Race to the Top: Do California, Florida have a chance?

Loading...

For states hoping to get a portion of the $4 billion that the federal government is offering to spur education reform, the announcement of the Round 1 winners Monday produced both guidance and questions.

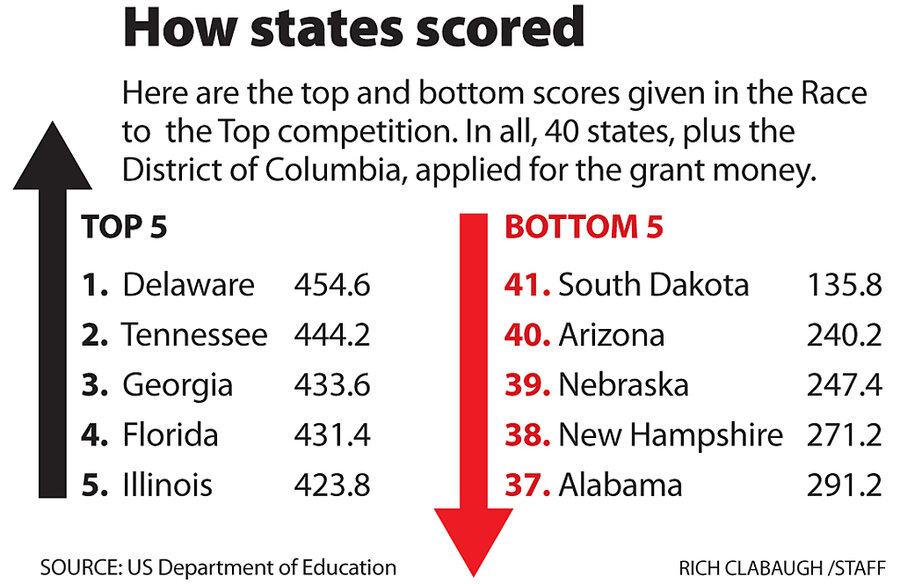

Just two states – Delaware and Tennessee – were awarded grants worth $600 million total in the first round of the Race to the Top competition. That leaves the bulk of the pot (about $3.4 billion) for Round 2, which has a June 1 deadline for applications.

The similarity of the two winners’ applications has led some observers to speculate about the elements that seem most important – such as sophisticated data systems, broad buy-in from state unions and districts, and a focus on linking teacher evaluations to student gains. Observers have also questioned whether it will be possible for other states, particularly ones that are larger and more complex, to win without those elements.

Meanwhile, the Department of Education has posted all 41 of the initial applications, together with their scores and reviewer comments, in hope of providing transparency and helping states realize what steps could improve their applications.

To some education experts, the decision to limit the first-round payout so much seems an attempt to gain as much leverage as possible from the competition, placing pressure even on those states with already-strong proposals to fine-tune their applications.

“It seems [Education Secretary Arne] Duncan wants to establish a very high bar and then have the rest of the states compete further,” says Jack Jennings, president of the Center on Education Policy in Washington. “The question has to be: Can the large states benefit from this program? Or just because of their size and complexity, will they be at a disadvantage?”

Others question the quality of the reviewers’ scoring, noting that they didn’t always reward states for particularly bold or innovative plans. And the scores and comments didn’t always take note of possible deficiencies. (Delaware, for instance, will allow a teacher to be labeled “effective” even if his student’s don’t achieve a year’s worth of growth.)

Delaware and Tennessee were among the few states to have both ambitious plans for reform combined with near universal support from districts and teachers unions, notes Andy Smarick, a fellow at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. “How many states are going to be able to replicate what Delaware and Tennessee pulled off?” he asks.

But in a conference call with reporters, Secretary Duncan cautioned against reading too much into the characteristics of the winners. “This is a 500-point competition,” he said. “There are no make-or-break categories.”

Still, many have been surprised not just by who won, but also by who lost. Louisiana – which, along with Florida, had been lauded for its visionary plans and was considered a favorite to win by many observers – ranked 11th. The state encourages charter schools and has a strong data system, significant experience in turning around low-performing schools, and an innovative plan to improve teacher effectiveness.

“Some of the states that didn’t win have a legitimate complaint that something was wrong with the scoring, based on the criteria and the things the department has said publicly about what they were looking for,” says Andrew Rotherham, a partner and co-founder at Bellwether Education, a nonprofit working to improve the achievement of low-income students.

Categories on teacher effectiveness and state ability to achieve goals, he notes, seemed very fuzzy in the end. Like others, he was surprised that Florida and Louisiana weren’t rewarded for their bold plans to develop more effective teachers, and he also thought that Indiana (ranked 23rd, and not a finalist) had some visionary ideas.

Mr. Jennings, meanwhile, was surprised at California’s 27th-place finish. The state had made a massive effort to change its laws, which meant controversial reforms to allow students in low-performing schools to apply to schools in other districts and to allow parents to force reforms at such schools.

In their notes, reviewers said they were concerned that California had received support from just 56 percent of districts, and among those districts, just 26 percent of local union leaders supported the initiative. “The lack of union buy-in at this stage raises serious concerns about the ability of the state to implement the Race to the Top reforms,” reviewers wrote.

But efforts in such large states are always more complicated, Jennings notes. “I would hate to think that states that have big problems with great complexity and huge numbers of students will just be written off because they can’t show as much coordination as smaller states,” he says.

However, smaller states may also have reason to complain: For Round 2, the administration is capping the amount of money states can seek. Under the new rules, small states like Delaware, which will receive about $100 million, can ask for no more than $20 million to $75 million. Large states (California, Texas, New York, and Florida) are capped at $700 million. Many states may have to adjust their requests.

In Round 2, Duncan has said he expects between 10 and 15 states to win. Winners will be announced in the fall.