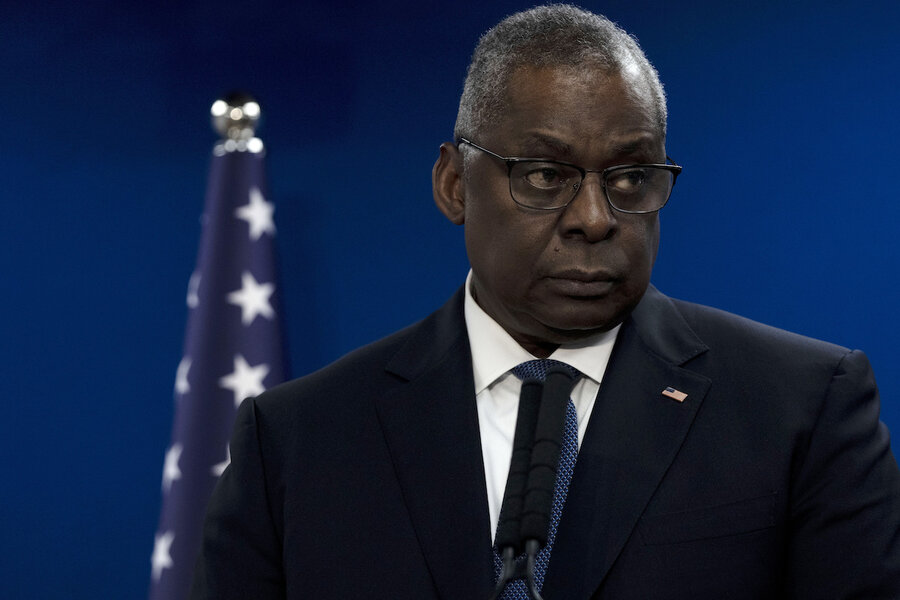

Secretary Austin was hospitalized for days before Biden knew. Why?

Loading...

| Washington

Both the White House and Pentagon said Jan. 8 they would look into why President Joe Biden and other top officials weren’t informed for days that Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin had been hospitalized. A Pentagon spokesman pointed to one reason: A key staffer was out sick with the flu.

Even as the Biden administration pledged to look into what rules or procedures weren’t followed, it maintained its silence about why Mr. Austin has been hospitalized for a week. Late on Jan. 8, the Pentagon issued an update saying Austin “is recovering well.”

Some Republicans have demanded Mr. Austin’s resignation, but the Pentagon said he has no plans to step down.

Mr. Austin went to the hospital on Dec. 22 for what the Pentagon press secretary called an “elective procedure” but one serious enough that Mr. Austin temporarily transferred some of his authorities to his deputy, without telling her or other U.S. leaders why. He went home the following day.

He also transferred some of his authorities to Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks after experiencing severe pain and being taken back to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center by ambulance and put into intensive care on Jan. 1. The White House was not informed he was in the hospital until Jan. 4.

Mr. Austin, who resumed his duties on Jan. 5, is no longer in intensive care. Maj. Gen. Pat Ryder, the Pentagon press secretary, said his prognosis is “good,” but it is not known when he will be released.

The Pentagon said Mr. Austin has continued to receive briefings and make calls to senior leaders. On Jan. 8, he spoke to national security adviser Jake Sullivan and got briefings from Ms. Hicks; Gen. Erik Kurilla, his top general in the Middle East; and the Joint Chiefs chairman, Gen. CQ Brown Jr.

The failure to properly inform government and defense leaders will be the subject of what John Kirby, the National Security Council spokesman, called a “hotwash” to see if procedures need to be changed.

Mr. Kirby, speaking to reporters on Air Force One as Mr. Biden traveled to South Carolina, said there is an “expectation” among members of Biden’s Cabinet that if one of them is hospitalized, “that will be notified up the chain of command.”

On the evening of Jan. 8, the Pentagon announced in a memo it would review how authorities are transferred and specifically focus on the events and decisions surrounding Mr. Austin’s hospitalization, to ensure that in the future, “proper and timely notification has been made to the President and White House and, as appropriate, the United States Congress and the American public.”

