How to get high school dropouts into 'recovery'? Ideas bloom across US.

Loading...

| Boston

Cydmarie Quinones dropped out of Boston's English High School in May 2011 – senior year. "It was the usual boyfriend story," she says. "You put so much attention into your relationship ... that it kind of messes up the whole school thing."

Six classes shy of the credits she needed, she thought that she could skip getting a diploma and still find a college that would train her to be a medical assistant.

"I've been doing nothin' for a whole year," Ms. Quinones says. Actually, she's been running into walls – spending hundreds of dollars on in-person and online programs that made false promises to get her a high school credential. Meanwhile, her friends graduated and went on to college, including her boyfriend. This fall, she says he told her, " 'I can't have a girlfriend that didn't do nothin' in life.' " So she decided, "OK ... I have to do it for myself and for everybody else.... I have to get my diploma."

Nationally, about 600,000 students drop out of high school in a given year. And more than 5.8 million 16-to-24-year-olds are "disconnected" – not in school and not working. In 2011, governmental support (such as food stamps) and lost tax revenues associated with disconnected youths cost taxpayers more than $93.7 billion, according to Measure of America, an initiative of the Social Science Research Council, a nonprofit based in New York.

"Education has become so key to getting into the labor market [that] we call dropping out 'committing economic suicide' at this point," says Kathy Hamilton, youth transitions director for the Boston Private Industry Council, which partners with the school district to run the Boston Re-Engagement Center (REC), a hub for helping dropouts like Quinones complete their education.

Dropout prevention has been in the spotlight in recent years. But increasingly, school districts are also realizing that they can do more to bring young adults back into the fold.

It's called "dropout recovery," with districts deploying a host of strategies – from door-to-door searches for dropouts to alternative schools where people earn free college credits while taking their final high school courses. The efforts are taking place in dozens of cities ranging from Camden, N.J., to Alamo, Texas.

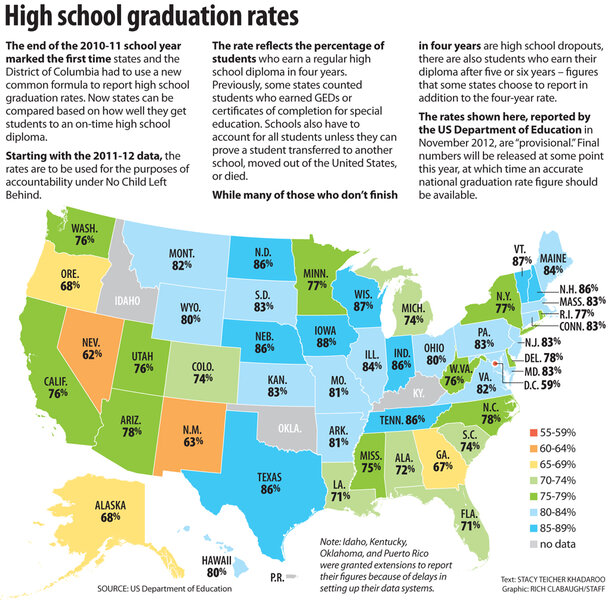

America has "long had a forgiving education system, where people can come back at any time to complete a diploma or finish a degree, but we haven't been structured to reach out and reengage youth who have dropped out," says Elizabeth Grant, chief of staff in the US Office of Elementary and Secondary Education. "As educators across the country saw more-accurate graduation and dropout numbers and recognized the size of the challenge, our school systems started to get more responsive."

The US Department of Education launched the High School Graduation Initiative in 2010 to support school districts doing dropout prevention and recovery work. Competitive grants were given out to 27 districts and two states, for a total of just under $50 million.

A personalized approach

At least 15 cities have organized stand-alone reengagement centers. They offer a one-stop, personalized case-management approach – bringing together schools, private businesses, workforce-development experts, and other partners to try to reconnect young adults with a promising future.

Since 2008, New York City's centers have reenrolled about 17,000 students, and the centers in Newark, N.J., have brought back 3,900, according to the National League of Cities.

Staff members at Boston's REC listen to each student's story, share struggles from their own school days, help them find the right school or alternative program to fit their needs, and stay in touch once they've reenrolled.

That's what won the trust of Quinones. In November she started coming every weekday to take online credit recovery courses at the REC, a bare-bones set of offices and computer labs with inspirational posters.

