Syria: Has Obama done enough to bring the violence to an end?

Loading...

| Washington

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has agreed to a new “approach” to end his country’s violence, UN special envoy Kofi Annan said Monday, adding that he would soon take the proposal to Syria’s armed opposition.

But with President Assad insisting to international media that he will accept no deal that includes his departure from power, and with the opposition adamantly opposed to any plan that includes Assad, Mr. Annan’s undisclosed breakthrough appears to be just as dead as his three-month-old six-point plan – which, he acknowledged over the weekend, “has failed.”

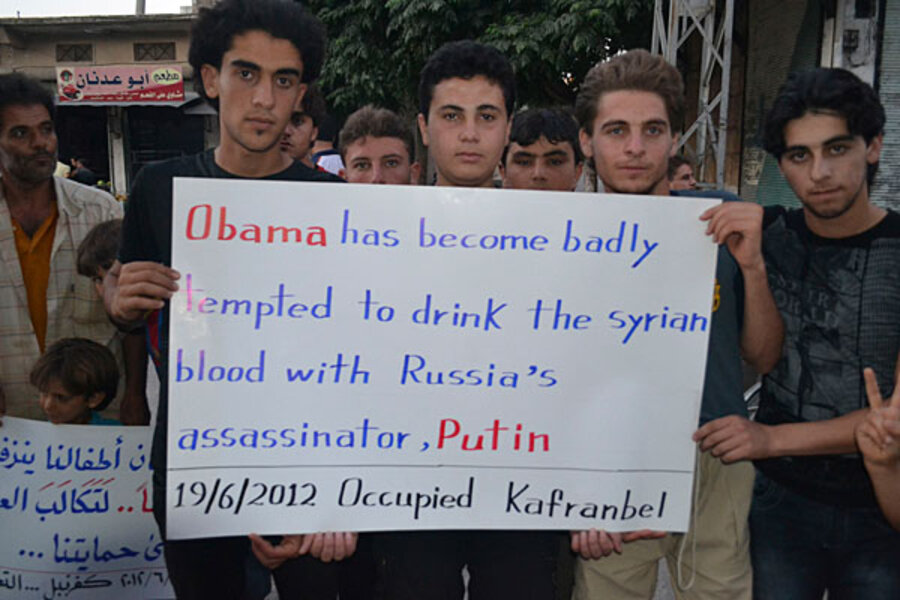

The failure of international diplomacy to address Syria’s grinding violence – some 14,000 Syrians have died in 16 months of turmoil, according to unofficial estimates, with about 6,000 of those deaths occurring since Annan proposed his peace plan in April – is feeding renewed criticism of the Obama administration’s Syria policy.

But even harsh critics who advocate more robust involvement by the United States say they don’t expect to see direct American intervention any time soon.

“It’s not a very good or effective policy, but I sense [the administration] will be able to maintain it until the [US presidential] election,” says Elliott Abrams, who served in diplomatic roles in the George W. Bush and Reagan administrations.

Mr. Abrams, now a Middle East analyst at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington, says the Obama administration’s “do-nothing policy” on Syria will be to blame when perhaps as many as 20,000 Syrians die before Assad finally falls.

But he also acknowledges that the Syrian opposition’s growing effectiveness is, in a way, making it easier for the administration to put off hard choices such as directly arming the rebels – which Abrams favors.

“If you look at their performance on July 9 and compare it to April 9, there’s obviously been improvement,” Abrams says. The rebels’ better performance suggests they are getting arms and other equipment from somewhere, he says. “But with things looking like they’re going fairly well for the opposition,” he adds, “that reduces the pressure on the administration.”

But others say a combination of Annan’s inability to make a peace plan stick and Syria’s continuing violence is forcing the administration to ratchet up the indirect intervention it opted for as the Syrian crisis intensified.

“Somewhere along the line this [administration] decided it was going with indirect intervention – the political warfare we’re seeing, encouraging the opposition, the signs of some form of support on the ground – and that’s what is building up here,” says Jeffrey White, a defense fellow specializing in the Middle East at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Mr. White favors the “direct intervention” by a coalition of the willing – including the United States – as the way to end Syria’s crisis the most rapidly and with what he says would be the least amount of bloodshed and material damage to the country. But he adds that while he sees little sign of pressure building on the administration to switch to “direct intervention,” he does believe pressure for what he calls “second-best” indirect intervention is growing.

As a result, he says, the administration is stepping up what he calls “political warfare” – for example, calling publicly for the Syrian military to abandon Assad, and warning those officers who don’t of “consequences” (such as an international tribunal) down the road once Assad is out of power.

White says “something happened” in or about May that initiated a noticeable improvement in the performance of the opposition forces. That growing effectiveness has led to speculation that the US and other Western powers are indeed arming the opposition, even though the administration maintains that the US is only providing some communications equipment and working to ensure that the arms that are being provided by some of Syria’s neighbors are not falling in the hands of Al Qaeda-affiliated terrorists.

Abrams says he hopes the US is doing more for the opposition than it is claiming publicly, if only for the role the US will want to play in a post-Assad Syria.

“If it’s the Saudis and the Qataris giving money and guns to the opposition, then it’s the Saudis and Qataris who are going to have influence when that opposition is in power,” he says, “and the US won’t have the influence it could’ve had.”