The late Jan. 8 memo also vastly expands the circle of people who will be notified in future transfers of authority. During the week of Mr. Austin’s hospitalization, Ms. Hicks and her staff received the transfer of authority notification through email, but it was limited to them and without explanation.

Going forward, any time authority is transferred a wider swath of officials will also be notified, to include the Pentagon’s general counsel, the chairman and vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Combatant Commanders, service secretaries, the service chiefs of staff, the White House Situation Room, and the senior staff of the Secretary and Deputy Secretary of Defense.

On Jan. 8, Mr. Ryder acknowledged that he and other public affairs and defense aides were told Jan. 2 that Mr. Austin had been hospitalized, but did not make it public, and did not tell the military service leaders or the National Security Council until Jan. 4.

“I want to offer my apologies and my pledge to learn from this experience, and I will do everything I can to meet the standard that you expect from us,” he said.

Mr. Ryder said staff in Mr. Austin’s front office will review notification procedures, including whether regulations, rules, or laws were broken, and will take steps to improve the notification process. Those staff members, however, are among those who did not disclose the secretary’s hospitalization.

Mr. Austin has taken responsibility for the delays in notification.

“I recognize I could have done a better job ensuring the public was appropriately informed. I commit to doing better,” he said, acknowledging the concerns about transparency, in a statement he issued Jan. 6. “But this is important to say: this was my medical procedure, and I take full responsibility for my decisions about disclosure.”

Mr. Ryder provided some more detail on who knew about the hospitalization and when they were told.

He said when Mr. Austin was taken back to the hospital on Jan. 1 he “was conscious but in quite a bit of pain.” He spent that evening undergoing tests and evaluation. The next day, “due to the secretary’s condition and on the basis of medical advice,” some authorities were transferred to Ms. Hicks through a standard email notification that often does not provide the reason for transfer, Mr. Ryder said.

Ms. Hicks, who was in Puerto Rico, was not told the reason for the transfer of authorities until Jan. 4.

Mr. Ryder said Mr. Austin’s chief of staff, senior military adviser, and the Joint Chiefs chairman were notified of the defense secretary’s hospitalization on Jan. 2.

Mr. Ryder said the chief of staff, Kelly Magsamen, did not inform the White House because she had the flu. He said Ms. Magsamen told Ms. Hicks on Jan. 4 and they began drafting a public statement and developing plans to notify government and congressional officials that day.

But the congressional notifications did not begin until the evening of Jan. 5, just minutes before the Pentagon issued its first public statement on Mr. Austin’s status.

Asked who approved the U.S. military strike in Baghdad that killed a militia leader on Jan. 4, Mr. Ryder said it was pre-approved by Mr. Austin and the White House before Mr. Austin was hospitalized.

Sen. Jack Reed, a Democrat from Rhode Island who chairs the Senate Armed Services Committee, and the only member of Congress Austin contacted about his hospitalization, called it a “serious incident” and said there needs to be accountability from the Pentagon.

New York Rep. Elise Stefanik, Sen. J.D. Vance of Ohio, and Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas, all Republicans, have called for Mr. Austin to resign. Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell did not answer when asked if Mr. Austin should resign.

“This lack of disclosure must never happen again,” Mr. Reed said in a statement. “I am tracking the situation closely and the Department of Defense is well aware of my interest in any and all relevant information.”

Democratic Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois said letters requesting additional information from Mr. Austin are being sent.

“There’s a lot of pressure,” Durbin said. “It’s not over by a longshot.”

Still, White House officials on Jan. 8 emphasized that Mr. Austin retains Mr. Biden’s confidence. White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said Biden appreciated Mr. Austin’s statement on Jan. 6, in which he took responsibility for the lack of transparency.

“There is no plan for anything other than for Mr. Austin to stay in the job and continue the leadership that he’s been demonstrating,” Mr. Kirby said.

This story was reported by the Associated Press. AP writers Tara Copp, Mary Clare Jalonick and Lisa Mascaro contributed to this report.