Why do Hawaiians want race-based elections?

Loading...

A group of Hawaiians are suing their state in federal court for preparing to hold elections that would serve only one race – the islands’ native population.

The justification for the race-based election? Everyone else is doing it.

Every other indigenous group in the United States has already has its own government. This is why, for example, US state and federal police need special certification to operate on Native American reservation land, and the tribes can opt out of daylight savings or state casino prohibitions if they choose.

The former US Sen. Daniel Akaka (D) of Hawaii, who retired in 2013, worked for more than a decade to give native Hawaiians the same self-government rights that Native Americans in the contiguous 48 states and Alaska already have.

The first step toward this goal came in 2011, when the state formally recognized the native Hawaiians. The state then created a Native Hawaiian Roll Commission to start making a list of eligible native Hawaiians who could elect delegates to a convention that would form a government with help from Nai Aupuni, a non-government organization.

The US Department of the Interior made a tentative plan for a formal relationship with whatever government the native Hawaiians set up.

In August, however, six state residents filed a lawsuit to stop the election. Two are non-native Hawaiians who cannot vote in the election, and two are natives who do not want their names on the voting list.

The other two simply disagree with the statement required for voter registration to "affirm the un-relinquished sovereignty of the Native Hawaiian people, and my intent to participate in the process of self-determination."

The state of Hawaii says it has no official involvement in the election, so the racial basis of the election is not unconstitutional. The lawsuit, however, points to a $2.6 million state contribution to the election process. The funding comes from the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, a state office that works to improve the lives of native Hawaiians.

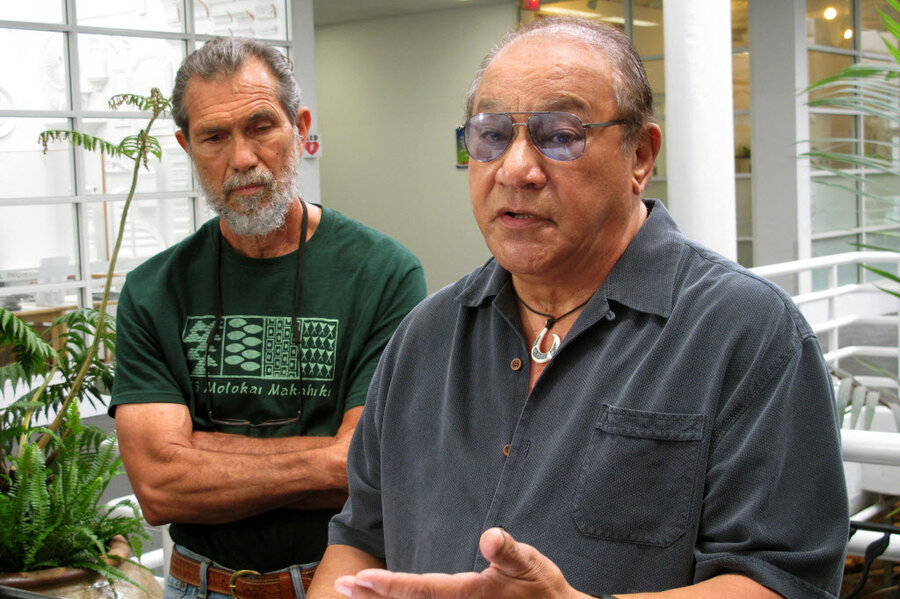

The hearing Tuesday focuses on the desire of the plaintiffs – the anti-election Hawaiians of the case – for the judge to make a preliminary injunction and stop the election, or at least stop people from registering to vote.

Nai Aupuni said stopping the process now would be the worst thing. In its own submission to the court, Nai Aupuni said Hawaiians have been waiting and working for this for more than 100 years, and the chance may not come again for another century.

This report includes material from the Associated Press.