Economic toll of Sandy: Damage second only to Katrina?

Loading...

Economic impacts of superstorm Sandy are just starting to come into view, but what's clear is that they're big.

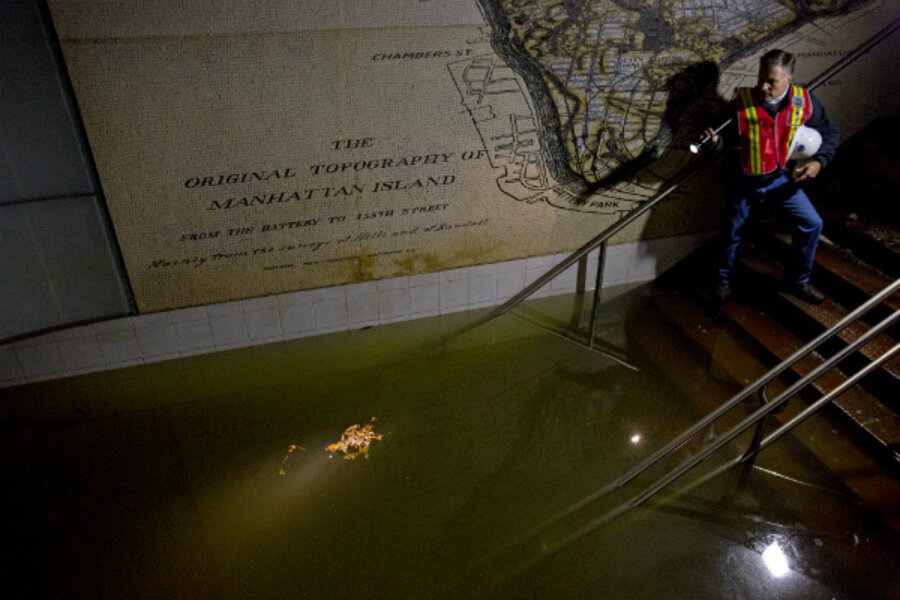

The nation's economic capital, New York City, has been hobbled by electricity outages, floods, and damage to its massive subway system. From flooded Hoboken to wave-battered Atlantic City, the storm caused extensive structural damage in cities and towns along the coast of New Jersey. And across a multistate region, consumer activity was sidelined at least briefly by Sandy's winds, rains, and snows.

One firm that specializes in storm damage forecasting, EQECAT, raised its Sandy estimate to total economic damage of $30 billion to $50 billion, with about one-third of that being insured losses claimed by homeowners and businesses. For reference, $50 billion is about 0.3 percent of one year's gross domestic product (GDP) for the US.

If accurate, that estimate would put Sandy behind hurricane Katrina in 2005, but ahead of other major US hurricanes.

The investment firm Morgan Stanley cites data from the National Climatic Data Center, which puts the economic damage of Katrina at $146 billion, when measured in today's dollars. Pending a final tally from Sandy, the second-ranking hurricane since 1980 is Andrew, which in 1992 did damage of $44 billion in today's dollars.

Wherever Sandy ends up, it will be high on the list of major storms. Yet it's tricky for economists to predict how Sandy will affect US economic growth.

The damage is large. The impact on families and businesses in the hardest-hit areas is large. But by itself, that doesn't mean Sandy will automatically put a big dent in GDP for the current quarter. To some extent, the losses from the storm are offset by a flood of a different kind – the inflows of disaster aid, insurance claims, and "catch-up" spending by consumers who had to delay purchases due to the storm.

"The disruption to business activity ... probably occurred early enough in the quarter to be offset by rebuilding activity and replacement demand for things like automobiles," writes David Greenlaw, a Morgan Stanley economist in New York. So far, Sandy isn't prompting the firm to change its GDP forecast.

"Most estimates suggest that Katrina subtracted between 0.5 and 1.0 percentage points from GDP growth during the second half of 2005 with a corresponding boost to activity in 2006," he says in his analysis. Striking right at the flood-vulnerable city of New Orleans and near major oil refineries, Katrina affected US energy production for months and triggered some 200,000 job losses.

Mr. Greenlaw says he doesn't expect "significant permanent job loss" or energy impacts in the wake of Sandy. "On the other hand, it seems like Sandy caused significantly more damage to transportation infrastructure than Katrina."

And in terms of damage to residential properties in the affected region, Sandy's scale may be comparable to the 300,000 homes damaged or destroyed by Katrina, the Morgan Stanley economist says.

Other firms are also churning out preliminary assessments.

The forecasting firm IHS Global Insight estimates that Sandy could reduce GDP growth by 0.6 percentage points in the October-December quarter, the Associated Press reports.

That's at the high end among estimates, while some other forecasters see Sandy's effect on GDP as potentially minimal.

Mark Zandi at Moody's Analytics wrote Wednesday that, for all its grim statistics, the storm may not push fourth-quarter GDP up or down.

Economic output in the region between Greater New York City and Washington totals about 15 percent of America's GDP, Mr. Zandi figures. He then reckons that the storm may have caused about two days of lost output in the region, plus perhaps an equal amount ($20 billion) of property damage, much of which will be repaired by the end of the quarter.

"Fortunately, major facilities such as sea and airports, rail and road systems, oil refineries and cell towers appear not to have been significantly damaged," Zandi said.

Economist Mark Vitner of Wells Fargo estimates that GDP "will likely be reduced by 0.1 to 0.3 percentage points in the fourth quarter." He predicts a similar sized gain in the first quarter of 2013, thanks to Sandy-related rebuilding efforts.

Mild estimates of GDP impact don't mean the storm is harmless for the economy. The money spent on repairing homes, rescuing flood-stranded people, and rerouting airplanes represents dollars that could have otherwise been spent in other ways.

In his report, Mr. Vitner warns that Sandy may result in losses of uninsured property that are "on the high side relative to Hurricane Irene and other storms," because a sizable share of water damage came in areas where owners don't typically carry flood insurance.

In many ways, viewing the storm's impact through the lens of GDP is misleading. Loss of property has a real impact on people's financial well being, yet those losses don't directly subtract from GDP. (Homes, furniture, and the like were part of GDP when they were first produced.) But cleanup and repair spending does add to GDP.

Still, measuring Sandy's effect on US growth is important, because the economy was in a vulnerable position before the storm struck. Its current pace of 2 percent annualized growth is weak, considering the high number of unemployed Americans and what economists see as looming "down side risks." Those risks include the expiration of major tax cuts at year's end, which are poised to affect consumers if Congress doesn't act, and potential challenges in the global economy as European nations grapple with debt burdens.

As October rolled into November, much of the East Coast was getting back to a semblance of normalcy.

To give just one indicator: Airline travel in the region had performed a u-turn from shutdown toward full restoration of service. On Nov. 1, even flood-saturated LaGuardia Airiport was welcoming planes back on its runways.

But the storm's ongoing effects are equally visible.

New York City Comptroller John Liu told Reuters that in the days immediately following the storm, "economic activity is down to about 20 percent of usual. It's a huge drop."

Still, with each day the "Sandy effect" should diminish, in a city that typically sees $2 billion in economic activity per day. "Based on past history, most of that economic activity is not completely lost, it's just postponed," Mr. Liu said. "We don't believe the permanently lost economic activity will exceed $1 billion."

Households and businesses that suffered uninsured storm damage to their property may get financial help from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. And Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have offered a 90-day forbearance program, so affected families may get to reduce or postpone payments on mortgages that the firms own or guarantee.