How a journalist used old and new techniques to investigate Trump charity

Loading...

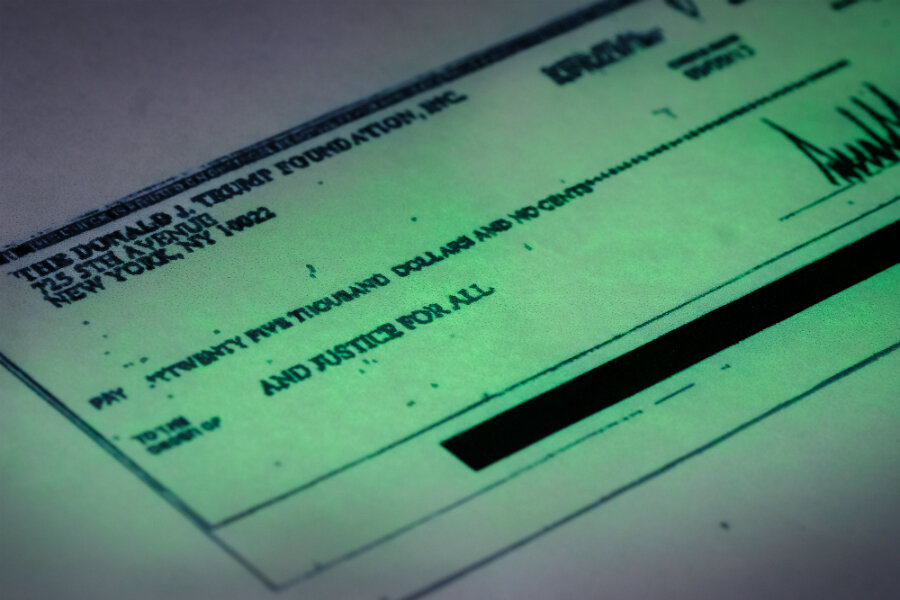

After persistent digging by Washington Post reporter David Fahrenthold revealed that Donald Trump's personal charity had been soliciting donations in New York without the proper registration to do so, the state's attorney general sent a letter to the foundation Friday ordering it to stop.

Mr. Fahrenthold, who has been described as "one of the journalism stars" of this election cycle, landed the scoop by combining tried-and-true methods with more novel approaches to investigate donations purportedly made by Mr. Trump.

By not registering with the state, the charity had avoided annual audits, including those to determine whether charity money was being used to benefit Trump or his companies.

While using spreadsheets or social media in the reporting process has grown increasingly common in recent years, Fahrenthold has managed to harmonize the two distinct tactics in a way that could signal an evolution in the way investigative journalists work.

"What David has done that is remarkable is that he has combined old-school techniques – basically, calling every foundation that Trump might have donated to – with new-school transparency on Twitter," Bill Adair, a journalism professor at Duke University, tells The Christian Science Monitor.

Fahrenthold, who has been working since March to make sense of donations made to and by the Donald J. Trump Foundation, has frequently tweeted about his investigation pre-publication, even sharing photos of his handwritten list tracking more than 300 nonprofits to which the foundation might have donated.

"That's not the way investigative reporting is usually done," Professor Adair adds. "Reporters don't usually show their work as they're doing it. More typically, they collect all the evidence, and then they confront the subject."

The unconventional approach, however, seems to be working.

"I had a really good experience with Twitter in May," Fahrenthold tells the Monitor.

After the Post could find no evidence to support Trump's claim to have donated $1 million to veterans groups – and the campaign declined to specify when or to whom the money had been donated – Fahrenthold began tweeting at the biggest, most social media-savvy veterans organizations he could find, tagging the candidate in each message. Trump criticized the media, then donated $1 million to a veterans group.

"That was a real success story for me," Fahrenthold says. "It seemed like it drew people into the scavenger hunt element of it. Readers got interested. Other journalists got interested. I thought, OK, there's maybe a way to replicate that for the broader search for all these millions of dollars of donations that he says he's given to other charities he won't tell us the details of."

Online, Fahrenthold's handwritten list takes the form of a polished, annotated table, thanks to Post designer Danielle Rindler. This table is a form of "structured journalism," like fact-checking site Politifact or murder-tracking site HomicideWatch, says David Caswell, the founder of StructuredStories Inc.

Structured journalism is "an umbrella term that refers to thinking of journalism as bits and pieces of information that can be mixed and matched in infinite ways," rather than a "one size fits all" report, as the Columbia Journalism Review defines it – but, like the method itself, its definition is still evolving.

Adair, who founded Politifact, takes a stricter view of structured journalism that excludes Fahrenthold's work, but the difference of opinion could be limited to terminology.

"The term 'structured journalism' is not really a crisp, hard term," Mr. Caswell tells the Monitor. "It's more, in my view anyways, a reflection of an attitude towards reporting or an approach towards reporting."

Unlike data reporting, where a journalist finds a story in a preexisting database, structured journalism entails the creation of a database through the reporting process, Caswell says.

"In the case of the Trump Foundation reporting, there's a bit of both going on there," he adds.

Fahrenthold says he searches his own database records every day, but he also relies on shoe-leather-reporting tactics as well. The tip about the foundation's incorrect registration, for instance, came from an unnamed law professor to whom he was referred by an attorney who declined to comment.

"I would never in a million years have figured that out on my own," he adds.

The impact of this reporting on the election remains to be seen, however. And it could be minimal, if the records Trump's foundation must disclose to comply with New York law lack buzzworthy news items of their own, according to Daniel Kurtz, a nonprofit attorney and former head of the New York State Attorney General's Office charities bureau.

"This could be a big deal, but it might be very trivial," Mr. Kurtz tells the Monitor. "No one will know until way after the election."