illustrates how cooperation between powers otherwise at loggerheads with each other can pay big dividends.

It was former Indiana Sen. Richard Lugar who first came up with the idea of the US and Russia working together to devise a plan to destroy Syria’s chemical weapons, Nunn said – telling journalists of comments made by Andrew Weber, a former assistant secretary of Defense for nuclear, chemical, and biological defense programs. A year before the August 2011 crisis over Syria’s chemical weapons use, Senator Lugar and Mr. Weber met repeatedly with Russian colleagues to discuss the issue and formulate how a chemical weapons destruction plan would be carried out.

Because of that in-depth and high-level cooperation “a plan was on the shelf for the leaders [of the two countries] to take a look at” when the issue of Syria’s [chemical weapon] stockpile was about to explode, Nunn said. “Perhaps there might not have been an agreement if those discussions hadn’t taken place beforehand.”

Other key steps should be taken to bar terrorist access to WMDs and related materials, experts say, including:

- Stepped-up assistance to less-developed countries to enhance controls on nuclear and radiological materials;

- Closer military-to-military cooperation and intelligence community information-sharing on the Islamic State, Al Qaeda, and other terrorist groups posing a global threat;

- Measures to ensure that the same illicit networks that provided the Islamic State terrorists with illegal weapons in Europe don’t also end up as suppliers of WMD materials.

All of these measures are important, but none will advance in any significant way without a return to closer cooperation between the US and Russia, says Mr. Arbatov.

“Everything is at a stalemate, for example there is no longer [US-Russia] cooperation on the safety of fissile materials,” he says. “That is not the way to prevent nuclear weapons from ending up in the hands of the terrorists.”