Is your vote secure? Many digital systems lack paper backups, study says.

Loading...

In elections this March in Palm Beach County, Fla., an election management software glitch gave votes to the wrong candidate and the wrong contest. But paper ballots were available, and a recount was done. The mistake was corrected.

Such failures are hardly unique. And often they are worse. In every national election in the past decade, computer voting systems have failed with memory-card glitches and other errors that resulted in votes lost or miscounted, according to a new national study, "Counting Votes 2012: A State by State Look at Voting Technology Preparedness."

More than 300 voting-machine problems were reported in the 2010 midterm elections and more than 1,800 in the 2008 general election, according to the study by Common Cause, Rutgers School of Law, and the Verified Voting Foundation.

"Voting systems frequently fail," the study concludes. "And when they fail, votes are lost. Voters in jurisdictions without paper ballots or records for every vote cast, including military and overseas votes, do not have the same protections as states that use paper ballot systems. This is not acceptable."

Despite glitches and lost votes, America has survived. However, with the November elections just months away, danger lurks in the surprising number of states with computerized voting systems that lack any paper backup system – potentially opening the door to fraud or altered election outcomes, the study found.

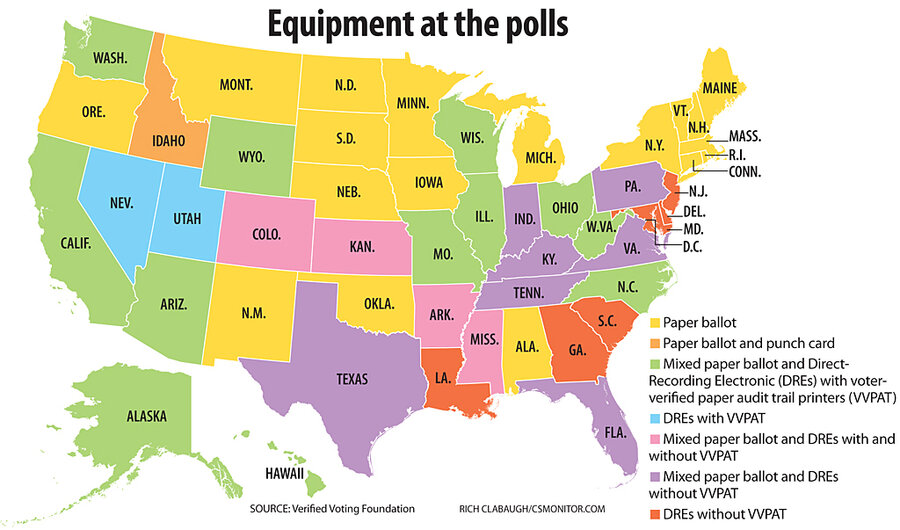

Computerized voting systems in 16 states – including some swing states – have no paper backup ballots or other paper trails "in some or all counties" and so could not reconstitute an accurate vote count from those machines if software or hardware fails, the report says.

Lack of audits – 25 states don’t do them – was another key problem, since paper ballots as a backup aren’t enough to ensure vote integrity.

"The problem is not just fraud and the threat that these systems can be manipulated, but that they are aging, complex systems where things go wrong," says Pamela Smith, president of the Verified Voting Foundation. "What matters most is: Can you recover from problems? Can you recover votes that are counted accurately? There are still way too many systems nationwide that can't do that."

States whose systems lack paper backups for some of or all their voting systems include: Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia.

"I'm amazed so many states do not have paper backups for their equipment," says Joanne Rajoppi, clerk of Union County, N.J., and the incoming president of the International Association of Clerks, Recorders, Election Officials, and Treasurers, a volunteer organization. "We have paper backup in New Jersey. If there's a challenge to show where your votes come from, you're going to have to prove it. It's only fair."

