Beyond Stuxnet: massively complex Flame malware ups ante for cyberwar

Loading...

Stuxnet move over. Cybersecurity researchers on Monday announced the discovery of Flame, a piece of malicious software that one firm has called "arguably ... the most complex malware ever found."

At this early stage of analysis, only a few of Flame's functions are understood, reports Kaspersky Lab, the Moscow-based cybersecurity company that uncovered it. Because of Flame's size and complexity, it could take years to unpack completely what the program can – and has – done, experts add. [Editor's note: The original version of this story misstated where Kaspersky Lab is based.]

From what is known now, however, Flame can spread via a USB drive, a Bluetooth device, or other machines on a network. In affected machines, it can wait for certain software programs of interest to run, then take screenshots, turn on the internal microphone to record conversations, and intercept e-mail, chats, or other network traffic. It can package these data, encrypt them, and send them off to designated command-and-control computers worldwide.

"It pretty much redefines the notion of cyberwar and cyberespionage," writes Alexander Gostev, head Kaspersky's Global Research and Analysis Team, in his blog.

Kaspersky found that Flame has been snaking through computer networks – predominantly in the Middle East – for at least the past two years, but possibly longer. The way it works and what it does suggests that Flame was made by a nation-state, experts say, and only four candidates have the technical know-how to create such software: the US, Russia, China, and Israel.

"Flame can easily be described as one of the most complex threats ever discovered," writes Mr. Gostev. "It’s big and incredibly sophisticated."

In fact, at 20 megabytes, Flame is about 20 times bigger than the Stuxnet digital weapon that wreaked havoc on Iran's nuclear centrifuge fuel-enrichment program around 2009.

Like Stuxnet, Flame has been deposited – nobody knows just how – on a few thousand computers across the Mideast, meaning that it is highly targeted. Stuxnet's key flaw was that it spread far too broadly – to an estimated 100,000 machines around the world and blew its cover as a result. Flame's creators – apparently some government with a keen interest in Iran, the Palestinian West Bank, Hungary, and Lebanon – may have tried to learn from that misstep.

While Flame's internal structure allows it to spread via a USB drive, Bluetooth device, or network, it is programmed to prevent spreading indiscriminately.

"While its features are different [from Stuxnet], the geography and careful targeting of attacks coupled with the usage of specific software vulnerabilities seems to put it alongside those familiar ‘super-weapons’ currently deployed in the Middle East by unknown perpetrators," Gostev writes.

Another cybersecurity company, Symantec, reported Flame popping up in Austria, Russia, Hong Kong, and the United Arab Emirates, too. Its researchers cited the "modular nature of this malware suggests that a group of developers have created it with the goal of maintaining the project over a long period of time; very likely along with a different set of individuals using the malware."

In tech-speak, Flame acts like a "worm," meaning it spreads by itself without the need for human intervention, opening up clandestine channels for moving stolen data out of the network back to its handlers and receiving updates and new spy modules that will help keep it effective for years.

Symantec reported that Flame's software allows its authors to "change functionality and behavior within one component without having to rework or even know about the other modules being used by the malware controllers."

Flame was only discovered by experts at Kaspersky Labs when they were called in by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) to look into another still unknown, destructive malware program that had deleted data on computers in Western Asia. Kaspersky then discovered previously unrecognized Flame files, which had been sitting in Kaspersky's own databases for years.

Kaspersky says there's little doubt a nation-state built Flame. Not only is it enormously complex, but its focus is on espionage instead of the quick payoff typical of operations by cybercriminals.

One of the ITU partners in the investigation agrees with that assessment. CrySyS Lab, based at Budapest University of Technology and Economics in Hungary, released its own analysis of Flame, which it calls "sKyWIper."

"The results of our technical analysis support the hypotheses that sKyWIper was developed by a government agency of a nation state with significant budget and effort, and it may be related to cyber warfare activities," CrySys concludes. It is "certainly the most sophisticated malware we encountered during our practice; arguably, it is the most complex malware ever found."

Flame may, in fact, be related to Stuxnet and another famous malware program known as Duqu, which experts say were probably developed by the same government team, although they say that's only a guess based on a couple of superficial technical similarities among Flame and others.

“We would position Flame as a project running parallel to Stuxnet and DuQu,” Kaspersky Labs said in its blog post Monday, suggesting that Flame would be a fallback in case Duqu was ever found.

For now, researchers acknowledge that much of Flame remains a mystery – as do parts of Stuxnet. Buried inside Stuxnet, for example, the file name Myrtus continues to provoke speculation.

Likewise, buried deep in Flame's code are file names that include: Boost, flame, flask, Jimmy, munch, snack, spotter, transport, euphoria, headache. Add to that list an entire barnyard of other cryptic file names buried even deeper: Gator, goat, frog, microbe, weasel, and Beetlejuice.

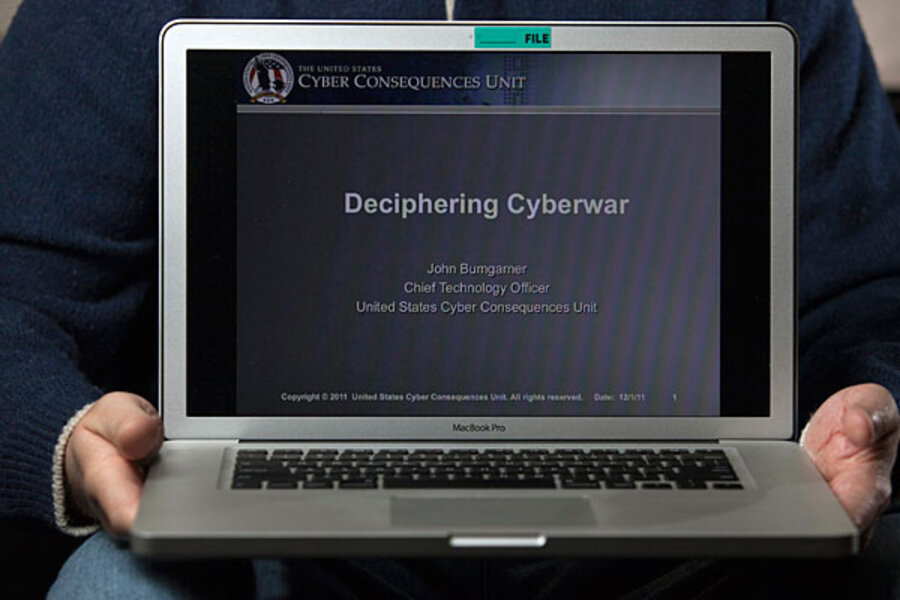

"We cannot conclude at this early stage that this thing [Flame] is designed strictly for espionage," says John Bumgarner, research director for the US Cyber Consequences Unit, a nonprofit security think tank that advises government and industry. "There's a likelihood it has other components to it that might have been designed to conduct sabotage. We just don't know yet what it can do."