In just a month – keeping normal school hours, though that's not required – Quinones finished four courses and is on track to earn her diploma in February. Although she feels "stuck" in geometry, a teacher is on hand to guide her.

"In high school, teachers never really sat with me.... Having teachers take out their time ... to go through one problem for four hours, that means a lot," she says.

The REC "has expertly directed students toward options that are best suited to their needs, rather than falling into the habit of putting them back in the school where they were previously unsuccessful," says Chad d'Entremont, executive director of the Rennie Center for Education Research & Policy in Cambridge, Mass.

Since 2010, the REC has re-enrolled more than 1,300 students. About 7 out of 10 persist for at least a year. The tracking system for the total number of graduates is still being developed, but at least 160 earned their diploma within about a year, Ms. Hamilton says, and she predicts many more will do so over a longer time frame.

Dropouts are a diverse and difficult group to get across the finish line. About 1 in 5 says he or she lacks parental support, and another fifth are parents themselves, according to the 2012 High School Dropouts in America survey by Harris Interactive. Other reasons for dropping out include mental illness, the need to work, too many school absences, and uninteresting classes. Some dropouts have spent time in prison or on the streets.

Settings that offer flexible schedules and sustained personal attention are often required to help them master the skills they need.

"I'm always very honest with them: 'It's going to be tough, but it doesn't mean it's going to be impossible. And I'm going to help you envision yourself with a cap and gown a year from today, or two years from today,' " says Carolina Garcia, a dropout recovery specialist at Boston's REC.

An 'early college' approach

In Texas, an "early college" approach to dropout recovery is gaining national attention.

At least 10 districts are motivating dropouts to come back not just to finish high school, but also to take community-college courses free of charge – sometimes enough to earn an associate's degree or a training certificate.

The most notable is the Pharr-San Juan-Alamo district (PSJA), where 90 percent of the population is Hispanic and about a third is low income.

When Daniel King became superintendent there in 2007, he faced a dropout rate of about 18 percent. Nearly half the dropouts that year were seniors – 237 of them. "I felt I needed to immediately do something ... [because] the more time that went by, the harder it would be to find them and reengage them," he says.

In a matter of weeks, he had teamed up with South Texas College to launch the College, Career, & Technology Academy (CCTA) for 18-to-26-year-olds – in leased space in a former Wal-Mart.

He put up banners around town with the message: "You didn't finish high school. Start college today." That, combined with a door-to-door search for students who had dropped out, resulted in 223 of those seniors coming back to school.

By May 2008, about 130 had earned their diplomas. To date, more than 1,000 students have graduated from CCTA, more than half of them with college credits.

Along with core academic courses, former dropouts start with a college-success course that solidifies their study skills. Then they move on to career and technical-education courses such as welding or medical terminology.

The state allows both the school district and the community college to receive per-pupil funding, so the education at CCTA is free to students. Texas is also unique in funding high school students up to age 26. (Most states stop at around 21.)

"Before I came to this school, I had zero drive in me," says CCTA student Edgar Rodriguez. He was out of school for a semester and a summer while being "reckless" and "irresponsible," he says.

At CCTA, teachers tutored him for exams that had previously stumped him. The college-success class, taught by his former English teacher, inspired him to want to pursue teaching.

During a recent visit to an elementary school, Mr. Rodriguez shared a story and Web page he had created. "I had never been on that other side of the table where I was the one giving the presentation. I loved the atmosphere," he says. "I knew then, that's what I want to do."

As a fallback, he's taken medical-billing classes. His older brother was the first in the family to graduate from high school, he says. "Now I hope to lay down the next standard of going to college," says Rodriguez, who graduated last month.

Dropout recovery has also inspired more-effective prevention. Most PSJA students now have access to college-level courses while still in high school, which keeps them motivated. And students falling behind in the regular schools can move into "transition communities" where they get more individualized attention until they catch up.

The district's dropout rate is dramatically down – from 18 percent in 2006 to just 3.1 percent in 2011. (The state average was 6.8 percent in 2011.)

Superintendent King was able to expand the early-college approach because "he made the case [that] if these [former dropouts] can go to college, why can't we do this for all students?" says Lili Allen, who is helping a network of districts replicate PSJA's approach.

"It was a smart and counterintuitive strategy," adds Ms. Allen, director of Back on Track Designs at Jobs for the Future, a nonprofit based in Boston.