What does fair look like at America’s elite public schools?

Loading...

| Pasadena, Calif.

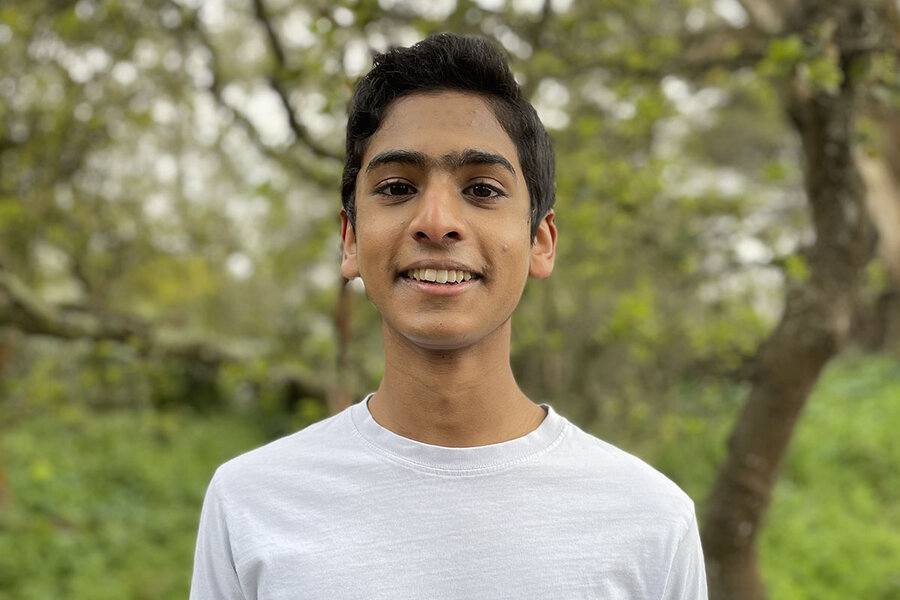

Vishal Krishnaiah, a rising senior at Lowell High School in San Francisco, finished the last of his seven Advanced Placement exams earlier in June. He loves his public school for its academic rigor, “amazing” teachers, and wide array of opportunities. He could have gone to a private high school, but he wanted Lowell. Fortunately, he had the grades – and the entrance exam score – to get in.

But that’s changed now. As with several other high-profile selective schools around the country, the local school board has dropped the entrance exam to Lowell, which graduated a Supreme Court justice and a Nobel Prize winner, among notables. A temporary measure begun under the pandemic – selection by lottery with no exam or grade requirement – has become permanent, fueled by the board’s concerns about racism and too few Black and Latino students.

Vishal says he understands the reasoning. “The school is overwhelmingly Asian and white and doesn’t exactly represent the population of our school district,” he says. But he worries about the effect of a lottery on the quality of the school and on students. It “breaks my heart” that some teachers are leaving or retiring, worried that without entrance requirements, Lowell will become like any other school.

Why We Wrote This

How should American public schools define merit? Black and Latino families argue a rigged system needs to change to allow more opportunity. But supporters of entrance exams, who are often immigrant families, say that change may deny them access.

“If we eliminate merit in schools, how does that set students up in the future?” he says. “If you grow up, and everything’s random, and you don’t have to work harder, what will students’ perception be of the real world?”

From colleges and universities dropping the SAT to proposals in California and elsewhere to delay math “tracking” of gifted students until the 11th grade, America is wrestling with the meaning of merit in education. It’s a discussion spanning decades, but one that has become particularly noisy and accusatory in the wake of the pandemic and a national reckoning on race. Are grades and tests the best measures of individual achievement? Or should public schools take a more holistic approach that accounts for context and increases opportunities for underserved students?

America’s deep roots in meritocracy

“The American bias is very firm. Our history is as an individualist nation,” says Anthony Carnevale, director of the Center on Education and the Workforce at Georgetown University in Washington. “Americans like the fact that education has become the prime determinant of economic success and cultural status. And the reason they like it, they say over and over again, is that it’s based on merit. You have to go to school, do the homework, pass the tests, make your way into a good college, and get a good job.”

The problem, he and others say, is that K-12 public education is not a fair system. According to Dr. Carnevale, a child from a low-income family with top test scores in grade school has a 30% chance of getting a good job by age 25. On the other hand, a child from a family in the top income quartile, who has low test scores in grade school, has a 70% chance of getting that good job. It’s even worse for low-income minority students, he says.

“In this test score thing, you’re caught between Horatio Alger, and the basic reality of American life, which is that race and class matter a lot,” he says.

