New York test scores hint at hard road ahead for Common Core

Loading...

The controversy surrounding New York State’s latest test scores hints at the difficult path most states can expect to tread as they begin to align tests to new Common Core State Standards in English and math.

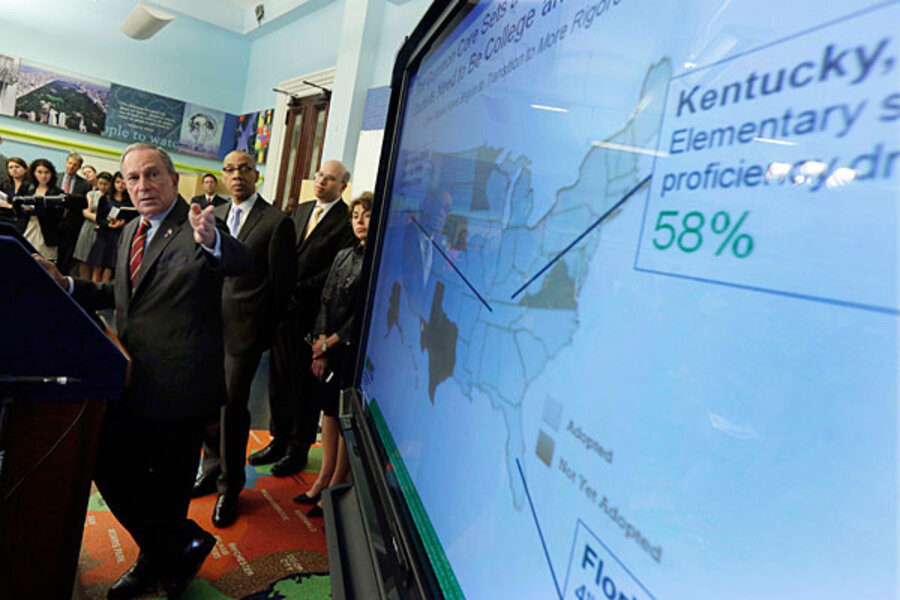

Just 31 percent of the state’s students in grades 3 to 8 were deemed proficient in math and in English language arts (ELA) on the new tests, compared with about 65 percent in math and 55 percent in ELA on last year’s tests. Kentucky, another leading-edge state implementing its own common core tests, experienced similar declines in scores last year. Most of the 45 states that have signed on to the Common Core are waiting until at least 2014-15 to implement common tests that are still in development.

For those who support the Common Core, a set of standards for college- and career-readiness in the 45 states that have voluntarily adopted them, the drop in New York’s scores offers a more honest benchmark. It shows how much work schools need to do to prepare students for future success in colleges and careers. It’s predictable in the early stages, they say, but over time, teachers and students will adjust to new demands and come out ahead.

The scores, released Wednesday, “reflect the hard truth that students are struggling to meet these higher goals,” said Chris Minnich, executive director of the Council of Chief State School Officers, one of the groups developing the Common Core, in a statement.

Some critics of the Common Core, however, see it as a misguided attempt to create national standards. Others see it as yet another example of overreliance on testing and a way to label the public schools as failing to create an excuse for more privatization of education.

“The leaders of [New York] state seem intent on discouraging students, teachers and principals. Why do they want public schools to look bad?” wrote Diane Ravitch, an education historian and prominent critic of test-based accountability reforms, in an opinion piece for Newsday.

Common Core standards, and the tests associated with them, are controversial, and the New York results have given both sides fresh material to support their side of the debate.

“It’s a complicated issue, transitioning from one set of tests and standards to another … and people are spinning these results” based on their political agenda surrounding education, says Patrick McGuinn, a political science professor at Drew University in Madison, N.J.

In the middle, a number of groups are preaching patience with the Common Core but are worried that states will move ahead with the reforms without giving educators the resources needed to succeed.

“The low scores will be used by some as an excuse to throw out the Common Core or denigrate public education; those are the wrong lessons,” said Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, a national union, in a statement. But teachers need “a system that provides the resources and supports – the curriculum, the professional development, the time, and the extra help kids need to achieve the deeper knowledge and understanding embedded in the Common Core.”

The Center on Education Policy at The George Washington University recently surveyed 40 states about the Common Core. It found that state leaders are forging ahead with remarkable agreement that “the Common Core will do a better job of preparing students,” says Executive Director Maria Ferguson. But “people are really nervous about resources.”

School districts need the technology and teacher training to support new computer-based tests, which will automatically offer harder questions to more advanced students and easier questions to struggling students. The idea is to help teachers understand which skills students have mastered, but for it to be effective, teachers will have to learn how to diagnose student learning and make adjustments during the school year. Thirty-four of the 40 states surveyed said it was challenging to find adequate resources for all of the necessary Common Core implementation activities.

Researchers say the public should brace for several years where scores will look worse before they look better, perhaps expecting to see strong positive results from the new standards 10 years down the road, Ms. Ferguson says.

Kentucky hasn’t had to wait that long to see some encouraging signs.

The state adopted Common Core standards in 2010 and released its first test results aligned to those standards in November 2012. It had prepared the public to expect the lower scores and didn’t experience a strong public outcry, says Nancy Rodriguez, spokeswoman for the Kentucky Department of Education.

Its next round of test results won’t be out until the end of September. But meanwhile, Ms. Rodriguez says, the percentage of Kentucky students deemed ready for college or a career has increased from 34 percent in 2010 to 47 percent in 2012. That’s based on measurements such as the ACT college admissions test, the Kentucky Occupational Skills Standards Assessment, and the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery.

“Our students face very real challenges. But it's better to have our students challenged now – when teachers and parents are there to help – than frustrated later when they start college or try to find a job and discover they are unprepared,” said New York Board of Regents Chancellor Merryl Tisch in a statement Wednesday.

More than 40 business leaders in New York released a letter Thursday supporting continued implementation of the Common Core.

This year’s scores will not be used for school or teacher accountability purposes, and the high school class of 2017 will be the first group expected to pass the new tests in order to graduate, New York officials said.

While politicians and union reps in New York City have seized on the scores, which show below-30 percent proficiency among city students, to criticize Mayor Bloomberg’s education reforms, other cities such as Buffalo and Rochester fared even worse, with about 1 out of 10 and 1 out of 20 students, respectively, scoring proficient.

States recently received permission from the US Department of Education to delay tying test results to teacher evaluations until 2016-17.

With researchers still largely divided on how to effectively link test scores and teacher evaluations, many advocacy groups had pushed for that leeway. To its credit, Ferguson says, the Obama administration responded even though it had appeared to draw a line in the sand on that issue.