New Hampshire primary: why the 2012 campaign is different

Loading...

| Manchester, N.H.

This is not shaping up to be a quintessential New Hampshire presidential primary.

Granite State voters take seriously their primary's first-in-the-nation status, knowing it can give the top candidates a surge of momentum in state contests to follow. By way of due diligence, they like to "kick the tires" of the candidates, hobnobbing with them at diners and tossing out unpredictable questions at town-hall meetings.

But this time New Hampshire may not be quite the proving ground it usually is. A host of nationally televised presidential debates and the use of social media appear to have usurped some of the traditional tire-kicking, leaving some voters here hungering for closer – and more substantive – contact with the candidates.

"There's much less opportunity to have small-group conversations with candidates" than in years past, says Elizabeth Hengen of Concord, N.H., an independent voter who is still weighing her choices. "The huge propensity for [large, multicandidate] debates has taken away the candidates' ability and time to circulate around."

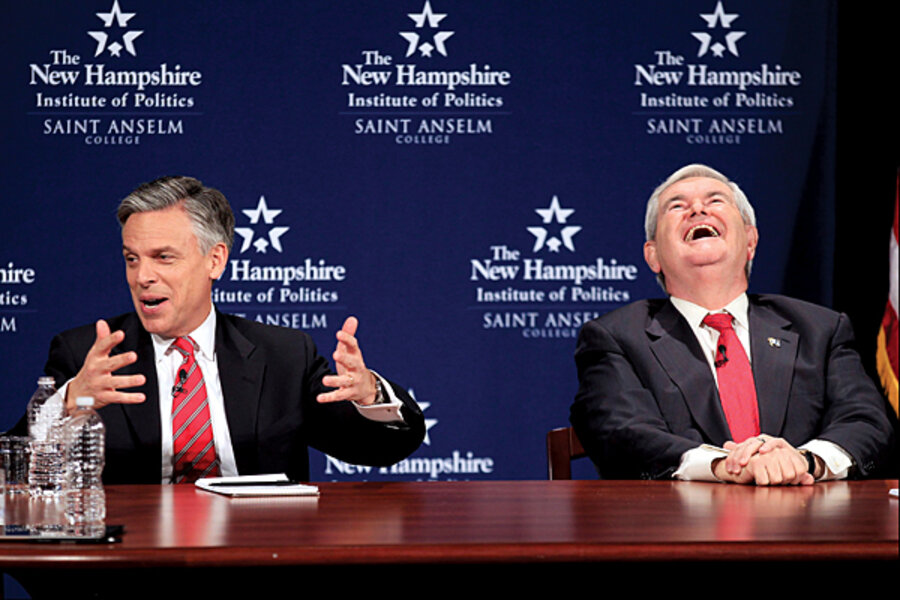

Ms. Hengen attended a recent forum at St. Anselm College here to listen to Newt Gingrich and Jon Huntsman Jr. detail their positions on foreign policy – and it was exactly the substantive discussion she'd been looking for. Sitting side by side, the two men expounded for a full 90 minutes on everything from conflicts in the Middle East to China as an evolving world power.

"This forum is very refreshing.... It gave the time to delve far below the usual sound bite," she said.

Still, when New Hampshirites go to the polls on Jan. 10, it is likely that many will have collected their information about the candidates in a more secondhand fashion than has been customary.

"The media primary has surpassed Iowa or New Hampshire this year – where voters are really getting their information from the Internet and from the [televised] debates in a way that they never have before," says Jennifer Donahue, a public policy fellow at the Eisenhower Institute at Gettysburg College in Washington.

That's not to say that the winner here (and perhaps even second- or third-place candidates) won't get a "bump" as they head into states that come next on the GOP primary calendar.

Moreover, what happens in New Hampshire – which has shifted since the early 1990s from "red state" to "swing state" – may give clues not only to GOP primary voters' proclivities, but also, and perhaps more important, to the GOP candidates' potential strength in the race against President Obama.

"If you can win the New Hampshire [GOP] primary, it's usually an indication that you will have a better chance in a general election because the New Hampshire Republicans are much more moderate – they're closer to the center of America's political distribution," says Andrew Smith, director of the University of New Hampshire Survey Center.

Why Romney resonates

Former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney has held a formidable lead in New Hampshire for months, and his appeal to voters here is multipronged, political scientists say.

Republican voters in the state tend to be fiscally conservative but not as passionate about socially conservative issues (think abortion and gay marriage) as Republicans elsewhere in the country – which is a better match for Mr. Romney's record. And Romney's Mormon faith isn't a barrier, as it may be elsewhere, because "Yankees ... think [your religion] is nobody's business," says Linda Fowler, a political scientist at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H.

Romney also has a home-turf advantage: He owns a lake house here, and voters are familiar with him from his 2008 bid for the nomination (he came in second, behind Sen. John McCain).

New Hampshire is "a must win for [Romney] ... and he's got to come in first by a decent margin" of about eight percentage points, Ms. Donahue says.

Nationally, Romney has struggled to expand his support, falling behind former House Speaker Gingrich in many polls.

The results of the New Hampshire primary "will give us a good indication of how deep the resistance to Mitt Romney is among Republican primary voters," says Scott Rasmussen, president of polling firm Rasmussen Reports.

