US 'pivot to Asia': Is John Kerry retooling it?

Loading...

| Washington

When John Kerry spoke at his confirmation hearing to become secretary of State, Asia experts took notice when he seemed to back away from a key aspect of President Obama's vaunted "pivot" to Asia.

"I'm not convinced that increased military ramp-up [in the Asia-Pacific] is critical yet," Mr. Kerry said at the January hearing. "That's something I'd want to look at very carefully."

The "rebalancing" of America's focus and resources – away from the Middle East and toward a rising Asia – was considered part of the legacy of Kerry's predecessor, Hillary Rodham Clinton. China had been put on notice that the United States was reasserting itself as an Asia-Pacific power. But was Kerry suggesting, as some surmised, that the US would now focus more on engagement with a rising China? Was he signaling that the "pivot to Asia" is no longer a guiding priority?

Or, as a senior State Department official suggests, was Kerry simply saying that the US, which has played a key role in Asia's security and prosperity for decades, will be cautious not to do anything that might jostle the region? "Anything that could upset [what we've helped accomplish in Asia] has to be looked at very carefully" – including a potentially unsettling military buildup, says the official, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Whether the Asia pivot is "real or rhetoric" will be answered in the coming months, regional analysts say – as the US addresses the simmering territorial disputes in the seas of Southeast Asia, as it signals the diplomatic attention it intends to give the region, and as it moves ahead, or not, on an ambitious regional trade pact called the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

For US officials, the pivot never meant turning toward something new, since the US has been a Pacific power for more than a century. Rather, they describe it as "refocusing" on the world's most economically dynamic region. And they say the US is taking concrete steps to make the pivot a reality.

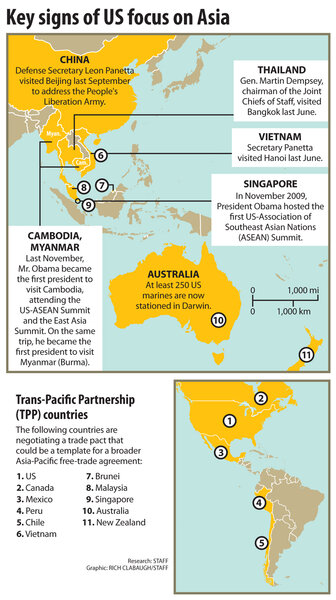

In November 2011, Mr. Obama announced plans for up to 2,500 US Marines to be stationed in Australia – a first for the US. And by 2020, 60 percent of the US naval fleet will be deployed to the Asia-Pacific, Defense Secretary Leon Panetta announced last June.

On the diplomatic front, Mrs. Clinton pressed ahead with building up "institutional architecture" for US-China relations, establishing regular high-level meetings.

She also ramped up US involvement elsewhere in the region, particularly with Southeast Asia – a strategic focus for both the US and China. Clinton made a point of attending forums of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) every year of her tenure – a first for a secretary of State.

In addition, Obama had the US join a new grouping – the East Asia Summit (EAS) – and he attended the summit two years in a row. Obama also hosted the first US-ASEAN Summit, held in Singapore in 2009, and then attended annual ASEAN summits, as well as Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summits.

This bump-up of attention to the region by the US president does not go unnoticed by leaders, says Michael Green, a senior Asia adviser in the George W. Bush administration who is now at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

"The president's commitment to the EAS may be the most lasting dimension of the pivot," he says.

For some US diplomats, a crucial factor in making the pivot more than rhetoric is the number of largely unseen working groups and other contacts being established on issues that range from trade and investment to e-trade security. Their goal is to boost the region's prosperity while making the US an integral part of it.

So far, the "ramp-up" in economic contacts has largely been accomplished by "juggling" existing resources, but requests in the 2014 budget are based in part on adding new "slots" in both Washington and the region, the senior State Department official says.

"We are taking advantage of revenues that will be somewhat freed up" by the "rebalancing" of resources from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the official says.

Yet despite this evidence of a redirection, it remains unclear if what began in Obama's first term will carry over full force into his second, many regional analysts say. "Clearly the meaning of the pivot a year and a half ago is different from its meaning today," says Dean Cheng, a research fellow at The Heritage Foundation's Asian Studies Center in Washington.

"Secretary Kerry seemed to be saying in his confirmation statement [that] we don't need a pivot," he adds. "We'll see in the months ahead if the political and military and economic attention we give the Asia-Pacific region confirms that that's what he meant."

One significant question, Mr. Green says, is the defense budget – whether cuts can be made while keeping the envisioned redeployment of forces to the Asia-Pacific.

Another important indication of where the pivot is headed will come when Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe travels to the White House Feb. 22.

Mr. Abe – who has made no secret since his election in December of the priority he places on revitalizing relations with the US – visits as a territorial dispute between Japan and China over a collection of uninhabited islets (the Senkaku, or Diaoyu) heats up.

How far Obama goes in supporting Japan, with whom the US has a security treaty, will say a lot about how the US wants China to interpret its role in the region, some say.

But other signals out of the White House will be just as important, regional analysts say – such as who makes up the administration's Asia team. Asia analysts want to see who replaces Kurt Campbell, the recently departed assistant secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, who worked closely with Clinton to move the Asia pivot beyond rhetoric.

The region will be watching, too. "In the Chinese view, the pivot was identified with Mrs. Clinton," says Mr. Cheng of Heritage. "Her departure and that of Kurt Campbell will be seen as a weakening, a diluting of the pivot."

Another indicator will be what happens this year with the TPP, a new trade group being negotiated by 11 Pacific Rim countries, including the US. Negotiators have set a deadline of September for reaching an accord, which many say could serve as a template for extending trade agreements across the region.