Rebecca Sedwick suicide: Parents to blame for their bullying children?

Loading...

In the wake of 12-year-old Rebecca Sedwick’s suicide last month – in which authorities have alleged that relentless bullying, much of it online, played a significant role – the question of how to prevent cyberbullying attacks is reemerging.

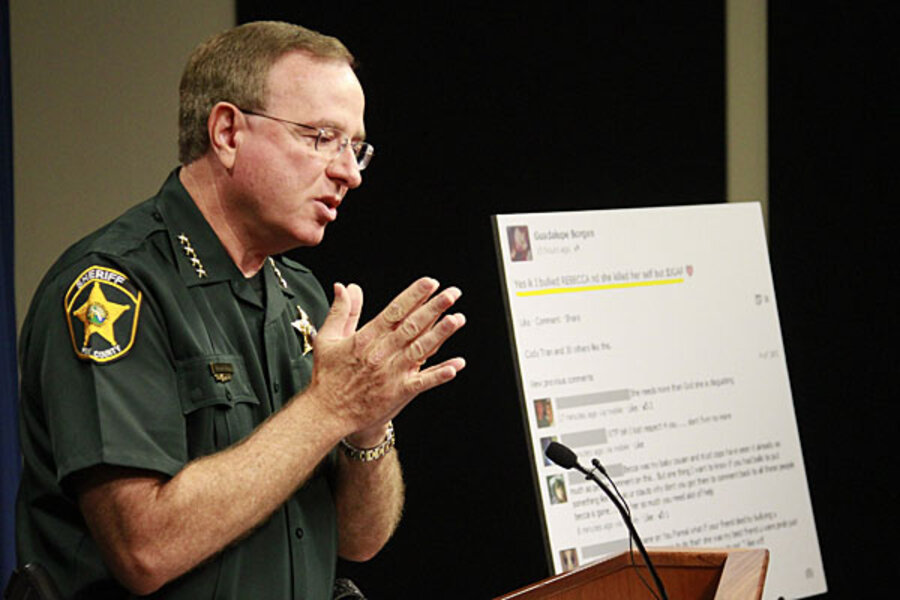

On Monday night in Florida, Polk County Sheriff Grady Judd arrested two of the girls, a 14-year-old and a 12-year-old, who he says were the worst offenders. And he has said that, if he can, he’d like to bring charges against some of the parents as well – though that may not be possible under current law.

The case is raising questions of culpability and responsibility in bullying. To what extent can bullies be held responsible for a suicide in which it certainly seems to have played a role? And who holds responsibility besides the bullies themselves? Their parents? School administrators? Peers who knew it was occurring but didn’t stop it?

“The laws are there, we just need to have a culture that tells us this is what’s right to do,” says Debbie Johnston, national legislative liaison for Bully Police USA, a group that works to get antibullying laws in place, and a Florida parent whose son committed suicide after relentless bullying eight years ago. “The problem is not the kids reporting, the problem is usually the adults who do not listen and follow up.”

In Rebecca’s case, Sheriff Judd has described the bullying as relentless and said Rebecca was “absolutely terrorized on social media.” She received messages, many of them through messaging applications like ask.fm and Kik, telling her to “drink bleach and die” and “go kill yourself,” and asking “wait a minute, why are you still alive?” The harassment continued despite Rebecca switching schools and interventions from her parents that included taking away her cellphone until they believed the problem had stopped and getting her counseling. On Sept. 9, Rebecca jumped to her death at an abandoned cement plant.

Judd has said in news conferences that he wasn’t planning to make arrests so soon, but that when the 14-year-old girl posted on her Facebook account over the weekend he felt he had to act. Her post said, " 'Yes, I bullied Rebecca and she killed herself but I don't give a ...' and you can add the last word yourself,” he said.

"We decided that we can't leave her out there. Who else is she going to torment, who else is she going to harass?” Judd said.

In an interview with ABC News, the 14-year-old’s parents said they believed their daughter’s Facebook account had been hacked and that she would never write something like that. A man who said he was the girl’s father told the Associated Press that “none of it’s true.”

But Judd described the 14-year-old as remorseless and “very cold” when she was arrested and criticized her parents for their lack of action.

"I'm aggravated that the parents aren't doing what parents should do,” Judd said.

When asked on NBC’s "Today" show about the likelihood of bringing charges against the girls’ parents, which he has said he would like to do, Judd admitted that right now, he can’t find criminal charges that are applicable.

“But if we can find a contributing to the … delinquency of a child we certainly would bring that charge, because I can tell you, the parents are in total denial,” Judd said. “They don’t think there’s a problem here, and that is the problem.…They even let her have her Facebook access after she bullied this child and after they knew it.”

Ms. Johnston, who helped write the antibullying law that Florida now has on its books, which is named after her son, says she believes parents often have huge culpability in bullying by their children.

In her son’s case, Johnston says, the cyberbullying took place over three years, and despite the bully’s parents being notified about his actions against her son and other students, they continued to give him access to the home computer and to allow the cyberbullying to go on unchecked.

“He killed my son as surely as if he crawled through the window, put a gun to his head, and pulled the trigger,” says Johnston. “And those parents loaded the gun that allowed him to do it…. They gave him the computer, gave him access, even when they knew for three years that he was hurting not just my child but others as well.”

The law Johnston helped get passed in Florida in 2008 is comprehensive, she says. It requires all districts to implement antibullying policies that require prompt investigation of allegations, create a mandatory reporting procedure, and outline consequences for violation of the policy. Victims’ families must be notified about what’s been done to protect their children – information Johnston says she couldn’t get when her son was being bullied, even though she was also a teacher in the school he attended – and bullies must be referred to counseling.

Still, it’s not clear what steps Rebecca's school took when notified about the bullying, and her mother has said they did not do enough. Johnston says she’s glad that Judd is prosecuting the two girls in this instance – who have been arrested on third-degree felony charges of aggravated stalking – in part because such cases, she hopes, can help set a precedent for the reach of the law.

“It’s been a long uphill battle to get schools and law enforcement simply to enforce laws already on the books to protect the civil rights of children,” she says.

Still, some cyberbullying experts say that real solutions to the problem may need to begin not with adults or law enforcement, but with peers and a changed culture.

In Rebecca’s case, as many as 15 other girls were reportedly involved in the bullying, and likely many more who were aware of it, says Nancy Willard, director of Embrace Civility in the Digital Age, which works to combat cyberbullying. And yet none of them seem to have stepped in to stop it.

“The critical issue is that these kinds of hurtful interactions are occurring in environments where adults are not present,” says Ms. Willard in an e-mail. “The current bullying prevention approaches are all adult-centric – adults make rules, supervise students, and punish those who violate the rules. School officials and parents are not making the rules for websites, they are not present in teen digital environments, and if they punish a student this can lead to uncontrollable digital retaliation. The players who we need to have get involved are the teens. So how do we do this?”

The challenges are numerous, Willard says: Many teens may fear negative consequences or embarrassment from stepping in, or incurring retaliation from the bully or the bully’s friends. And peer norms, she says, can be powerful. Teens may think others perceive that the person being hurtful is “cool” – even if that’s not accurate.

“We have to help them understand the high regard that teens hold of those who do step in to help,” Willard says. “We need to help students learn … how important it is to reach out to be kind publicly or privately to someone who is being hurt. How they can work as a team with several others to safely publicly tell someone to stop. How and why they should tell a friend who is being hurtful to stop. And when the situation has turned to high-risk that needs to be reported to an adult who can help.”

• Material from the Associated Press was used in this report