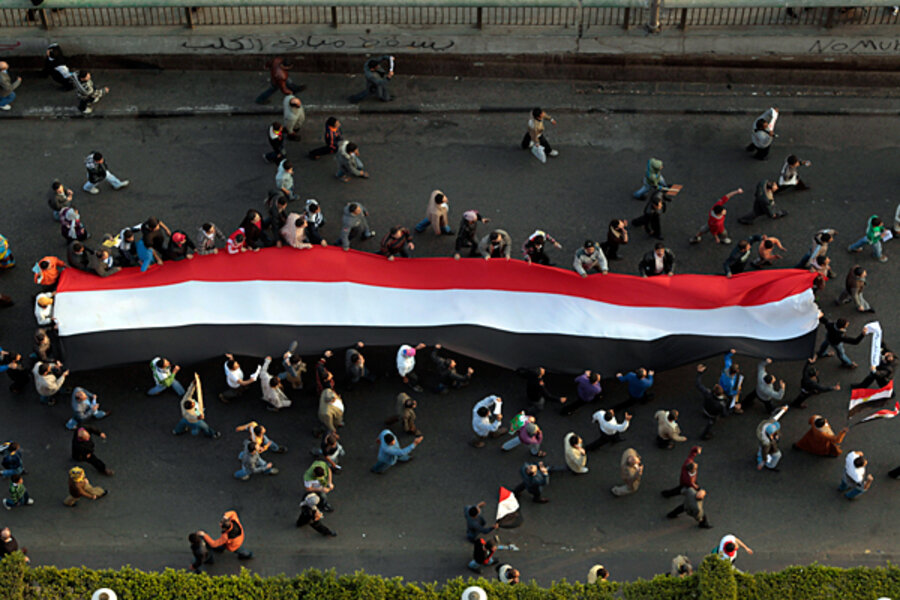

Democracy uprising in Egypt: Vindication for Bush 'freedom agenda'?

Loading...

| Washington

Does US foreign policy under President George W. Bush have anything to do with the pro-democracy protests now rocking the Egyptian regime and forcing accommodation elsewhere in the Arab world?

Events of the past weeks in the "greater Middle East" are, naturally, prompting scrutiny of US policy under President Obama and of the long US relationship with Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak. But they've also intensified a never-quite-ended boxing match about the "freedom agenda" of Mr. Bush, with some analysts arguing vindication for his attempt to speed democracy to the region and others suggesting the former president's policies did more harm than good to pro-democracy forces there.

In one corner are those who say Bush was right: It is about freedom and democracy. They argue that the US would be better off in the region today if the Obama administration had pursued Bush's vision of regime change in the name of the people’s rights and freedoms, instead of taking a pragmatic tilt to accommodate dictatorial regimes such as Iran in 2009 and other Arab countries more recently.

RELATED – Egypt protests: People to watch

In the other are those who cite the Iraq war, which Bush pursued at least partly to create a beacon of democracy in the region, as perhaps the single most significant setback for pro-democracy advocates in the region in the past decade.

The debate over the Bush “freedom agenda” may have found its best opposing arguments so far from two Washington thinkers.

Elliott Abrams, a deputy national security adviser in the Bush White House, says the former president believed fervently that Arabs have the same yearning for “liberty” as other people and that dictatorships “are never truly stable.” Recent events in Tunisia, Egypt, and Yemen “seem to come as a surprise” to the current administration, which cast aside the "freedom agenda" as "too ideological," says Mr. Abrams, now a senior fellow for Middle Eastern Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Writing Sunday in the Washington Post, Mr. Abrams quoted Bush as saying in a 2003 speech, “As long as the Middle East remains a place where freedom does not flourish, it will remain a place of stagnation, resentment and violence ready for export.” He himself added: "[T]he revolt in Tunisia, the gigantic wave of demonstrations in Egypt and the more recent marches in Yemen all make clear that Bush had it right – and that the Obama administration’s abandonment of this mind-set is nothing short of a tragedy.”

An opposing view comes from Shibley Telhami, a Middle East expert at the University of Maryland and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. He argues that above all the US must refrain from imposing an outcome in the region – no matter how democratic and freedom-oriented its own vision might be. “When the Bush administration used the Iraq war as a vehicle to spread democratic change in the Middle East," he writes, "anger with the United States … and deep suspicion of US intentions put the genuine democracy advocates in the region on the defensive.”

The Iraq war, “waged partly in the name of democracy,” is what raised the passionate opposition of Arab publics and tarnished the name of democratization, Mr. Telhami, a specialist in Arab public opinion, wrote in an op-ed in Monday’s Politico. He agrees with Abrams that the wave of transformative events across the region might have occurred sooner – but he argues that didn't happen “because of the diversion of the Iraq war.”

Telhami’s point is that outside efforts to impose democracy – especially by force – will only set back its forward march. He includes Iran in his analysis, writing, “one wonders whether the Iranian people might succeed [in toppling the clerical regime] if the regime were robbed of its ability to point fingers at the West.”

The showdown in Egypt is raising many pressing questions in Washington: When should the US throw in the towel on a longtime ally who is also a dictator? Does Egypt, after decades of suppression of political opposition, have the makings of a functioning interim government that could keep order until fair elections could be held? What impact would a change of government in Egypt have on Israel and the Arab-Israeli peace process?

But the debate over the appropriate US role in promoting democracy in various corners of the world is central to the priorities of American foreign policy – and evidently it is far from over.