U.S., India revive sweeping nuke deal

Loading...

| Washington

Considered a lost hope just last month, a US-India nuclear energy deal has sprung back to life and may yet end up one of the most significant geopolitical initiatives of the Bush presidency.

The pact is designed to provide India with American nuclear fuel and technology for civilian power while allowing it to retain its military nuclear arsenal. The accord is envisioned by the Bush administration as a way of cementing relations with the world's largest democracy while enhancing its role as a counterpoise to a rising China.

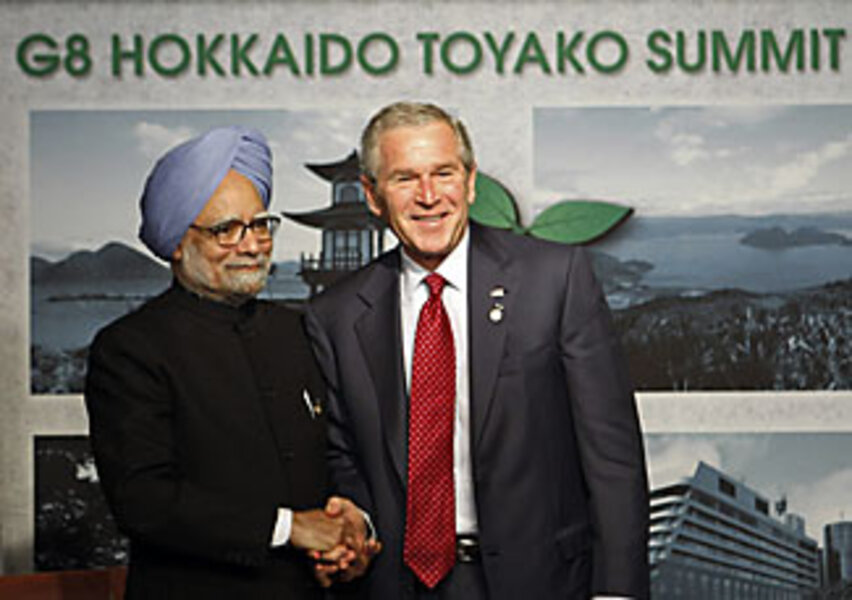

Both President Bush and Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh lauded the deal when they met Wednesday on the sidelines of the G-8 summit in Japan. Mr. Singh invoked nuclear cooperation as part of a new strategic relationship that has the US and India standing "shoulder to shoulder."

But the deal, reached between President Bush and Prime Minister Singh in 2005, still requires parliamentary assent in India and congressional approval in the US. While Mr. Singh appears to have raised the pact from the dead by eking out a small majority in favor, the accord could still get bogged down in the US.

Some members of Congress threaten to withhold approval unless India gives up its growing ties with Iran, while others have raised objections to a plan they say could end up providing India the uranium fuel it would need to produce more nuclear weapons.

And even if those concerns are met, there simply may no longer be enough time – given the approvals needed from key international players – for Congress to reach a vote on the deal.

"Does Congress have time to get this done before the year is out? We're hearing happy talk in Washington and New Delhi that everyone will have time, but I don't think so," says Darryl Kimball, executive director of Arms Control Association in Washington.

Before Bush can send a final deal to Congress, it must first pass through hoops at the International Atomic Energy Agency, and with the Nuclear Suppliers Group. The IAEA, the United Nations agency that oversees nuclear development, will be asked to approve a special safeguards agreement that covers a limited number of civilian reactors – while leaving India's military program outside those controls.

The US would then ask the Nuclear Suppliers Group – comprising 45 countries that oversee international trade in reactors and uranium supply – to exempt India from rules that require safeguards over a country's civilian and military nuclear programs before it can be supplied with fuel. Ironically, the NSG was created in response to the nuclear test India conducted in 1974.

Signs of the nuclear pact's new life are also resurrecting the opposition of many nonproliferation experts. They say a "sweetheart deal" that offers India access to modern nuclear technology and fuel without constraining its nuclear arsenal, will encourage other countries to hold out for a similar pact.

"This deal in effect draws a dangerous distinction between 'good' proliferators and 'bad' proliferators, and would weaken the nuclear safeguards system we've operated under for 40 years," says Mr. Kimball.

India has never joined the Non-Proliferation Treaty.

"It's bad enough you've just set an example with Tehran that if you wait it out long enough the US will cave and give you what you want," says Joseph Cirincione, president of Ploughshares Fund, a Washington-based foundation opposing the spread of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. "But you can bet Pakistan and Israel, among others, plan to take a cue from India and use this deal as a template for the future, not as some one-time agreement."

The US-India deal was judged to have little chance of passage last year when India's Communists, part of Singh's governing coalition, said they would oppose the accord which they considered would make India subservient to US interests. As recently as last month, some US officials were privately pronouncing the deal dead.

Singh formally lost Communist support from his coalition this week, but picked up the support of another small parliamentary group to make up for the loss.

India experts see the deal as a legacy issue for Singh, who faces rough parliamentary elections next year. "Legacy" is also a word that arises with respect to Bush, who came into office with a foreign policy team set on finding ways of countering China's rise.

"This deal offers a unique chance to set the direction of US-India relations on a productive path for the next administrations in Washington and New Delhi," says Bruce Riedel, a South Asia expert who served under three administrations and is now at the Brookings Institution in Washington. Failure to approve the deal this year would be a "serious setback," he says, but improvements in US-India relations in recent years mean "our partnership … is strong enough to survive if the deal falters."

Mr. Cirincione says members of Congress are right to question India's close ties to Iran, saying "it doesn't help that the country you want to give a sweetheart deal to is helping your adversary."

But Mr. Riedel notes that India has the world's second-largest Shiite Muslim population after Iran, "so it has to seek normal relations with Tehran." And counterbalancing that relationship, he adds, are India's "much stronger" ties to Israel.