Romney's support has been "soft" here, say many political experts. His lead over Gingrich shrank to between five and 18 percentage points in mid-December, depending on the poll – down from 38 points in June. The race overall is still fluid, they add, with slightly more than half of likely voters saying they still haven't made up their minds.

For months, Romney's team in New Hampshire ran "a very timid front-runner campaign ... and getting within 10 feet of Mitt Romney without going through [metal detectors], bomb-sniffing dogs, and at least one [body] cavity search is impossible," says Patrick Griffin, an unaligned Republican strategist and senior fellow at the New Hampshire Institute of Politics (NHIOP) at St. Anselm College, where he moderated the Dec. 12 Gingrich-Huntsman event.

But by mid-December, the candidate running second to Romney was Gingrich, not Mr. Huntsman, the former Utah governor who has been an avid in-person campaigner. Huntsman has set up his national headquarters here and has attended more than 120 events, joking that he's acquired a New Hampshire accent. But he is third or fourth in the polls – barely breaking double digits.

Gingrich was slow to hire campaign staff in New Hampshire, yet he now draws enthusiastic crowds of voters looking for a Romney alternative.

In contrast to Romney's well-groomed family image, Gingrich is a "Tasmanian devil in a dust storm ... who's unafraid to mingle with the great unwashed of the Granite State," Mr. Griffin says. "Perfection versus redemption – that's become the narrative of this choice between Romney and Gingrich," and redemption is easier for most Americans to relate to, he adds.

Registered Republican George Morin, in the audience for the Gingrich-Huntsman debate, said that although Gingrich "wasn't doing so well early on, I kept following him, and as the others dropped off I was happy to see ... Gingrich was keeping on point with his topics, not attacking the other Republican candidates." His support for Gingrich, he says, is "pretty firm."

The 'undeclareds' as wild card

Mr. Morin is part of a wave of former Massachusetts residents who have flowed north to New Hampshire in recent decades. Some have brought Democratic views along with them; many others, like Morin, wanted to escape the liberal leanings and relatively high taxes of the Bay State.

But migration from other states, for high-tech jobs that require high levels of education, has done just as much to nudge New Hampshire a little more toward the Democratic Party, contributing to its swing-state status, says Mr. Smith of the University of New Hampshire.

Between the early 1960s and early '90s, New Hampshire voters favored Republican presidential candidates. Then they swung to Bill Clinton in 1992 and '96, to George W. Bush in 2000, and back to Democrats John Kerry in 2004 and Barack Obama in 2008.

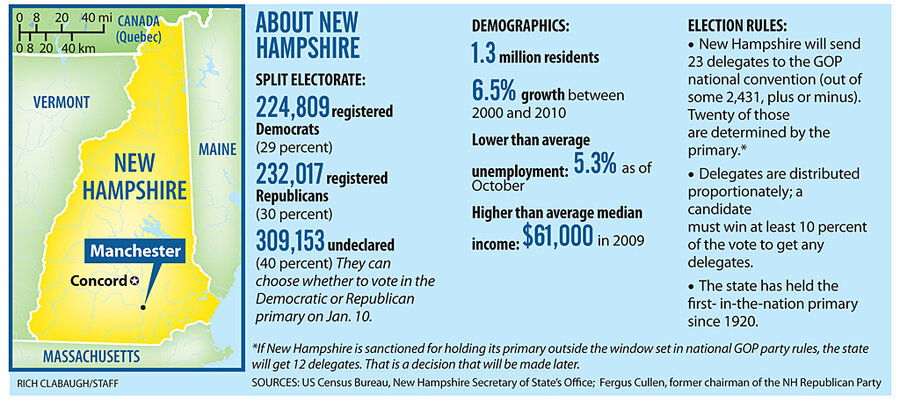

New Hampshire has a popular Democratic governor but in 2010 elected a strong majority of Republicans to the state House and Senate. Registered Republicans and Democrats are evenly split, and both are outnumbered by "undeclared" voters.

Because independent voters – 40 percent of the electorate – can decide on the day of the primary which party's contest they'll vote in, their role is always scrutinized. But it has proved to be difficult to predict.

In 2008, with contests in both parties, 55 percent of undeclared New Hampshire voters took part in the primaries, says Michael Dupre, a senior research fellow at NHIOP. In 2004, when only Democrats had a real race, just 38 percent did. He estimates that 40 to 45 percent will participate this time around.

Huntsman as spoiler?

Even though the plethora of national debates among GOP candidates has dominated the GOP campaign, including in New Hampshire, some political experts expect that the state will nonetheless reward candidates who have strong campaigns on the ground.

Huntsman, who has put all his eggs in the New Hampshire basket, could attract more Republicans if they grow weary of the fight between the Romney and Gingrich camps, or he could grab independents looking for a moderate voice, several experts say.

"He can't be underestimated at least for serious spoiler potential" because he would likely draw votes away from Romney, says political scientist Dante Scala of the University of New Hampshire.

But to beat expectations, Huntsman would have to outperform Rep. Ron Paul of Texas, who has a loyal base of support in this libertarian state, where the motto is "Live Free or Die."

Among independents in New Hampshire, Mr. Paul was leading in a Dec. 12 poll by Insider Advantage/Majority Opinion Research, with 24.1 percent support, trailed just slightly by Gingrich and Romney. Huntsman was fourth with 13.3 percent. Another poll that week showed Huntsman running second among independents.