An accelerating covert war with Iran: Could it spiral into military action?

Loading...

| Washington

When a sophisticated American spy drone went missing a month ago and fell into the Iranian military's hands, what had been whispered speculation at the end of the Bush administration became an all-but-officially acknowledged conclusion: The United States, along with a few key allies, is involved in an accelerating covert war with Iran.

It's an example of what some are calling "21st-century warfare," given the deployment of cyberworms instead of soldiers and mysterious explosions at key military installations instead of aerial bombardment.

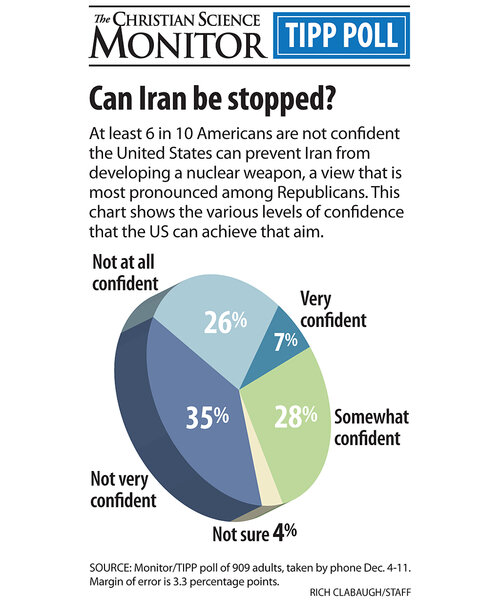

The overarching goal is to slow, if not reverse, Iran's apparent progress toward developing a nuclear bomb – something international diplomacy and a series of economic sanctions have not been able to accomplish. The measures also appear designed to put off the need for a military attack to stop Iran from joining the nuclear club.

The US, Israel, and Britain are thought to be involved in this unacknowledged war. While many actions go unclaimed, the intensification is occurring as the Obama administration signals a hardening stance toward Tehran.

An on again, off again war for 30 years

"We've been intermittently fighting a cold war with Iran for three decades, and the covert aspect of it has increased substantially in the last few years," says Karim Sadjadpour, an Iran analyst at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington. "Both President Bush and President Obama seemed to calculate that covert means can be effective in delaying Iran's nuclear progress, and at a fraction of the political and economic costs of a military attack."

Yet as incidents in an intensifying cold war multiply, with Iran appearing to ratchet up its response, more experts and former intelligence officers who specialize in Iran are cautioning that a spiraling tit-for-tat covert war risks becoming a hot conflict.

"I'm skeptical about any meaningful impact these kinds of actions have, except perhaps the significant effect of making the people involved more hard-line and determined than they were before," says Matthew Bunn, a nuclear proliferation expert at Harvard University's Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs in Cambridge, Mass. "It's hard to see how this kind of covert activity is really going to change anything, except for the worse."

Add to the mix the rising political temperature in the US, with Republican presidential candidates trying to outdo one another on how much tougher they would be on Iran than Mr. Obama. Some Iran analysts warn of increased opportunities for "miscalculations" that could result in a potentially costly showdown.

"The kinds of covert actions we're seeing now are all double-edged swords," says Barbara Slavin, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council's South Asia Center in Washington, "because if something goes wrong you could be in an overt war situation."

With the administration under political pressure and sounding increasingly hawkish about Iran, she adds, "The trick will now be getting to November without a war."

Tensions with Iran heightened this week, although not because of covert activity. Rather, the US is close to enacting sanctions that would target Iran’s oil revenue – and Iran has responded by threatening to close the Strait of Hormuz, through which a sixth of the world’s oil flows. However, the US has a plan to keep the strait open, according to a New York Times report.

In recent months, tensions have also heightened with a string of mysterious and unclaimed activities in Iran. The recent drone incident was the latest of those activities.

Other incidents have included the use of computer worms to attack Iran's nuclear installations, including the Stuxnet virus that in 2010 was thought to have destroyed more than a thousand of Iran's uranium-enriching centrifuges by causing them to spin out of control. Several Iranian nuclear scientists have been assassinated, and in November explosions ripped through the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps' ballistic missile base near Tehran. Seventeen people were killed, including one of the IRGC's top officers in the missile development program.

In October, the Obama administration accused Iran of plotting to assassinate the Saudi ambassador to Washington, an alleged plot that some Iran analysts see as an Iranian effort to hit back. The storming of Britain's Embassy in Tehran in late November and a December explosion outside Britain's Embassy in Bahrain may be other signals of Iran's intention to respond to covert fire.

Yet if the covert activity is designed to slow Iran's nuclear progress, many doubt it will work. As damaging as Stuxnet may have been, it did not curtail Iran's enrichment activity permanently, experts say. And Iran is thought to have many more nuclear scientists and missile designers than Western intelligence services could ever eliminate.

"These programs involve dozens and hundreds of people, so taking out five or 10 is not going to do that much," says Mr. Bunn of Harvard. "If some clandestine force had taken out Gen. [Leslie] Groves in the Manhattan Project, would they have found some other hard-charging officer to lead the project and deliver the bomb? Probably."

On the other hand, covert action like assassinations can slow a regime's progress toward its aims, Bunn says – for example, by sowing doubt about who within a program may be working for "the other side."

Does Iran seek confrontation with West?

Some point to Israel's bombing of Iraq's Osirak reactor in 1981 as evidence that covert activity does not necessarily provide a means of avoiding military action – and may even make it more likely. Iraqi nuclear scientists had been targeted by unknown assailants (assumed to be Israeli operatives), but that did not prevent the airstrike. Research in the years since the attack has largely concluded that while the strike destroyed Osirak, it also prompted Saddam Hussein to push his weapons programs farther underground.

Iran might even welcome a military confrontation with the West – especially one that strikes its nuclear installations, a source of much national pride. "There is a legitimate concern that Iran may seek to provoke a military conflagration," says Mr. Sadjadpour at the Carnegie Endowment, "in order to try and mend its internal political fissures, both between political elites and between the society and the regime."

But even some Israeli military experts say that bombing Iran's nuclear installations would at best only put off its race for the bomb – and might harden its determination to build a weapon it claims it isn't developing.

As Sadjadpour says, "If Iran continues to put all of its political will and vast economic resources behind its nuclear weapons capability, or a nuclear weapon itself, we can at best delay them."

• Material from the Associated Press was used in this report.