Is top-ranked Massachusetts messing with education success?

Loading...

| Boston

Heidi Stevens recalls the day that got her thinking about uprooting her family from California to move to Massachusetts. Frolicking with her boys at a playground in 1998, she wished some teenagers a happy Independence Day.

She was met with blank stares. "You know, the Fourth of July," she offered. Then they smiled and nodded, and she prodded a bit: "Do you know who we got our independence from?" One guessed France, another Mexico, and the last one said the Indians. "They were not kidding," Ms. Stevens says.

She enrolled her older son in first grade that year but wasn't happy with the emphasis on "creative spelling" and art projects. So she traveled to Massachusetts and visited public schools in Northampton, a town that boasts five colleges and universities within a short radius.

"We knew Massachusetts was a fabulous state for public education," she says. And she and her husband, both graphic designers, figured they could work from about anywhere.

The enthusiasm and skill of the second-grade teacher at the school in the Leeds neighborhood of Northampton "blew me away," Stevens says. "Meeting her sealed the deal that we would buy a house in that district."

They haven't been disappointed living in a state that by many measures sets the gold standard for public education in the United States.

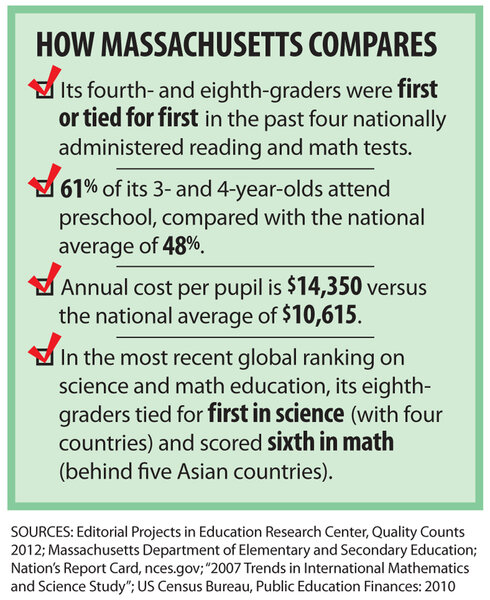

In national reading and math tests, the state's fourth- and eighth-graders have scored the best since 2005. Compared with the national average, greater shares of students here graduate from high school and score high on college-level Advanced Placement (AP) exams. The state even compares respectably with some of the top-performing countries.

Education's roots run deep in Massachusetts – home of the first public school in America and some of the best universities in the world. Its success, education leaders say, results primarily from a two-decade commitment to set high standards; hold students, teachers, and schools accountable; and offer funding and other key supports to help them reach expectations.

Other states have looked to the Bay State as a model in recent years as they've tweaked their own education strategies.

Massachusetts is "one of the major success stories in the country," says Gene Wilhoit, executive director of the Council of Chief State School Officers in Washington.

But now Massachusetts, like 45 other states and the District of Columbia, is revising its curriculum as part of a collaboration called the Common Core State Standards – a new chapter in education reform premised on the idea that to compete globally, the benchmarks for reading and math in all states need to reflect a richer set of skills to equip students for 21st-century demands.

Massachusetts could be a good test case for whether the Common Core approach lives up to that lofty rhetoric. President Obama has pushed for it through federal funding incentives, though critics say he has strong-armed states into de facto national standards, chipping away at state control.

For some education observers, Massachusetts has broken the axiom "If it ain't broke, don't fix it," and is in danger of watering down a key element of its success.

Others say just the opposite – that the new common standards are at least as strong as Massachusetts' previous ones and could catapult more states to heights that the Bay State has already achieved.

"One of the provisions ... was that no state would have to lower its standards in order to adopt the Common Core.... So the Massachusetts standards became a benchmark [in] developing the [new standards]," says Mr. Wilhoit, whose organization is coordinating the Common Core initiative.

Despite the state's attainments, there are always areas to improve, education leaders here say – particularly when it comes to achievement gaps for minority and low-income students

"One of our greatest potential hurdles will be complacency," says Mitchell Chester, Massachusetts commissioner of elementary and secondary education. "Once we are satisfied that we're doing it better than anyone else and that's good enough ... others will pass us by."

A key spark for education reform came in 1983 with "A Nation at Risk," a report warning that student achievement wasn't keeping pace – at home or abroad.

