California drought: Clock ticking on 17 communities' water supply

Loading...

| Los Angeles

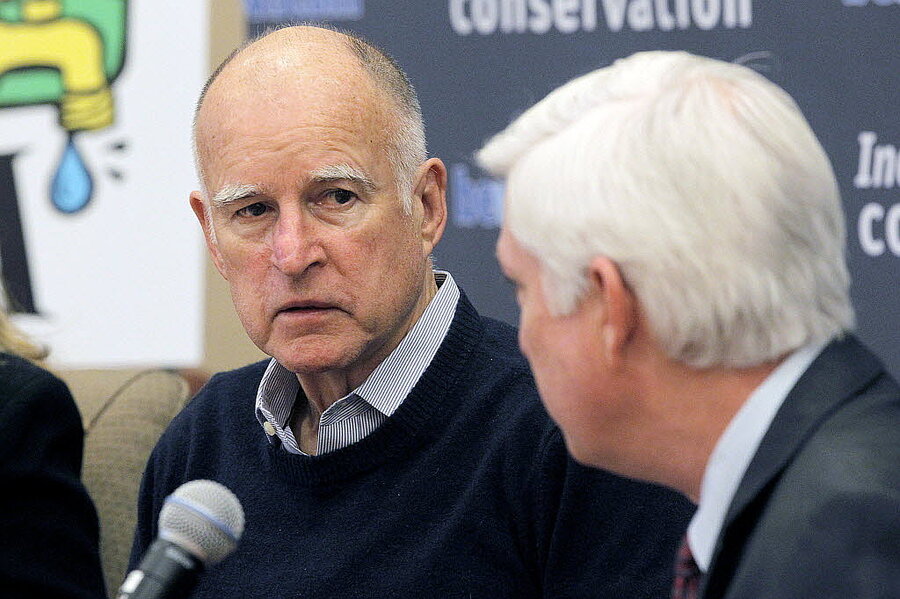

Gov. Jerry Brown met with Southern California water managers Thursday to plan further responses to the state’s worst drought on record. The latest sign of its severity was this week’s announcement from California’s Department of Public Health that at least 17 of the state’s rural communities are in danger of running out of water within 100 days.

Governor Brown declared a drought emergency two weeks ago and called for voluntary 20 percent conservation measures. On Thursday he dispensed tips to Los Angeles area residents: "Don't flush more than you have to, don't shower longer than you need to, and turn the water off when you're shaving or brushing your teeth.”

But, say experts, this water emergency is just one more sign of more extreme water challenges to come and requires broader and more far-ranging strategies.

The water emergency highlighted by the ticking clock on these 17 rural communities is “simultaneously painfully local and thoroughly global,” says David Cassuto, a professor at Pace Law School.

“Each affected city will have to adapt its conservation measures to its particular geography. Some towns can drill extra wells, some can impose draconian conservation measures, and some have no easy answers at all and will have to seek emergency help from elsewhere,” he says via e-mail.

These local emergencies underscore the national emergency of a worsening water shortage virtually everywhere, he says, and “the national emergency is but a microcosm of a looming global disaster.”

California’s economy stands to suffer, points out Jay Lund, director of the Center for Watershed Sciences at UC Davis. A third of the nation’s crops are produced in California’s Central Valley, with some nine million acres under irrigation. “We might see half a million acres go fallow in this drought,” he says, with thousands of jobs lost as a result.

We are currently seeing new droughts that stretch our ability to cope, given infrastructure that was built for a climate with fewer weather, and precipitation, extremes, says John Sabo, an ecologist and associate professor at Arizona State University who specializes in sustainability. As individuals, “we need to readjust our attitudes and refocus our lifestyle to embrace the reality of deep drought,” he says via e-mail.

“This means changing how we vote to invest in water efficiency projects. Water reuse and desalinization projects should be more carefully considered as parts of an integrated solution. At home, every drop counts,” he writes, adding that government incentives to replace turf and water inefficient appliances are also valuable.

Individuals cannot solve this problem alone, agrees Christiana Peppard, author of the recently published “Just Water” and a professor at Fordham University in New York. “It's a structural, systemic, societal issue – and so California has to get clear, fast, on what kinds of uses are renewable or not.”

This must be done at a range of levels: local, municipal, county, state, and region, she says via e-mail, adding that “water is no respecter of boundaries or human desires.”

In the 20th century, says Professor Peppard, “we made water work for us, partly on the assumption that supply was unending. In the 21st century, we have to focus on water as a finite, scarce resource – and learn to work with it.”

Water determines the fate of civilizations, she says, adding, “not the reverse.”

“This drought is different both in degree and in kind,” she says. The implications are “clear, present, and unavoidable.”

“Water wonks have known this for a long time,” she says, adding, “just as many Californians realized they were in a drought long before the governor declared it.”