Girls and high school sports: complaints tag laggard schools

Loading...

Concerned about girls getting the short end of the stick in high school athletics? Now there’s a hot line to report inequities and seek advice about how to advocate for fair treatment.

The National Women’s Law Center (NWLC) launched the hot line – 1-855-HERGAME (437-4263) – and filed civil rights complaints against 12 school districts Wednesday as part of a broader campaign to highlight Title IX, a 1972 federal law that prohibits sex discrimination in public education.

There’s a “widespread pattern of schools failing to give girls as many chances as boys to play sports,” says Marcia Greenberger, co-president of NWLC, a Washington nonprofit advocacy group. The importance of participation extends beyond the athletic field, she says, because sports contribute to health, self-esteem, and school engagement.

Battles over college sports opportunities have received more attention in recent years, with a judge recently ruling, for instance, that Quinnipiac University in Connecticut could not count its cheerleading squad toward Title IX compliance because cheerleading lacks sufficient competitive opportunity.

But as progress has been made in college sports equity, “more attention is being directed to the high school level where for years not much has happened,” writes Shawn Ladda, president of National Association of Girls and Women in Sport, in Reston, Va., in an e-mail to the Monitor. Schools are also coming under more scrutiny now, she notes, because the Obama administration is more committed to enforcing Title IX than was the Bush administration.

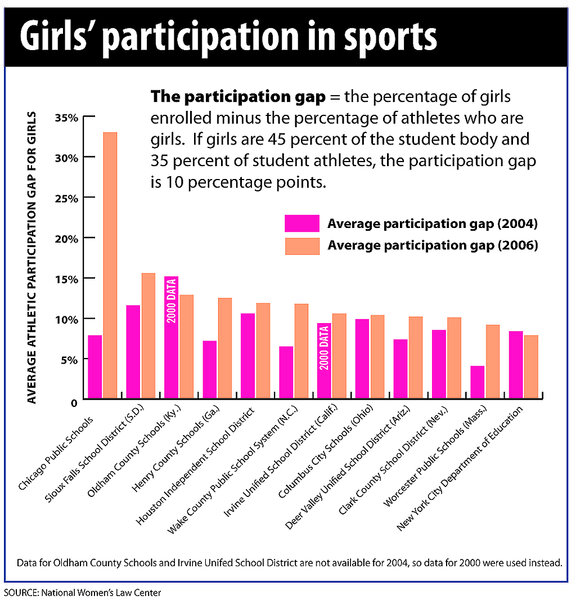

The 12 school districts – ranging from New York City to Houston – all show gaps in the level of female participation in athletics compared with girls' level of enrollment. The gaps in most cases grew worse between 2004 and 2006, the most recent year that schools had to report such data, according to the NWLC. (See chart).

In Chicago, for instance, the average gap was 33 percentage points – representing a “lost opportunity,” the center says, for more than 7,000 girls in 2006. At Marshall Metropolitan High School in Chicago, for instance, girls are 47.5 percent of the students but only 6.7 percent of the athletes. And some Chicago high schools report zero female athletes.

A spokeswoman for Chicago Public Schools says she could not comment Wednesday because officials are still reviewing the complaint.

Having girls and boys participate in sports proportionally to their enrollment in school is just one way districts can show compliance with Title IX. Another option is to persistently expand athletic opportunities for the underrepresented sex. Or schools can show that they are fully meeting the students’ interest in participating in sports.

Schools are not required to offer exactly the same sports for girls and boys, nor are they required to spend the same dollar amounts.

Many schools in the 12 districts cited do not give girls a chance to play sports that are widely played by high-schoolers in their state, the center notes. Examples range from soccer to gymnastics to bowling.

If districts have added significant opportunities for girls since 2006, it’s possible the Office of Civil Rights at the US Department of Education will find they are in compliance with the law. If they are not in compliance, the office will work with the district to settle on a plan to correct the imbalance. In most cases, such settlements are reached, but if not, a lawsuit could be brought to try to force compliance.

The National Women’s Law Center is urging schools to make sure they have a Title IX coordinator and is offering checklists for parents and concerned citizens who want to help monitor compliance in their school districts.

Critics of Title IX such as the College Sports Council often raise the concern that boys’ sports are likely to be cut if a school needs to show it is not offering more opportunity to boys than girls – especially during tight economic times.

That’s not how schools have to respond, and at the college level that’s usually not been the case, Ms. Greenberger says. “In these lean times, everyone has a responsibility to our sons and daughters to step up ... to [help] provide the resources that are needed.”

“The challenge of compliance is particularly difficult in big school districts where the buildings and facilities are old,” says Bruce Hunter, associate executive director of the American Association of School Administrators. They have to schedule early morning and late evening practice sessions to fit the growing number of teams into limited playing space, he says.

But Title IX is supported overall by school leaders because it expands student and parent involvement, Mr. Hunter says.

The National Federation of State High School Associations, a group of athletic and music directors, tries to educate schools and parent groups about Title IX. Parent booster clubs that raise money, for instance, shouldn’t be dedicated to just one sport, but to a school’s entire athletic program, says spokesman Bruce Howard.

“Schools today are more aware of what it takes and [that] they have to try to meet Title IX compliance,” Mr. Howard says.