"In Massachusetts, people really took the report seriously," says David Driscoll, who became the state's deputy commissioner of education in 1993 and served as commissioner from 1999 to 2007.

Leaders from state government, education, and business came together to form the Massachusetts Education Reform Act of 1993, creating high standards and curriculum frameworks in math, reading, social studies, and science, as well as related tests for fourth-, eighth-, and 10th-graders – the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS).

To give those standards teeth, certain scores on 10th-grade tests became a requirement for high school graduation. Students scoring too low receive extra help and can retake the tests.

The emphasis on high-stakes testing led some teachers and parents to protest, worried that it would nudge borderline students into dropping out – a debate that later resonated nationally because of the testing regimen established by the federal No Child Left Behind Act of 2001.

"There was tremendous pushback, bills filed every year to do away with it, but we stuck with it," Mr. Driscoll says.

After the new system took hold, significant learning gains among Massachusetts students were reflected in both state and national tests.

The MCAS "made us feel as if Massachusetts had higher standards of learning than other states because that test is harder than other, average tests," Stevens says.

One big reason people came to accept the reforms: The state boosted education funding by more than 10 percent for each of the first six years – targeting the money largely to schools and districts with the highest needs. To date, the 1993 law has channeled $34.5 billion in extra state funding to school districts.

Strategies to boost achievement in Boston – the state's largest district – have included double blocks of time for reading and math instruction, as well as efforts "to get the best teachers teaching the kids that needed the most support," says Thomas Payzant, Boston's superintendent from 1995 to 2006.

In the 2010-11 school year, 97 percent of Massachusetts teachers were licensed specifically in the area they taught, and all teachers are required to earn a master's degree during their career, says Paul Toner, president of the Massachusetts Teachers Association.

Moreover, a statewide testing system for teacher applicants has helped bring up the quality of education.

Another factor: The state reform law set up a rigorous approval process for charter schools, many of which boast strong academic achievement.

Many parents in the state have high education levels and good incomes, making it easier to support their children's education. In addition, Mr. Toner says, school districts are relatively small, allowing for teachers to know the community better; any student can enroll in an AP course; and all students are encouraged to take college-entrance exams such as the SAT.

With high-stakes testing, some students do have to drill basic skills rather than enjoy a well-rounded curriculum as they approach 12th grade, Toner says, but "you'd have to admit that by having a graduation requirement ... it got kids' and families' attention and you could see the proficiency numbers on the exams [going] up."

Stevens says she has seen over time how the MCAS pressures teachers and presents a rather rigid structure for some learners. But her sons received a well-rounded education, including early opportunities to play musical instruments, which weren't available in California at the time. Older brother Nicholas O'Connor is now studying engineering at Boston University, and Benjamin O'Connor is a high school junior hoping to study marine biology.

"We understand the value of an education," Stevens says. "It's the one thing you can give your child that will last their whole life.

Because of Massachusetts' success story, education policies here are watched and sometimes "emulated by other states," Wilhoit says.

Texas, for example, adopted new math standards this year after a democratic process – starting with a draft based in part on standards from high-performing states, including Massachusetts, says Todd Webster, chief deputy commissioner of the Texas Education Agency. Texas is sticking with those standards rather than adopting the Common Core.

But Massachusetts' future doesn't look as rosy to observers such as Jamie Gass, director of the Center for School Reform at the Pioneer Institute for Public Policy Research, a conservative-leaning group in Boston.

"Massachusetts made historic gains ... but in the last four or five years, a lot of those policy gains have been rolled back," he says. "There are other states that are nipping at our heels ... [and] Massachusetts has kind of plateaued."

Particularly problematic, he says, is the state's decision to jump on the Common Core bandwagon. Massachusetts' standards were a model, he says, and the Common Core standards are of lower quality. For instance, standards for English-language arts used to be based largely on classic literature and poetry, which have a rich vocabulary, but the Common Core emphasizes more informational text, Mr. Gass says. To him it's part of a "trendy fad" focusing on workforce-development goals and "softer" 21st-century skills.

Commissioner Chester defends the state's decision to adopt the Common Core, saying it "advanced what we already had on the table."

Collaboration is increasing among states as more leaders look at the bigger picture of the global economy, Chester says: "When [there are] 50 different sets of standards [and testing] ... you're not necessarily giving children and parents honest and accurate information about how they measure up in a world where state boundaries are less and less relevant to your economic opportunities."