At the same time, 31 states have adopted new Internet-based systems intended to allow troops and other citizens abroad to transmit their vote home electronically. But while six of those states place some security restrictions on how completed ballots can be returned, 24 states permit electronic votes to be returned "without restrictions," thus running the risk of ballots being intercepted and altered, the study says.

Internet voting has been allowed in New Jersey ever since a US soldier requested a few years ago to send in his vote from his mountain outpost in Afghanistan, Ms. Rajoppi says. Yet New Jersey is the only state to require that the soldier also send in the original paper ballot as a backup.

A ballot sent via the Internet – including e-fax or e-mail – is "exposed to a far greater number of security threats including cyber-attacks such as modification in transit, denial of service, spoofing, automated vote buying, and viral attacks on voter PCs," the report says.

"We cannot overstate this fact: the technological reasons that 40 States have moved toward paper ballots or voter-verifiable paper records for voters at home also apply, with even greater urgency, to voted ballots returned to State and local election officials electronically from outside the country," the study says.

Officials from companies pioneering Internet voting disagree.

"We take security issues extremely seriously," says Lori Steele, chief executive officer of Everyone Counts, a San Diego-based Internet voting company that provides services in Colorado, Utah, Washington, Florida, and Illinois. "We use military-grade encryption and feel ours is the highest-level security of any voting system, including when you compare systems like mail or polling stations."

In Okaloosa County, Fla., Paul Lux, supervisor of elections, has had extensive experience with fledgling Internet voting systems, going all the way back to pilot tests in 2000. Today, the county is one of 13 in Florida that use LiveBallot, an Internet-based system developed by Democracy Live, a company in Issaquah, Wash., that specializes in voter information technologies.

In Florida's primary election in January, those counties had 140 overseas ballots returned using LiveBallot’s Web portal – Okaloosa having 99 such ballots, officials there report. Troops and others were able to mark ballots on their screens, then print them out. Although they still had to return their completed ballot by fax or mail, just downloading the blank ballot saved weeks.

"So far this program is going really well," Mr. Lux says. "Really, one of the biggest fears of those who don't like Internet voting is that once the door is open to overseas voters, everyone is going to want to do it. Why can't I vote at home?"

Downloading blank ballots and registration forms is no problem: In fact, it’s to be encouraged, authors of the study say. It's sending a completed ballot back by e-fax systems or e-mail that poses a serious threat.

"We believe the most secure way to return a ballot would be through our military-grade encryption," maintains Ms. Steele of Everyone Counts. "Certainly there's nothing secure about the idea of returning ballots by fax or e-mail. Using that as a stopgap isn't a very good idea."

Others say online voting systems aren't likely to be truly secure anytime soon because Internet security hasn't advanced enough.

"If an Internet target is attractive enough, we know it can be targeted from anywhere in the world," says Ms. Smith of Verified Voting. "If a company with the resources of a Google or the Pentagon can't prevent themselves from being hacked, how likely is it that a small, medium, or even large election district would have the ability to safeguard the process?"

Few know that better than J. Alex Halderman, an assistant professor of electrical engineering and computer science at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. In 2010, as a test of the supposedly robust Internet voting-system defenses in Washington, D.C., he led a team of students that successfully hacked into the system in less than 48 hours.

Picking through thousands of lines of code, he and his team located a single errant punctuation mark in one line of code that enabled them to get into the system and decide who got “elected.” They changed every vote and knew how everyone had voted.

Could newer and even more-robust Internet-based voting systems be hacked and votes be changed to favor one candidate, with nobody the wiser?

"If there's no paper backup, then we're completely reliant on the software in that machine to do the right thing," Professor Halderman says. "The problem is that you have to get almost all the details right at a superhuman level of perfection to avoid leaving the door open to tampering with the election result."

"We bank online, and people tend to think that voting should be no problem, either," he adds. "But it's going to be a long time before we solve this problem. It's just a lot more difficult than online commerce. It's going to be decades, if ever, before we are able to vote online – securely."