Could Al Qaeda get Syria's chemical weapons?

Loading...

| Washington

Add to the list of worries about an extended and deepening conflict in Syria the potential threat posed by the government’s stockpiles of chemical and other mass-destruction weapons.

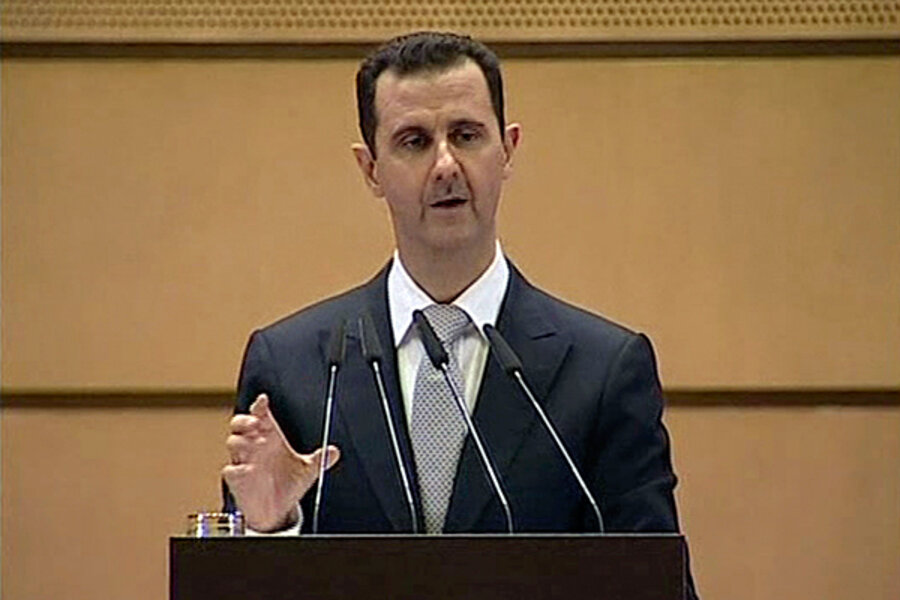

Mounting defections by Syrian security forces and recent bombings of government buildings are among the factors behind growing concerns that the regime of President Bashar al-Assad could lose control of what are thought to be substantial weapons holdings.

Syria is thought to have large caches of nerve and mustard gases, plus thousands of shoulder-fired missiles – weapons that the Israelis, Jordanians, Turks, and other neighbors worry could fall into the hands of Al Qaeda and other terrorist groups.

“We know they have a lot of nerve agents, blister agents, persistent and nonpersistent gases, and they’ve weaponized them for battlefield use,” says Jeffrey White, a defense affairs fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. “It’s a very big problem.”

The concerns are reminiscent of those that the United States and other governments expressed about Libya last year as Muammar Qaddafi lost control of the country’s security installations and weapons depots. Worries over the potential ramifications of loose weapons, including shoulder-fired missiles, were serious enough to prompt the US to put up $40 million to track down and destroy Libya’s weapons.

But as daunting as the task of finding and destroying Libya’s arms continues to be, US officials say Syria poses a bigger threat.

The Syria situation is “much more difficult,” Thomas Countryman, assistant secretary of State for international security and nonproliferation, told reporters this week – for reasons ranging from lack of knowledge about Syria’s weapons stockpiles to the complexity of the region surrounding Syria.

Officials in neighboring Israel have already expressed concerns about the implications of any “loose” portable antiaircraft missiles on the operations of Israel’s Air Force. Others note that Syria possesses Scud missiles that could be employed to carry chemical weapons into neighboring countries.

“Syria’s a much bigger problem. Libya was small potatoes by comparison, and we had a pretty good idea of what they had and where they had it,” Mr. White says. “But Syria has gone to great effort to hide what it has, especially with its enemy Israel right next door, and it probably has many times more chemical weapons.”

US officials worry that Al Qaeda may be stepping up an infiltration of Syria from neighboring Iraq and could take advantage of a power vacuum that could result from an Assad collapse. Recent bombings that struck Syrian security and intelligence targets look to be Al Qaeda’s handiwork, US officials say.

In Senate testimony Thursday, Director of National Intelligence James Clapper said the recent bombings in Damascus and Aleppo carry “all the earmarks of an Al Qaeda-like attack.” He also underscored the potential threat that Syria’s chemical weapons could pose, were they to fall into the wrong hands.

The US is using satellites and other technology to try to keep track of Syria’s weapons sites and to watch for any signs of weakened security. But says White, who spent years in the Defense Intelligence Agency, “It’s doubtful we have an all-seeing eye on what’s going on” concerning Syria’s weapons stockpiles.

US officials say they have no indications that the Assad government is either dropping its guard of weapons stockpiles or contemplating using any mass-destruction weapons. While that may be true, it leaves the problem of a large but deteriorating army, White says.

“The bigger problem right now is that [some of these weapons] might be stored with battlefield units that are in some areas of rising instability,” or with units that are experiencing rising numbers of defections, he says. “That could open the way to some of these weapons getting loose.”