Critics of the current system point out that Alger’s writings were fictional and when it was coined, the phrase “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps” literally meant an impossible task. Add in America’s history of racism – from laws making it illegal to teach enslaved people to read, segregated schools, and redlining, which kept Black and other minority families from owning homes in good school districts – and they say it’s past time for change. But supporters of the entrance exams, who are often immigrant families, counter that education has long been the ticket to the American dream and that removing the testing component from these schools is yanking a ladder to the middle class out from under their children.

One possible way forward for K-12 structural reform, says Dr. Carnevale, is to legally hold governments responsible for promises to graduate students “college or career ready,” a ubiquitous claim. He also praises President Joe Biden’s goal of universal pre-K and two years of free community college. In the meantime, he says, the nation is now witnessing “a direct populist rebellion” as school boards do away with entrance exams to selective schools in order to expand access for underrepresented groups.

That’s true in San Francisco, Boston, Washington, New York, and northern Virginia, where officials have been under pressure for years to change admissions criteria to their elite schools. The pandemic, when many students could not gather for entrance exams and some districts’ grades became pass-fail, provided the procedural prelude to change. Nationwide protests after the 2020 murder of George Floyd by former police officer Derek Chauvin brought political pressure to a boiling point.

Boston has dropped the entrance exam at its three public selective schools for this year, while using grades and ZIP codes to allocate seats. At Boston Latin School, America’s oldest public school, the percentage of acceptance letters going to Black students increased markedly, from 6% last year to 17% this year. Latino admissions were up by 3 percentage points, Asians dropped by the same amount, and white students declined from 50% to 38%.

In Virginia’s Fairfax County, school officials dropped the admissions exam for Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, the top-ranked public high school in the United States. They switched to a “holistic review” based on grades, a “student portrait,” a problem-solving essay, and “experience factors,” such as students from underrepresented middle schools.

In December, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the elimination of screening for all selective middle schools for at least a year. But the crown jewels of the New York City public school system, eight selective high schools such as Bronx Science and Stuyvesant, still require an entrance exam, per state law.

Black and Latino students speak out

A coalition of city high school students, Teens Take Charge, filed a civil rights complaint in November demanding that the city drop “racially discriminatory” admission screens at all public schools – including standardized test scores, grade-point averages, and attendance and punctuality records. The percentage of Black and Latino students admitted to these schools keeps declining – to 9% this year. Nearly 54% of the students admitted are Asian American, and 28% are white.

Gabrielle Cayo, a sophomore at Brooklyn Technical High School who is a debater and helps run the Black Student Union, recalls taking an entrance exam prep course with mostly Black and Hispanic students. The material wasn’t based on their middle school curriculum and was completely new to the majority of students. She was the only person from the program to get into Brooklyn Tech, she said at a May Zoom event with Black and Latino students in the exam high schools. “I didn’t see any faces that looked like me at the school my first day, and I saw that numbers were lower than ever, which made me extremely disheartened.”

Sarai Pridgen, a senior at Stuyvesant, came from a private middle school in Brooklyn Heights. But in doing community service in middle schools in underserved areas, she met families who had never heard of Stuyvesant or the test. Families asked in Spanish about the Specialized High Schools Admissions Test: “What is the SHSAT? What is Brooklyn Tech?” “I don’t think this is an equitable system that’s working, and I think that the admission results speak for themselves,” she said.

Students at the Zoom event pointed to pervasive racism at the schools, like use of the N-word, questions about their academic integrity, and the humiliation of being singled out for promotion photos. And then there was the case of the student who wore a KKK mask to class. The isolation and trauma were not worth it, said one student tearfully, while another said more diversity would decrease racism.

These accounts sound remarkably similar to those voiced about Lowell. As the Rev. Amos Brown, president of the San Francisco NAACP, puts it: “For Black people in this town, and in urban communities across this country, the competition has not been fair. It’s been crooked.” In a school of 2,700, he says incredulously, Lowell has just 45 Black students.

“We’re either going to act like we’re a nation under God with liberty, and justice for all, or not.” Equality of opportunity – that’s the issue, he says. “Let people prove themselves.”

A counter-rebellion

But counter lawsuits are flying. The Coalition for TJ, a group of more than 5,000 parents, students, and others connected to Thomas Jefferson High School, is suing the county school board alleging discrimination against Asian Americans – who made up 73% of the most recent freshman class. They advocate instead for race-blind, merit-based admissions. Elsewhere, the U.S. Supreme Court is considering taking up a case alleging that Harvard University’s affirmative action policies penalize Asian students while boosting Black and Latino students. The university says it considers applicants individually, based on many criteria. It has urged the high court not to abandon precedent that allows admissions screening based partly on race to achieve a diverse student body.

