What is an apology without justice?

Loading...

| Akwesasne Mohawk Territory

When Doug George-Kanentiio was taken from his people’s native land in the 1960s at age 11, he was sent to a residential school in Brantford, Ontario.

Marjorie Kaniehtonkie Skidders’ mother was taken from the same territory in the 1930s when she was just 8, but she was sent to an institution south of the border instead: the Thomas Indian School in New York.

Today, Mr. George-Kanetiio and Ms. Skidders work on the committee for Akwesasne Mohawk residential school survivors, as chairperson and a board member respectively, to identify which Akwesasne Mohawk children never returned home because they died in such schools.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onDo apologies matter? Some Native people say no – and that governments should ask how to make reparations, rather than assigning their own.

Their work spans the modern U.S.-Canada border just like the Indigenous territory itself, situated along the St. Lawrence River in parts of New York, Ontario, and Quebec. But they face two historical perpetrators that are in very different stages of acknowledgment and apology.

While Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized for the residential school system in 2008, the United States has never done so publicly. It has only recently begun a thorough examination of the harms wrought by forced assimilation of Native Americans in the 19th and 20th centuries.

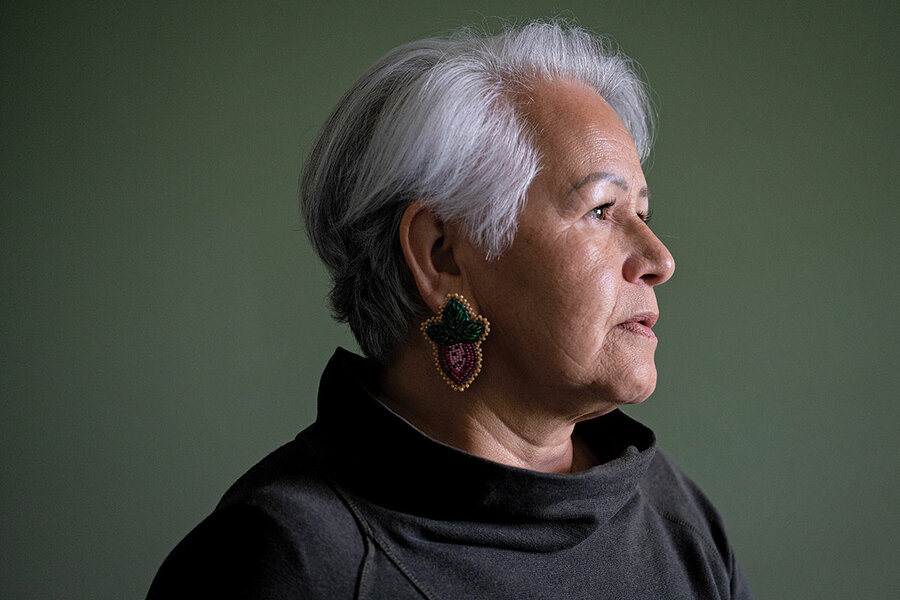

“Some people don’t put any weight on an apology, but I do,” says Ms. Skidders.

Like many here, she doesn’t distinguish between Canada and the U.S. She says her identity is Kanien’kehaka (Mohawk), and she doesn’t think either government has come close to any kind of true reparation for Indigenous peoples. For many, reparations dictated by governments, without justice for those wronged and their heirs, are of limited value. “But you need to acknowledge what has happened here, the trauma that has so severely affected a whole generation of people, and also the next generation that came after them.”

The U.S. government has officially apologized to Native people in the country, but almost no one is aware of it.

That’s because instead of being read at the time it was issued in 2010, the statement sits as an amendment to a Department of Defense budget bill, between an appropriation to counter drug trafficking and a section about agency reporting requirements.

The apology came out of a prayer meeting in 1996 between then-Sen. Sam Brownback and Negiel Bigpond. The Kansas Republican, descended from homesteaders who settled on lands promised to tribes in federal treaties, met the member of the Yuchi Tribe of Oklahoma, who is a boarding school survivor. After praying over the Bible and a book of the 370-plus treaties – many broken – between tribes and the U.S., they agreed that an official apology was needed.

“We’ve got obvious racial divisions,” Mr. Brownback says. “You’re [not] going to see healing and racial reconciliation without an acknowledgment of past wrongs, and an asking of forgiveness.”

But his efforts to pass an official apology through Congress failed for years. So in 2010, in a classic Washington move, it was tucked inside a larger bill that Congress would eventually pass. But the apology has never been publicly read by a U.S. president.

The country’s hesitation to apologize stems from questions of liability, guilt, and simple unknowing. Robert Miller, a professor at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law and a citizen of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe, says that many Americans genuinely ask themselves why they are responsible for what happened 200 years ago, from the stealing of Native lands to forced schooling. “We don’t really want to know what happened in the past,” he says.

Yet an apology now to Native Americans, says Mr. Bigpond, would “heal this land, and the people, and change the nation.”

Mohawk territory once spanned over 9 million acres across New York up to Montreal. Today Akwesasne, which means “Land Where the Partridge Drums,” counts only some 27,000 acres on both sides of the border.

Amid the loss of territory and the suppression of culture, the limits of apology are clear to many Akwesasne Mohawks.

For Mr. George-Kanentiio, Mr. Harper’s words were practically meaningless. Mr. George-Kanentiio stands along the St. Lawrence River, where he spent summers as a boy swimming and fishing before he was taken away. His mother died when he was 10 and his father couldn’t care for 12 children, so Mr. George-Kanentiio was sent to the Mohawk Institute Residential School, originally operated by the Anglican Church.

