MIT via community college? Transfer students find a new path to a degree.

Loading...

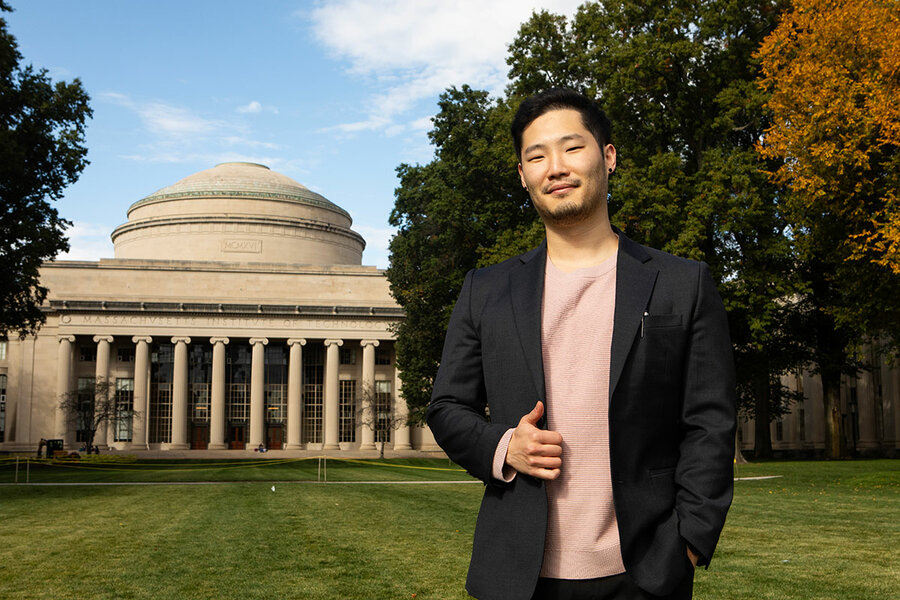

Subin Kim was headed to college at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona straight out of high school – until the United States Army came calling.

As a soldier, he did a tour in his native country of South Korea and back in the U.S. at Fort Drum in New York. After the Army, he settled in Virginia, where his wife is from, and enrolled in Northern Virginia Community College.

He always planned to pursue a college education, but he says what happened next was not what he expected: He ended up at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onTo help more people obtain a four-year degree, one initiative started with a simple idea: What if you make it easier for top community college students to connect with selective schools?

Mr. Kim is one of 32 community college students who have successfully transferred to some of the most selective U.S. colleges and universities through the Transfer Scholars Network. Launched in 2021, the TSN offers a path to top-tier schools such as MIT, Yale, and Princeton. These colleges and universities often have more resources to help support students complete a four-year degree – something fewer than 20% of community college transfers achieve within 6 years, according to new federal data.

“We did research back in 2018 that showed there were 50,000 community college students with at least a 3.5 GPA that would be competitive for admission at [selective] schools ... but were not going, were not considering, or applying to these schools,” says Adam Rabinowitz, a spokesperson for the Aspen Institute’s College Excellence Program, which helped create the network.

The idea was to bring those students – some 15,000 of which were at the top of their classes – to the attention of top-tier schools, he says, adding, “What can we do to create a network where they actually connect with community colleges?”

Close to 80% of community college students receiving federal financial aid plan to transfer to a four-year college and earn a bachelor’s degree, but only about 16% end up graduating within six years, according to new research released by the U.S. Department of Education in November. The rates for students from low-income families and students of color are even lower.

To make higher ed outcomes more equitable, “we need leaders to dramatically level up their support for transfer students,” said U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona in a press statement.

Overcoming doubts

Currently, 16 four-year colleges and universities, including Brown, Wellesley, Rice, and MIT, are a part of the Transfer Scholars Network. Many highly competitive schools have single-digit acceptance rates, with some hovering around 5%. MIT, for example, accepts only 4.8% of applicants. Community college advisers at participating schools look for first-year high-performing students, and invite them to apply to the Transfer Scholars Network. They consider students holistically – if they are veterans, parents, or first-generation college students. Students also must earn less than $100,000 annually.

