After mass shootings, students hope to change sense of siege to surge in activism

Loading...

| Savannah, Ga.

As he has watched the aftermath of school shootings this year – including a massacre Friday in Santa Fe, Texas – Carson Collins has felt the pressure to grieve and move on. But that impulse, he told his dad, has been countered by an even stronger urge to not let go.

In December, a 21-year-old former student walked into Aztec High School in New Mexico with a gun. Carson, a senior, was one of those locked in a classroom, ready along with his fellow students to charge the shooter in the hallway right outside. Instead, the man killed himself after killing two students.

Reacting to an effort at Aztec High to help students heal by cheering them up, Carson told his dad: “When you think about it, it’s like you get punched in the gut ... and then they tell you to smile. I’m not prepared to smile.”

Why We Wrote This

Summer used to mean weeks of fun and freedom for students. This year, led by survivors of school shootings, summer means introspection and tackling a societal issue that had previously been seen as hopeless: gun violence in schools.

That sense of siege is being felt across the country as the school year draws to a somber close. “Everyone’s just talking about, ‘I hope we can make it to the summer, [that] nothing happens before ... we can get out of this place,’ ” says Marcel McClinton, a junior at Stratford High School in Houston.

Interviewed after traveling to Santa Fe to show his support for the community, Marcel and his fellow student activists represent an impulse that goes back almost two decades to Columbine High. After all, those students also lobbied Congress for curbs on gun purchasing. They failed, as did similar efforts by parents after the Sandy Hook shooting in Connecticut in 2013.

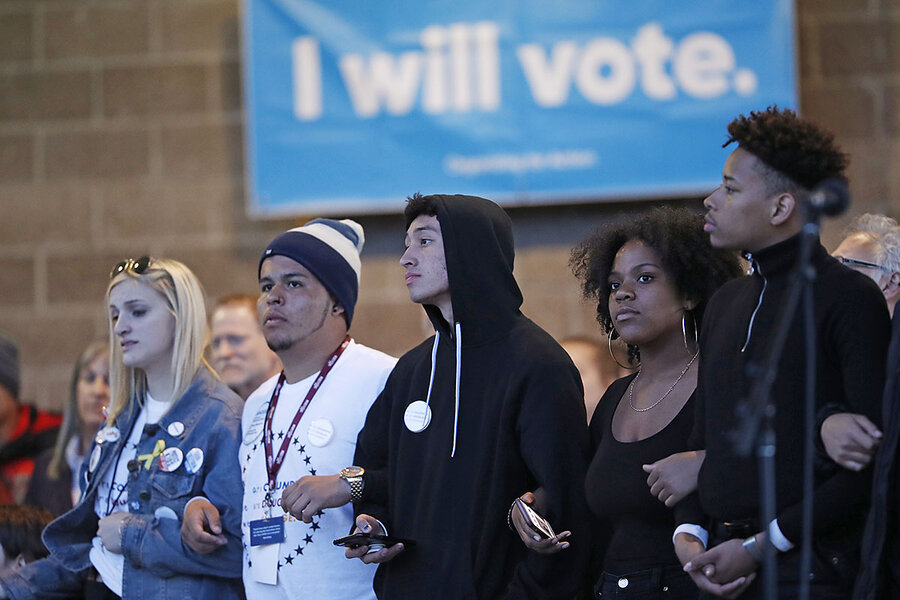

But this year, the March for Our Lives movement launched by survivors of the Parkland, Fla., shooting, has been boosted by a changing national mood and a generation that has put a new moral framework on the issue and is, by multiple measures, less violent than the ones before it. These students aren’t talking about jobs or the beach but rather about a summer of activism and soul-searching, seeking a sliver of hope that the United States will find a way to better protect its 50 million public school students. Last week, student activists announced dual campaigns: a summer tour to raise awareness and a voter registration drive to challenge politicians who oppose gun control measures. The appeals are already “moving the country like I have never seen,” former education secretary Arne Duncan told an education conference in San Diego last week.

“There is a very strong sense on this issue ... that we as a nation are at a breaking point, and the status quo feels to so many of us to be unsustainable,” says Angus Johnston, who studies the history of student activism at the City University of New York. “We feel complicit. And that, for a lot of us, is new.”

Nearly 20 years after the Columbine High School shooting in Colorado, two-thirds of US schools hold active shooter drills. Metal detectors have become ubiquitous. Increased guard patrols have likely reduced casualty tolls, and teachers in some districts are urged to come armed to class. Still, so far this year, the US has seen 13 school shootings where people were killed or injured, leaving a total of 32 dead and 65 injured – more than the casualty toll for America’s military.

“People are fed up with this idea of ‘now is not the time to talk about it,’ ” says Columbine survivor Paula Reed, who is still a teacher at Columbine. “Now is the time to talk about it. It just is.”

Historical trends upturned

Despite the headlines around mass shootings, younger Americans as a whole are bucking historical violence trends, to the point where teenagers are now more likely to have to bail their parents out of jail than the other way around, according to one juvenile crime expert.