In San Francisco, a lawsuit is challenging the process behind the school board’s decision to drop Lowell’s exam and grade screens and instead admit students according to a ranked-choice lottery used citywide. But the word “process” belies the outrage felt by those opposed to the change.

“Merit is not being redefined. I think merit is being defamed,” says attorney Lee Cheng of the Friends of Lowell Foundation, which was formed to restore merit-based admissions at the oldest public high school west of the Mississippi. The lawsuit is being brought on behalf of the foundation and two other groups. As one of the founders of the American Asian Legal Foundation, Mr. Cheng helped to eliminate race-based quotas at Lowell in 2000.

Tests and grades are imperfect measures of merit, he admits. But he says they are the most objective measures that show individual talent and a willingness to work hard, while more holistic criteria, including personality, are more subjective. He has less of an issue with a lottery, but Lowell’s is a “stacked” lottery that takes into account siblings, disadvantaged areas, and a particular middle school.

And while the lottery looks neutral on its face, he says the clear intent of the board is to reduce the number of Asian children, who account for more than half the student population. “That’s racist and should be illegal.” If the National Basketball Association decided to reduce the number of Black players because there are too many, there would be a hue and cry, he posits.

San Francisco’s Asian American community is particularly upset about tweets from one Black board member, who referred to Asians as “house N****rs.” They are stunned that, in the resolution about Lowell admissions passed by the school board, Asians are not included as people of color and appear to be lumped in with a “culture of white supremacy.” A wide diversity exists among Asians, who come from many countries and cultures. Neither are they all rich. Between 35% and 40% of the Asian students at Lowell qualify for free or reduced-price school lunches. It’s a similar story in New York.

“How will poor Asian American kids access Lowell?” asks Mr. Cheng, who describes his own journey to Lowell. He was a “latchkey” kid, both of whose immigrant parents worked. English was not his first language. He studied hard, and his reward for finishing his homework was watching a half-hour of news with Walter Cronkite. His father took him to take the entrance exam, with no test preparation. Later, to get into Harvard, he bought a Barron’s SAT prep book for $10.95. He got one of the highest scores in the city.

“It’s just a lie that nonwhite kids and kids who don’t have a lot of money ... can’t succeed.”

One Lowell parent, who asked not to be named for fear of retaliation, worries that the quality of the school will diminish without application requirements. Students must audition to get into the city’s public school for the arts. Why should a school for academics be any different?

“They think you get the best education at Lowell, so everyone wants an equal shot. They see it as an equity issue. I do not,” says the parent. “Any student with a certain aptitude should be able to go to Lowell. It has nothing to do with race.”

Allocating a scarce resource

And that gets to a common observation: Demand for public magnet schools exceeds the slots. “It’s basic resource allocation,” says Gregory Vincent, a civil rights attorney and educator at the University of Kentucky College of Education in Lexington. “What is the most effective, equitable way to allocate a scarce and valuable resource?”

This would be an issue even if it were all one group, says Dr. Vincent. Adding the racial dimension “exacerbates” it. With a limited number of slots, changing admission criteria is going to mean that some groups will gain while others will lose. “But there are losers now. There are Blacks and browns not getting in.”

Dr. Vincent, who is Black, is himself a product of a selective high school: Bronx Science. He was identified as gifted and talented in the third grade and kept on track by strong parental involvement. As the former vice president for diversity at the University of Texas at Austin, he played a crucial role in defending the university’s diversity practices, which were upheld by the Supreme Court in 2013. The San Francisco Board of Education has tasked University of Kentucky’s Education and Civil Rights Initiative, which Dr. Vincent directs, to do an equity audit at Lowell and come up with an action plan to address “exclusion” and “toxic” racism.

When asked what merit looks like, Dr. Vincent cites the Olympics. There’s a minimal score needed to compete, but every country gets to send representatives. The United States can only send a limited number of runners, even though these runners might be better than many runners sent by other countries.

“Merit is defined by what you are trying to achieve,” he says. If the goal is to have “the best of the best of the best” in a school, that’s a narrow goal. If it is to have a greater representation of students, that’s a broader goal. He thinks it’s possible to achieve both excellence and diversity, and favors a holistic approach to admissions, rather than falling into “the trap that tests tell you everything.”

It’s not clear what dropping entrance exams at selective schools will mean for the schools, students, or the quality of education.

“It’s a very difficult question. It puts people at odds with each other. People with good intentions and a sense of fairness,” says Dr. Carnevale at Georgetown.

But one way or another, he says, the country needs to work through this. It will have to find a way “not to deny anybody the fruits of their labor, and at the same time, provide opportunity for those who are less advantaged.”