Once they are accepted to one of the 16 partner schools, they receive financial aid packages that fill 100% of their need via grants, scholarships, and minimal loans. If students don’t get into one of those schools, they can still stay in the TSN and get mentoring help applying to other colleges and universities. Six hundred students overall have participated in the program, including 250 current students.

“One of the big challenges that we have ... is that a lot of times students just automatically assume that certain institutions, especially private institutions, are going to be too expensive,” says Jennifer Nelson, coordinator of university transfer and initiatives at Northern Virginia Community College, which, as a TSN partner, regularly sends students to elite schools. “Especially the institutions that are part of the TSN, they’ve made a commitment to making these educational experiences affordable for transfer students.”

Chase Kuhleman is a TSN participant and a senior at Cornell University majoring in applied economics and management. Classically trained as a pianist, he left high school in Pittsburgh wanting to major in music. While he applied to a few four-year colleges, the pandemic made getting access to studios a problem: He couldn’t send schools recordings of his playing. “I had to withdraw and consider a different route,” he says.

That route was online at Delaware County Community College, just outside Philadelphia. He got a 4.0 after his first semester and was recruited to join the TSN. The money tripped him up: He was raised by a single parent who makes just enough for him not to qualify for a Pell Grant.

“To be honest, I wasn’t really certain [about applying], because I know when you reach for really highly selective schools, they often come with a hefty price tag,” Mr. Kuhleman reflects. “So I thought it would be a really great thing, but also a pipe dream.”

He was accepted at Cornell, received a financial aid package, and was left with a bill that his single mom could afford to pay over his remaining two years.

The school paired him with other transfer students to help him acclimate to campus. He now has a GPA of 3.65 and plans to apply to Cornell’s law school next year.

At times he felt imposter syndrome at the Ivy League school, but he doesn’t like to dwell on the past. “I can definitely say sometimes I used to think, you know, do I really belong here?” he says. “But I also sit and think, I’m just glad to be here. I’m very fortunate to have found my way to Cornell.”

A small dent

Graduating with a four-year degree is often difficult for community college students.

“If there’s a higher percentage of students from disadvantaged groups in the community colleges, and you do something that’s just for the community colleges, you will be more likely to help students from those groups,” says Alexandra Logue, a scholar who wrote about the problems with transferring credits in her book “Pathways to Reform: Credits and Conflict at the City University of New York.”

Many community college students drop out after the first year, Dr. Logue says. They also can have trouble transferring credits to four-year schools, get discouraged because of the need to take remedial courses in math, miss registration deadlines, or simply never show up after admittance, she says.

Specialized programs, such as the Transfer Scholars Network, while helpful, she says, only make a small dent in the number of students who need help making the transition to a four-year school. At City University of New York, for example, there are about 10,000 students a year who transfer in, switching from an associate degree to a bachelor’s degree.

She also wishes bigger universities and highly selective institutions, beyond just committing to meeting financial aid needs, paid more attention to integrating new students into a campus community – like pairing them with other transfers and having support groups.

Transitioning was tough for Mr. Kim. Now a junior in his second year at MIT, he is 30 years old, but most other transfers who came in with him were 20 or 21. His wife stayed in Virginia to work.

His first year, he took courses like physics and Calculus 3 that required problem sets weekly after a series of lectures. Learning from other students made him sharper.

Having bright students learn from each other is by design, says Stuart Schmill, dean of admissions at MIT. “Every student that we admit, we’re looking for academic excellence and personal excellence,” Mr. Schmill says. “And the students that we’ve brought in from the Transfer Scholar Network and in general from community colleges are remarkable individuals.”

Many transfer students are humble, he adds, “but make no mistake, these are really outstanding young people.”

School is still not easy for Mr. Kim, but he has made friends as co-president of the Transfer Student Association and is working with the Student Veterans Association. His life philosophy has guided him from the start.

“What I experienced in the military helped me understand that if I want to get something,” he says, “I have to go out of my way to try, even if I fail.”