Obama invokes executive privilege to protect Eric Holder: Can he do that?

Loading...

| Atlanta

The standoff between President Obama and the Republican-led House of Representatives moved into uncharted territory Wednesday when Mr. Obama claimed executive privilege for the first time in his presidency to block a House investigation into a botched federal gun-running sting called “Fast and Furious.”

Under Fast and Furious, some 2,000 weapons were allowed by the United States to be “walked” by straw buyers into the hands of Mexican drug cartels. Whether the operation was the result of rogue ATF agents or approved by the executive branch is what an 18-month investigation spearheaded by Rep. Darrel Issa (R) of California claims it has so far been unable to verify.

A separate inspector general investigation ordered by the president has yet to yield a summary of how the operation came to be approved and put into effect.

Painted by Democrats as a political witch hunt, the 18-month probe, Republicans say, was undertaken primarily on behalf of slain border patrol agent Brian Terry, who was killed in December 2010 by drug runners who were carrying two Fast and Furious rifles. At stake are some 80,000 documents that the Department of Justice does not want to release, saying they include privileged information, a decision that sparked Wednesday’s contempt hearing by the House Oversight Committee and the president’s decision to freeze the documents.

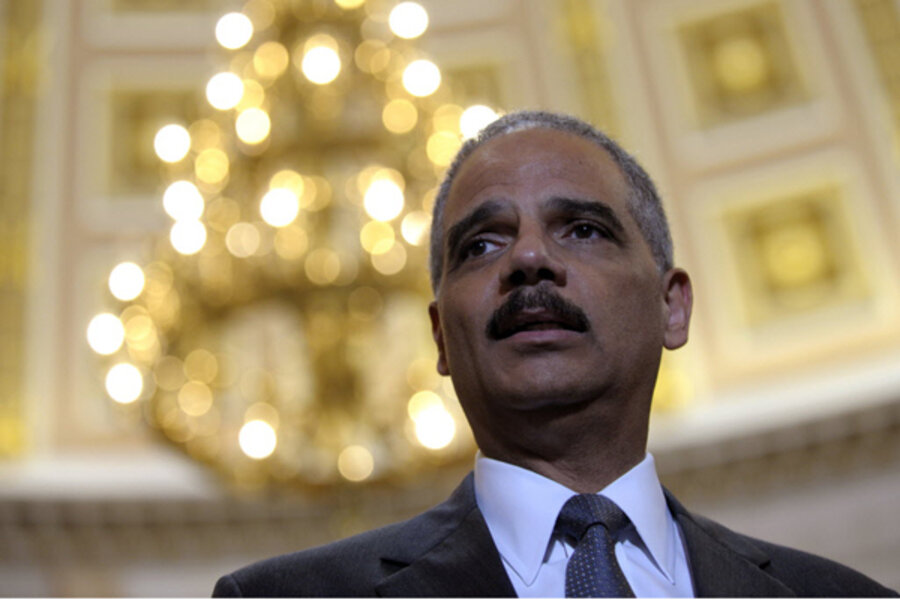

Sharing the “Fast and Furious” documents with Congress “would raise substantial separation of powers concerns and potentially create an imbalance in the relationship” between Congress and the White House, Attorney General Eric Holder wrote to Obama on Tuesday. Letting the committee have the documents “would inhibit candor of such Executive Branch deliberations in the future and significantly impair the Executive Branch’s ability to respond independently and effectively to congressional oversight."

The president’s move raises questions about whether the documents are actually covered by executive privilege, and also whether it is an admission by the White House that it knew more about the operation than it has let on.

“All presidents tend to claim executive privilege from time to time, in large part because, in order to function effectively, the executive branch needs to be able to keep deliberations confidential and people have to be able to give unbiased advice and be candid without worrying that what they said is going to end up in the papers,” says Kermit Roosevelt, a constitutional law professor at the University of Pennsylvania. “On the other hand, there’s always concern that the executive is asserting privilege in order to conceal information that’s not confidential, but embarrasing, so it’s a hard balancing act.”

While the constitutional game of chicken between the White House and House Republicans carries heavy political risks for both sides, the president’s order has at the very least raised the long-running and complex Fast and Furious debate to a new level only months before a presidential election, putting Mr. Holder in the greatest bind of his political career. If approved by the House, an eventual contempt charge could mean a criminal investigation that could land Department of Justice officials in jail if it turns out they lied or tried to cover up their knowledge of the operation.

Investigators have tied several high-ranking Justice officials to wiretap applications for the Fast and Furious operation, suggesting that officials may know more than they’ve let on about what happened. Moreover, in the past 18 months, Holder has had to backtrack statements about the DOJ’s role at several points and has had to retract one letter that categorically denied that the ATF, a Justice bureau, ever let guns “willfully” walk into Mexico. Those admissions of error only piqued Republicans on the House Oversight Committee, who met with Holder privately and unsuccessfully on Wednesday to discuss a way to head off a contempt vote.

Holder had proferred Republicans a quid pro quo, reported Congressman Issa, the Oversight Committee chair: In exchange for ending the investigation, Holder would not release the documents, but would brief investigators on specific documents they were interested in. Opening Wednesday’s hearing, Issa said, “We need the Department of Justice to cooperate, but so far cooperation is not forthcoming.”

Democrats said Holder, who has testified over a dozen times on the Fast and Furious scandal and has apologized to Mr. Terry’s family, has acted in “good faith”; while the Oversight Committee is holding Holder “to an impossible standard,” said Rep. Elijah Cummings of Maryland, the committee’s ranking Democrat.

The executive order left the committee hearing in disarray, as Republicans pondered Wednesday how to proceed. If the committee approves a contempt order, it would go to the House for ratification. If approved by the chamber, the contempt order would spark a criminal investigation.

Executive privilege is usually reserved for matters of national security, under which the government’s efforts at controlling drug-running border gangs could fall. It also is used for White House matters and correspondence.

The White House says it applied the same standards as the Bush and Clinton White Houses did in claiming the executive privilege (Bush claimed it six times; Clinton. 14). In this case, a White House spokesman explained, the White House is concerned about releasing privileged communication between the Department of Justice and White House political officials that took place long after the fact, when the administration was trying to weigh its response to the scandal.

Republicans, however, had another take-away, saying that the president has now inserted himself into an effort where critics claim the administration is trying to protect its political appointees, including Holder, while possibly covering up not just a matter of national and international concern but a program that may have involved US officials breaking the law.

“This is now the president saying, ‘You can’t have these documents,’ to Congress, and that takes the dispute to a different level and puts the president right in the middle of it,” Weekly Standard editor Bill Kristol told Fox News.

While the legal and political impacts of the president’s decision are far from certain, the move, for the moment at least, seems to bolster what had become a flagging Congressional investigation that even Republicans feared would appear purely political and could damage the Republicans’ focus on the economy ahead of the election.

“Now the White House is saying that something is privileged that they previously denied existed, all of which means that this House investigation is arguably, though not obviously, legitimate,” says Michael Munger, a political scientist at Duke University, in Durham, N.C. “The Republicans have been impatient in a public sense and highly critical in a political sense, and I think that they’ve just made the president mad.”

But the confrontation has now moved to a new, somewhat unprecedented level, says Mr. Munger, for a presidency that has previously pushed the bounds of presidential power. “It is absolutely a constitutional showdown: an assertion of privilege to be able to ignore a constitutional order by the Congress,” he says.