“If you tell people that this generation of teenagers is less than half as likely to get shot to death as 25 years ago, people would think you are crazy, but it’s true,” says Mike Males, a researcher with the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice in San Francisco. “There is something about this generation that is more gun-averse than other generations, which is why I think they do speak with authority.”

And while the students march and help their peers to sign up to vote, state and federal governments also are searching for solutions – aware that the usual narrative is no longer seen as adequate. Gov. Greg Abbott began convening round tables Tuesday to discuss a way forward for his state, which is grappling with not only the Santa Fe shooting, but the massacre at a church in Sutherland Springs. “We want to hear from everybody,” he said.

Range of responses

In New Mexico, Aztec Municipal School District is one of a growing number of districts introducing the “Say Something” app created by parents of Sandy Hook victims. It allows students to anonymously report tips about disaffected classmates.

Last week, President Trump’s school safety commission met to discuss a federal response. Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have sought new resources for mental health and safety, most prominently by increasing funding for the federal Student Support and Academic Enrichment grants, by $700 million, to $1.1 billion.

About 200 universities and national education and mental health groups have signed onto the “Call for Action” program to prevent gun violence, rooted in proven methods for identifying and helping students who see violence as a solution to their angst.

In Florida’s Broward County, several of the Parkland victims’ parents are running for school board, determined to turn their frustration and grief into lasting change.

And student activists have vowed to keep up their rallies through the summer. A June 21 “die-in” event is planned in Washington for the second anniversary of the Pulse Night Club shooting.

“The most important thing ... is to keep remembering the victims and to keep them in our hearts,” says Nathan Dominguez, a March for Our Lives activist in Newton, Kan. “The second thing that we really need to remember is that the people on the other side of the aisle, we’re also doing this for them. We can’t make them out as our enemy. Those are our fellow Americans and they’re important in this process.”

Alexandria Aldred, a senior at Havelock High School, in North Carolina, was one of thousands who walked out of school earlier this year in protest. Her focus is on voter registration and gun control. But she says she is also keen to work with people who think differently about those issues.

“When I come across those [who disagree] I try to keep things level ... I try to keep it an adult-to-adult conversation where it’s calm and it’s not led by hate or emotion, it’s led by facts,” she says.

“There are a lot of people who believe that high-schoolers shouldn’t be involved in politics and that a lot of us don't know what we’re talking about,” Alexandria adds. “People need to start listening to us because at this point we know what we're talking about because ... we go to school with the fear in the back of our heads that we might not make it out of there today. And so I think that our opinions really matter and the older generations need to start listening.”

School board member: 'I need to step it up'

Roger Collins reacted to the Aztec shooting first by being a dad, making sure his two kids, including Carson, were safe. But his position as a school board member has also been affected, he says, in part by his town’s tragedy, but also by the response from his son and others of his generation.

“If kids are doing more than I am doing, I need to step it up for sure,” says Mr. Collins. “They brought that dialogue to the country and got people to the same table to discuss what schools are doing. They began the whole process of change. That makes you try to figure out what’s best for you and how can you try and make a difference in this community.”

For Sterling Haring, the activism has been enough to break his “physician’s silence” – an impulse by doctors to not get involved in politics.

Last month, Dr. Haring spoke at two March for Our Lives events, one in Nashville, the other in Benton, Ky., where two people died and 18 others were injured in a January shooting. Haring was one of the physicians at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville who treated the wounded from that school shooting. One of the teenagers rushed to his hospital died.

“There are those who have the luxury of becoming numb to this – and there are those of us who do not,” says Haring, a gun owner who says his hospital taken care of victims of three mass shootings in the past year: a Waffle House shooting, the Benton school killings, and the Antioch, Tenn., church shooting. “In the past, we've had these very taboo subjects – to remain friends with somebody you can't talk about things like guns – but I feel that’s kind of passing. No. 2, we’re starting to call a spade a spade. This has happened enough that the normal excuses aren’t working.”

The reaction in Santa Fe has been different from the one after Parkland. It is a far more rural and conservative town, for one thing.

Yet Marcel, the student from Houston, says that a broader sense that something is going amiss is being heard in Santa Fe, too. After attending a Sunday vigil and a youth group, he received a text from a group of girls who didn’t want to join March for Our Lives, but did want the group to help them get their message out.

The girls’ wish to shape their own protest was particularly telling to Marcel, who survived a mass shooting near Memorial Drive United Methodist Church in Houston in 2016.

“It is important to note that Houston, Dallas, and Austin are not Texas; Texas is Santa Fe,” he says. “Texas is rural, conservative communities where ... these kids are gifted shotguns when they’re 10, 11 years old. That’s their culture. I understand their culture. That is who they are. But as we approach these communities when things happen ... the story is not that the shooting happened. We know it happened. The story I think should be: Where do you move from this?”

Staff Rebecca Asoulin and Noble Ingram contributed to this report from Boston.