Why some Republicans are opting for conference calls instead of town halls

Loading...

A growing number of Republican lawmakers are opting out of town hall meetings this week, choosing instead to speak with their constituents in a less direct way.

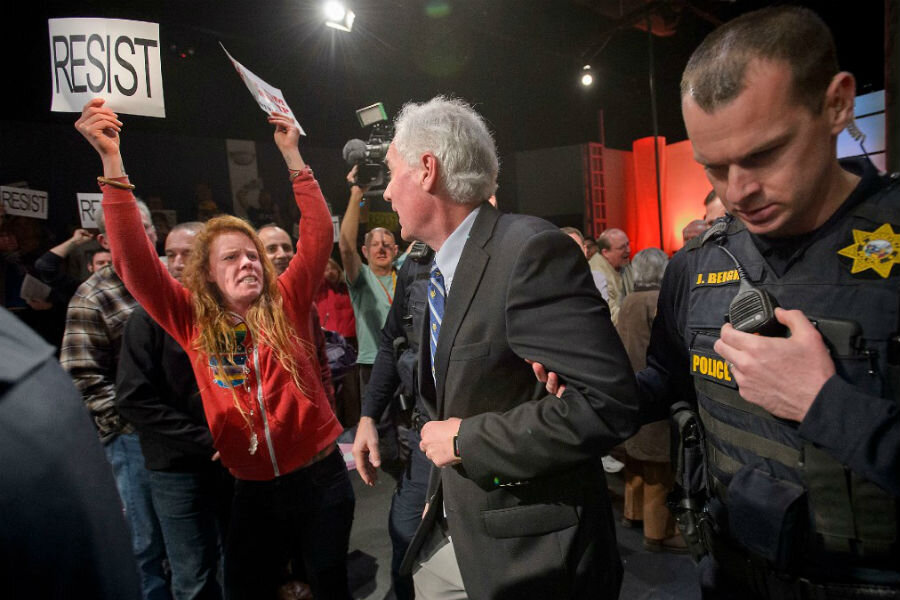

In response to a wave of anti-Trump activism that has resulted in the perceived "hijacking" of such public town hall events by protesters, many Congressional Republicans are ditching the traditional in-person appearance in favor of large conference calls with constituents, with in-person meetings limited to small sit-downs with individuals and community groups.

During these conference calls, dubbed "tele-town halls," questions are screened by aides, with no follow-ups, crowd reactions, or visuals. Those who endorse the strategy say it keeps question-and answer-sessions productive by eliminating disruptions from angry demonstrators, and is a necessary measure amid post-inauguration unrest. But critics say face-to-face interactions between lawmakers and their constituents are necessary for a healthy democracy.

"I like hearing divergent views, but I don't want to be baited into having an event that some outside group can just make a spectacle out of," said U.S. Rep. Tom MacArthur on Monday, when asked during a teleconference with constituents why he wasn't addressing them in person. Such events, he said, are frequently "highjacked."

In many ways, the phenomenon is an "uncanny reprisal of the 2009 birth of the tea party – but this time on the left," as Patrik Jonsson reported for The Christian Science Monitor on Wednesday:

In 2009, the Democratic playbook involved avoiding town halls and dismissing protesters as paid stooges. Then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D) famously said the protesters were not grass roots but fake “Astroturf.” A year later, tea party fervor reshaped Congress, with Democrats losing 63 seats in the House and five in the Senate. The Democrats have never recovered.

Today, the Republican playbook involves avoiding town halls and dismissing protesters as paid stooges. Utah Rep. Jason Chaffetz (R) called the protest that shouted him down at a recent town hall a “paid attempt to bully and intimidate.” Only 10 Republicans members of Congress are planning town halls next week, notes David Hawkings of Roll Call....

"One of the things we’re seeing in American politics right now is it’s easier to get people energized in opposition to things they don’t like than to get them energized to support anything their party or president is doing," says Alan Abramowitz, a political scientist at Emory University in Atlanta. "People are really angry and worked up, and I don’t think it’s going to stop. In some ways, this is even more organic than the tea party."

"Town hall meetings tend to be platforms for people to shout at one another and get angry at one another and leave more upset and disappointed and bent out of shape than when people came," U.S. Rep. Peter Roskam of Illinois told a Chicago radio station last week. "And the proof of that is just look at the national news."

Rep. Roskam noted that during his decade in Congress, he's only hosted one town-hall meeting, which he "didn't find ... particularly productive." Last year, he held 11 tele-town halls.

But many concerned constituents say events like these aren't enough.

"It’s the same reason people like to go to concerts instead of just listening to the radio or buying the album," activist Nancy Bea Miller told the Philadelphia Inquirer. "Looking someone in the eye, even if it's across an auditorium, really helps you judge the person, decide how sincere they are."

Some Republican lawmakers agree. U.S. Rep. Vern Buchanan of Florida told the Herald-Tribune that he will continue to host town hall events, despite the fact that "there's a lot of passion out there."

"We want to have town halls," Rep. Buchanan said. "We want to have it constructive. I want to get their input so I can better represent them."

"We are a democracy," he added. "People get a chance to weigh in."

In-person town hall events may be worth the risk, political analysts say, not just for the sake of democracy, but as a smart political move for the lawmakers themselves.

"Democracy is a messy thing, and this shows it – and it’s also a fragile thing," James Thurber, founder of the Center for Congressional and Presidential Studies at American University in Washington, told the Monitor. "That’s why members of Congress have got to get used to this and listen to the feedback or there will be consequences for them, electorally."