Japan nuclear crisis eclipses Three Mile Island, nears 'Chernobyl league'

Loading...

Resolution of Japan's nuclear crisis hangs on the decisions – and actions – of about 50 remaining workers, laboring amid intense radioactivity and smoke, as they try to prevent the six-reactor Fukushima I plant from becoming a nuclear mess to rival the Chernobyl disaster, according to US nuclear experts monitoring the situation.

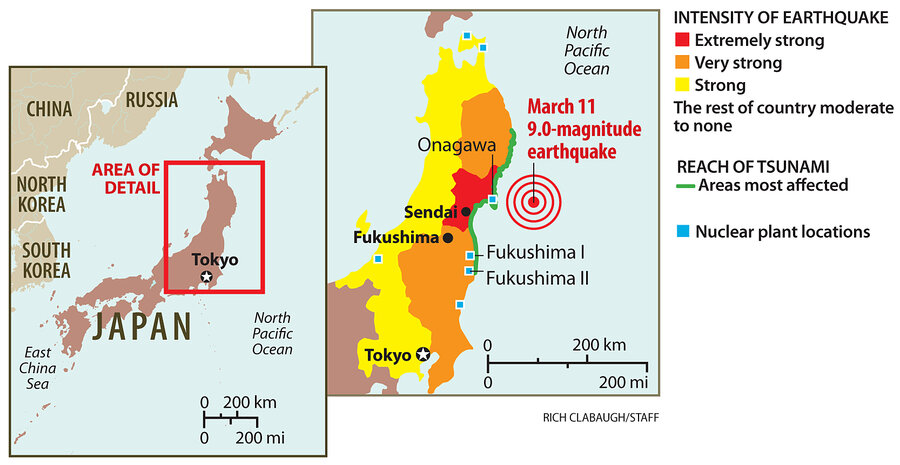

A spike in radioactivity at the site on Monday led authorities to send to safety most workers at the plant, which is 150 miles north of Tokyo. If the remaining few dozen personnel using just fire hoses are unable to keep three "hot" reactors – plus six pools containing spent fuel rods – cool, a meltdown would soon occur, these experts say. About 30 tons of water boil off the reactors each hour and must be replaced to prevent the reactor cores from melting down.

"This is definitely in the Chernobyl league now," says Frank von Hippel, a nuclear physicist at Princeton University. "If the reactors go, that's bad, of course. But the real concern at this point is if those ... spent-fuel pools catch fire. There are many Chernobyls' worth of radioactive material in there."

Radiation levels at the Fukushima I plant spiked briefly on Monday to more than 1 million times background radiation, before subsiding Tuesday to lower but above-normal levels, according to Edwin Lyman, a nuclear physicist and reactor-safety expert with the Union of Concerned Scientists in Washington. All but about 50 of 800 workers at the plant were told to leave, according to Japan Broadcasting Co.'s NHK World website.

The International Atomic Energy Agency on Tuesday raised its evaluation of the Fukushima emergency to a Level Six – a notch above the 1979 Three Mile Island partial meltdown, but still two notches below the 1986 Chernobyl accident in the Ukraine, which ranked an eight on its scale.

The head of France's Nuclear Safety Authority, Andre-Claude Lacoste, also characterized the situation in Japan as still less serious than the Chernobyl disaster but worse than the partial core meltdown at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania. "We are now in a situation that is different from yesterday's. It is very clear that we are at a Level Six," the ASN president said at a news conference in Paris.

Systems at the plant no longer provide any cooling function, say Japanese authorities. All of the cooling for the three endangered reactors (three others are in cold shutdown) and six spent-fuel pools is from fire hoses. Teams have been alternately venting radioactive steam and then injecting water into each reactor in a bid to cool it down.

At the current rate, the cooling of the reactors must continue for weeks, Dr. von Hippel and others agree. If rising radioactivity at the site or mechanical failure prevents these workers from continuing to cool the reactors steadily, meltdown becomes likely.

The good news so far is that most of the cesium 137 and iodine 131 – dangerous radioactive isotopes from each of the reactors – have been captured in "suppression pools," a type of filtering system beneath each reactor, von Hippel says.

The bad news is that if just one reactor core melts, it is likely to melt through the steel containment vessel and could easily drop into this highly radioactive pool of water. That could cause either an explosion or a rapid vaporization, releasing all the highly radioactive elements to go with the wind, says von Hippel. At two reactors, the secondary containment systems – the concrete buildings surrounding the reactors – were destroyed in earlier explosions.

Cesium 137 blowing on the wind made the area around the Chernobyl site, equivalent to half the size of New Jersey, from being inhabitable, even today.

Von Hippel and Dr. Lyman both say a critical issue is keeping water from boiling off in the six spent-fuel pools. A fire at the spent-fuel pool for the plant's No. 4 reactor was extinguished Monday, but radiation spiked afterward.

Though water is evaporating from these pools more slowly than from around the reactors, long-term damage from the Fukushima crisis may hang less on the reactors and more on whether the spent-fuel pools remain intact.

Temperatures in the No. 5 and No. 6 spent-fuel pools seemed to be rising, Yukio Edano, chief cabinet secretary and government spokesman, said in a press conference on Tuesday. While water in these large pools is unlikely to evaporate completely soon, workers are finding it hard to reach them because the water is so hot, a spokesman for Japan's Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency, which oversees nuclear plants, told The New York Times.

"Where the fire took place in the No. 4 pool, there is essentially a whole core's worth of fuel," says Lyman. "The problem is, they can't rule out whether it's boiling right now. There just hasn't been any conclusive information. But they have to keep these pools covered – and at the same time keep the reactors cool."

In the meantime, emergency workers may have to vent the reactors and pour in water "for weeks and weeks," he says. "I hope they can sustain that."