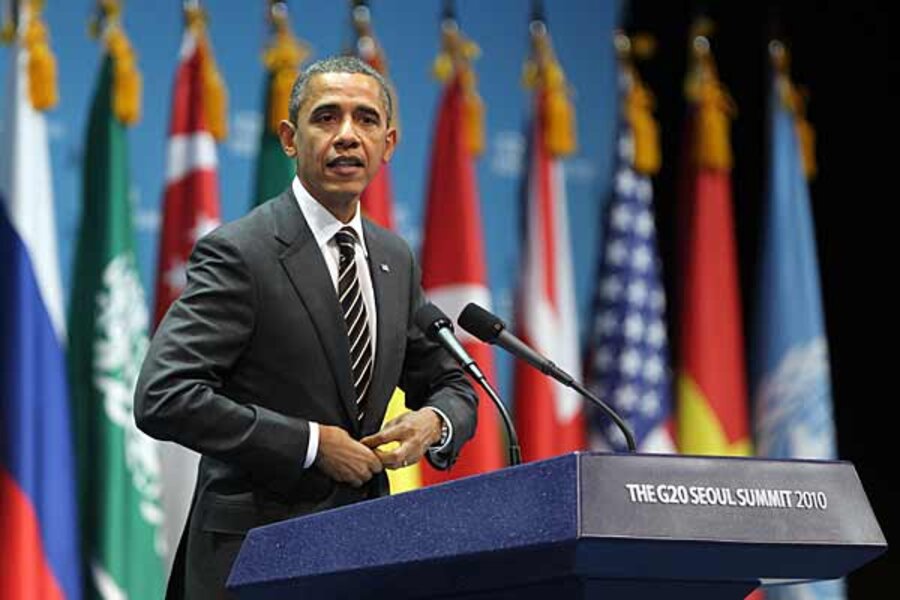

Why world leaders smacked down Obama at G20 summit

Loading...

| Washington

How do you say “shellacking” in Chinese? Or German? Or Korean?

Fresh from his self-described shellacking in this month’s midterm elections, President Obama has gotten pretty much the same treatment from foreign leaders as he has made his way through Asia this week.

Leaders at the Group of 20 (G20) summit in Seoul, South Korea – China and Germany topping the list – made it clear that they feel freer than ever to stand up to the United States on global economic issues. And South Korea refused to bow to Obama administration demands for reworking a US-Korea free-trade agreement dating from the Bush administration, putting off conclusion of the trade pact until at least next year.

Mr. Obama’s drubbing at the polls Nov. 2 is no doubt one factor in these countries’ willingness to stand up to a US president who remains popular in many of their countries.

“It would be naïve to say [the election results] don’t have an impact, because it does hurt him,” says I.M. Destler, who specializes in international security and economic policy at the University of Maryland’s School of Public Policy. “I’m just not certain that if the election had been much more positive for Obama, he would have done much better” in winning global support for his economic views.

Another, bigger explanation for the global defiance can be found in the state of the US economy relative to that of some of the US’s largest trading partners, global economic analysts say. China this year rocketed to the No. 2 slot of world economies (behind the US), while Germany’s unemployment rate is already several notches below the US’s 9.6 percent as German exports have boomed – despite slow overall German economic growth.

But perhaps nothing played a bigger role in lining up international opposition to Obama than the Federal Reserve’s action last week – pumping $600 billion in new money into the economy. The world saw that move as devaluing the dollar to make American products cheaper, rather than as an effort to stimulate US economic growth.

“Remember that before the G20, there was much more pressure on China than on the US in terms of this question of global imbalances” of deficits and surpluses, says Benn Steil, director of international economics at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) in New York. “But given the timing of the Fed’s actions,” just days before the summit, “it makes it look as if the US is behaving no differently,” he adds, “and China exploited that to the maximum.”

One result of the announced US plans? is that China and Germany suddenly found themselves on the same page in their opposition to global measures (as advocated by Obama) to address trade imbalances. “When the Chinese and the Germans find each other, you get a powerful coalescing of interests, and it emboldens them,” says Mr. Destler.

This rejection of the US vision of the way forward for the world economy is not new and certainly does not date from Nov. 2, some experts point out. But it is nevertheless easier for world leaders to tell Obama they do not agree with him when they believe the American people have just done the same.

Another explanation is that countries that early on in the global economic crisis rejected or mostly resisted Obama’s call for hefty stimulus spending to get the economy moving again believe that time has proven them right. German Chancellor Angela Merkel could rebuff Obama’s call for trade rebalancing measures in Seoul smug in the assurance that her nein to Obama’s stimulus prescription last year paid off – at least for Germany.

“Some of what we’re seeing, particularly in the case of Germany, is this feeling that ‘We were right,’ ” says University of Maryland’s Destler.

The G20’s final communiqué makes a bland reference to watching out for imbalances in trade accounts, but includes no triggers or mention of measures to be taken. And with countries watching out for their own bottom lines in a weak and uncertain global economy, coordinated economic action is not likely to flourish any time soon, international economists say.

“Prospects for common action are very tough at the moment and are unlikely to improve very soon,” says the CFR’s Mr. Steil. It will take a stabilizing of the value of the dollar – which remains the world’s major reserve currency – and a strengthening of the US economy for that to happen, he says.

It may also take a US president in a position of strength – which is not where Obama finds himself at the moment. “He looks very weak on the international stage,” says Steil. “You combine that with the US economy performing as weakly as it is, and it emboldens others to act in ways they might not have otherwise.”