University of Missouri student president: School has racism but also unity

Loading...

| COLUMBIA, Mo.

When Payton Head ran as a gay, black man for student president at the University of Missouri — a school now known for one student's hunger strike and other protests against the administration's handling of racial bias and hostility on campus — he promised to "ignite Mizzou."

"We've definitely done that," Head, a 21-year-old senior from Chicago who is studying political science and international studies, told The Associated Press.

Recent racist incidents, including one directed at Head, and the perceived lack of response by administrators led to the hunger strike and a threatened boycott by the football team. Tensions seething at the school culminated early last week with the resignations of University of Missouri System President Tim Wolfe and Columbia campus Chancellor R. Bowen Loftin.

But despite the turmoil, Head is challenging a narrative that has come to define the university as a hotbed of hate and racism.

"The actions of a few members of our community don't speak for the majority," Head said. "The problem is when we have an administration, we have leadership who continues to send signals to these students that this kind of behavior will be tolerated on this campus."

That "allows these incidents to keep occurring," he said.

Head has spoken out publicly about his own experiences with racism during his time at the university, most recently in September.

He faced a turning point his sophomore year, when he said men in a pickup truck yelled racial slurs at him repeatedly as he was walking to a party. He said that was the first time he dealt with "blatant racism."

"It broke my heart, because I was really trying to find my place at Mizzou," Head said.

He said the event shook him so much that he considered transferring to a historically black college that had offered him a full ride. Instead, he stayed — motivated to push for change and social justice through student government.

He ran for Missouri Students Association president the next year. Head said he had been told he wouldn't win because he's black and at the time was not a member of a fraternity. To his surprise, he was elected in what turned out to be a record-setting election for voter turnout.

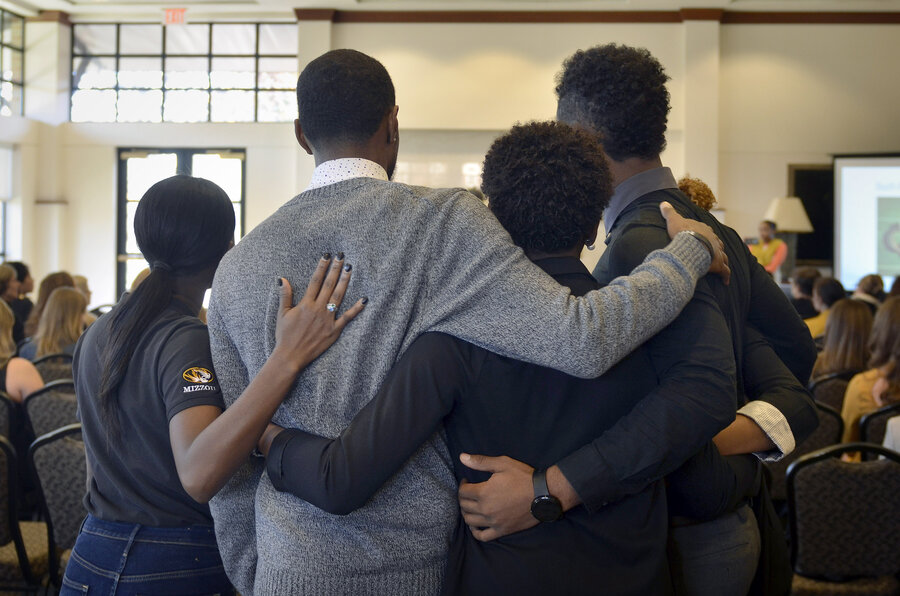

"Students want change, and students want an inclusive campus," Head told reporters Nov. 8 near the campsite of the Concerned Student 1950 group, where he joined members in calling for Wolfe to step down. Wolfe resigned the next day.

Head, who also has joined those students in protests and marches, has been both denounced and praised for how he has handled a difficult year.

He said he's received hate mail and death threats recently, mostly in response to his criticism of the administration.

He's also gotten blowback after posting on social media Nov. 10 about what police later said were unconfirmed reports of Ku Klux Klan members on campus in the wake of anonymous threats to students this past week, including a threat from one user to "shoot every black person I see." University of Missouri police Maj. Brian Weimer said that day that there was no evidence that KKK members were found in the area. Head has since apologized.

But Head added that he's also received "amazing" support from students, with some thanking him when they see him on campus.

Maiya Putman, director of student activities for the Missouri Students Association, said Head is generally "well-liked and well-received" by students, citing his involvement in social justice issues. She said the past few weeks have been hard on him and that he's handled the situation "the best way that he could."

"This has been a really tumultuous and challenging year," Putman said. "I don't know how anyone else would have been able to handle everything he's gone through."

Head, whose term ends in January, said it's been frustrating at times. He said he's tried to convey to administrators for a year that black students, disabled students and many others deal with discrimination regularly.

He said his first meeting with Wolfe didn't come until Nov. 6, days before students were to pick a successor for Head. The elections were rescheduled for this week because of the upheaval on campus.

With new administrators in place, Head has said tension likely will only heighten as some who might not have perceived racial issues on campus grapple with what has occurred.

At the same time, Head described the campus as "more united now than ever."

Racism "does exist; it's here," Head said. "But also there is love."