“It wasn’t a school in the Canadian sense in that you were praised,” he says.

Instead he, like all the children, was assigned a number: 4-8-2-738. He experienced mental and physical abuse from the start – a common experience across more than 130 residential schools that operated in Canada, where children were forbidden from speaking their native languages or practicing their spiritual beliefs.

“The first act is kidnapping. And then it’s alienation, separation. And then that builds up in the child,” Mr. George-Kanentiio says. “You feel resentment and anger towards your family and towards the community, because they failed to come to your aid when you were there.”

Canada’s residential school system was established in the 19th century as a network of government-sponsored religious schools, the majority of them Roman Catholic, aimed at assimilating Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian society. But according to the 2015 findings of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, it amounted to “cultural genocide.” An estimated 150,000 children from three Indigenous groups in Canada – First Nations, Inuit, and Métis – were removed from their homes. The last school did not close down until 1996.

“An apology without an absolutely unqualified commitment to justice to me doesn’t mean anything,” Mr. George-Kanentiio says. Instead, he is channeling his work into the Akwesasne residential school survivors committee, formed a year ago, to find any graves where students were buried. “Getting the kids home, that’s our overwhelming priority.”

An apology is also seen as just another colonial imposition, where the federal governments set the terms, says Waylon Cook, an Akwesasne Mohawk who works for the Akwesasne Freedom School. “The damage is done. Whatever they do, it’s too late.” Instead, he sees the solution in initiatives like the Freedom School, an elementary school that teaches Mohawk language and culture.

For Mr. Brownback, however, all forward movement must start with the apology. “[Apologies] really only begin the process,” he says. “You can’t get to [reconciliation] without doing this.”

Upon becoming governor of Kansas in 2011, he apologized “on behalf of the people of Kansas to all Native peoples” for the violence, maltreatment, deception, and neglect inflicted on them. Nearly 30 tribes were forcibly relocated to the area in the 1830s, according to the Kansas Historical Society, and after another round of forced relocation decades later, there are now only four tribes remaining in the state.

Those relocations, like Native boarding schools and other historical injustices, were engineered by the U.S. government, not states. The U.S. government is only just beginning a reconciliation process. In 2021 the Department of the Interior announced an initiative to investigate the legacy of federal American Indian boarding schools. The Native American Boarding School Coalition, an advocacy group, had been conducting its own investigations of U.S. boarding schools since 2012. Drawing on official records and firsthand accounts from survivors, the coalition reported that 83% of Native children were in boarding schools in 1926, with the schools “directly responsible” for physical and sexual abuse as well as loss of tribal culture.

While the DOI initiative is seen as “an important first step,” the coalition wants a congressional probe into U.S. boarding schools too.

“As we have seen in Canada, the truth will eventually emerge about what is buried on Indian boarding school grounds,” it adds. “A Congressional Commission will help ensure that accounts of Indian boarding schools – told by survivors, families, and presently undisclosed records – are preserved.”

Demands for reparations for Indigenous peoples take many shapes, ranging from acknowledgment and apology, to cultural revitalization, to financial compensation, to what’s called the “land back” movement to reestablish Indigenous sovereignty.

Canada has framed justice for Indigenous peoples around “Reconciliation,” including “94 calls to action,” or demands for policy change, issued by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In January, the federal government and 325 First Nations agreed to settle a class-action lawsuit for the loss of language and culture due to residential schools for $2.8 billion (Canadian; U.S.$2.08 billion).

In the U.S., more focus has also been placed on justice for Native Americans in the past decade. But it is the land that is seen as the key reparation for many Indigenous peoples. That demand ties directly to the residential schooling system, argues Taiaiake Alfred, a Kanien’kehaka author who wrote the upcoming book “It’s All About the Land.”

“If from the beginning you cap this process at an apology, or individual compensation, even if that includes some very worthy projects on healing and counseling and trauma, you’re still dealing with it only at the individual level,” says Dr. Alfred, who received C$10,000 for being an Indian Day School survivor. “The initial driving force for residential schools was to remove the coming generations of Indian people from their land so that it could be used by industry or settlers. And so it’s always about the land.”

Two years ago, the suspected unmarked graves of 215 children discovered at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in Kamloops, British Columbia, marked a pivot point for both individuals and nations.

“It brought everything to the head,” says Ms. Skidders, who knew her mother went to a residential school, but only then set out to learn the details. “It was in my head all the time and you just ... you can’t figure out what it is. And as horrible as it was, it helped to explain who we are and what we’ve gone through and where we are right now.”

The news of unmarked graves in Canada also spurred the U.S. to action. A month later, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna, launched the DOI initiative.

The first report from the investigation, released last year, details over 400 boarding schools the government operated, including “at least 53 burial sites,” which had the goal of cultural assimilation and territorial dispossession of Native people. The report is “only a first step,” its authors write, but it “can help begin a healing process ... from the Alaskan tundra to the Florida [E]verglades, and everywhere in between.”

One person pushing for an apology in the U.S., one that acknowledges guilt and punishment, is Mr. George-Kanentiio. He hopes the U.S. will go further than Canada, providing transparent access to records that helps paint a full picture of accountability. “The president issues an apology – and a commitment to justice. That’s what [former Prime Minister] Harper did not do,” he says. “No one ever asked us, what do you want? What would help your healing? ... I believe Joe Biden will do it.”

This story was produced as part of a special Monitor series exploring the reparations debate, in the United States and around the world. Explore more.