Will Fukushima crisis chill civilian nuclear energy deals?

Loading...

| Washington

A year after President Obama’s landmark nuclear security summit brought dozens of world leaders to Washington, global powers are making progress at locking down unsecured nuclear materials, some experts say.

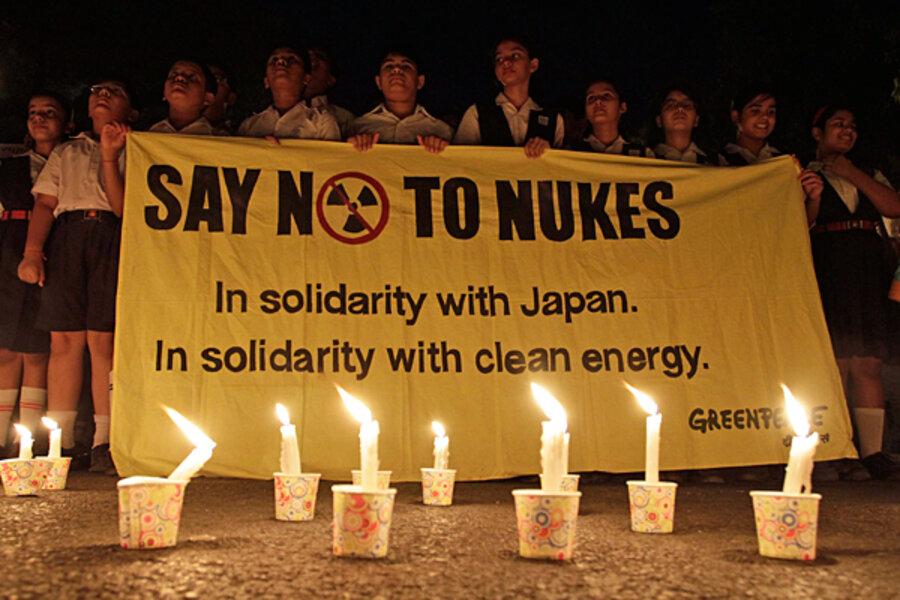

But at the same time, others caution that the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan should put the world – including the United States – on notice about the dangers of spreading nuclear energy technology around the globe.

“We’re going to have a pause in the growth and expansion [of nuclear power] of a decade at least” as a result of the Japanese nuclear accidents, says Henry Sokolski, executive director of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center (NPEC) in Washington. “This pause is something that people who want to keep open the nuclear power option have to use to address the very real safety issues,” he says.

Top 10 most nuclear-dependent nations

The US is in varying degrees of discussion with a number of developing countries – ranging from Jordan and Vietnam to Saudi Arabia – on agreements that would open the way for those countries to acquire a civilian nuclear-power-generation capability.

Perhaps the best-known such civilian nuclear power agreement is the one the Bush administration negotiated with India. That accord is seen to have paved the way for a new era of US-India relations – suggesting the geopolitical ramifications of what is essentially an economic agreement.

But Mr. Sokolski, a harsh critic of the civilian nuclear agreements, says that while those agreements pose significant safety issues, an even more pressing security concern is that of the proliferation of nuclear technology and fuels.

“Can we spread nuclear power locally without spreading the bomb? No,” he said in a presentation on Capitol Hill Monday to congressional staffers. “We skirt the [proliferation] issue by focusing on economics and safety.”

Improvement on 'loose nukes'

The global picture concerning existing unsecured nuclear materials – so-called loose nukes – appears to be brighter. A new report issued Monday to mark the first anniversary of the nuclear security summit finds that many of the commitments signed onto by the 47 countries that attended have already been fulfilled.

According to the study by the Fissile Materials Working Group (FMWG) – an international coalition of nuclear security experts – nearly two-thirds of the national commitments have been completed, while “notable progress” has been made on another 30 percent of them.

Still, the group, which is marking the one-year point at a meeting this week in Vienna, says the task now is to begin setting the next round of goals for nuclear materials security that should be agreed upon at a second summit in Seoul next year.

“The follow-on summit in Seoul needs to move the ball significantly forward by endorsing new initiatives that expand the nuclear materials security regime’s current limits,” says Kenneth Luongo, co-chair of the FMWG and president of the Partnership for Global Security in Washington. “We do not want to see a nuclear terrorist version of Fukushima.”

Some nuclear security experts say that if even more progress isn’t made in “locking down” vulnerable nuclear materials around the world, part of the blame can be assigned to Congress for failing to fully fund US participation in bilateral and international programs for securing nuclear materials.

On the other hand, Congress has been instrumental in toughening the civilian nuclear energy cooperation agreements – so-called 123 agreements – that administrations have signed with foreign governments.

US has more stringent requirements

Some proponents of the agreements note that the United States has more stringent requirements in its bilateral accords – for example, obtaining commitments that nuclear fuels are not converted for noncivilian purposes – than do other nuclear powers selling civilian nuclear technology. (In a controversial move China, which does not make the same demands on its clients, recently agreed to sell new nuclear reactors to Pakistan).

The NPEC’s Sokolski says the US should use what he predicts will be a “pause” in nuclear power agreements after Fukushima to press for greater agreement among the world’s nuclear suppliers on tougher standards for all countries to follow in sharing – really agreeing to sell – nuclear-power-generation equipment.

“I don’t know what’s possible,” he says, noting that the odds of forging an agreement with China “are not great.” Still, he says, “We should at least be in the business of trying, and we’re not.”