America's Job No. 1: A better employment rate

Loading...

The 9.6 percent unemployment rate is Issue No. 1 for voters heading into the congressional elections next month. America has about 7.8 fewer million jobs than it did in 2007. To put it more starkly: Total employment has fallen to 1999 levels, even though today's workforce is much larger.

In poll after poll, Americans say the economy and job creation are the nation's most urgent priorities.

Here are some answers to questions about how to do that, what policies could be tried, and what the stakes are.

If the recession ended in June 2009, why is unemployment still so high?

Two factors may be playing a large role: high household debt and a shift in the way many employers think about hiring.

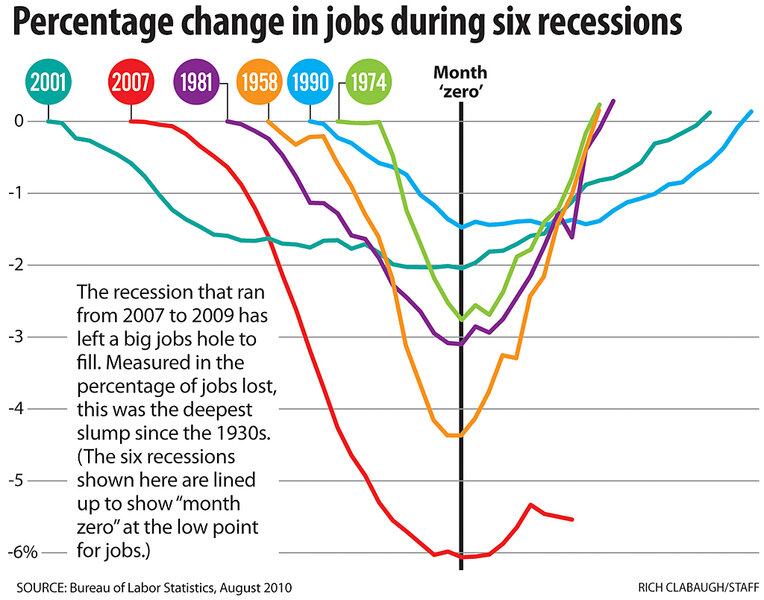

In decades past, recovery after a deep recession was often fairly rapid as consumers revived and employers rehired. After the 1981-82 recession, the number of jobs lost during the slump was regained in just a year.

What's different today is that the recession was rooted in a severe credit crisis. (In 1981, by contrast, a major factor was tight money policy.) Millions of consumers have high mortgage debt and have seen a plunge in the value of homes and investment portfolios. So consumers are spending less, while defaults on debt make banks less able to lend.

In such a climate, economic rebounds are typically slow. Because consumer expenditures are the fuel for the nation's economic engine – accounting for two-thirds of gross domestic product (GDP) – tepid demand makes employers cautious about hiring. Plus, the decision to add a worker is a bigger deal than it used to be. One reason: Health-care costs are rising faster than inflation, and the weak economy makes it harder for firms to cover those costs by raising product prices. Another factor: It has become easier to outsource jobs overseas in recent years.

Finally, as economist Arnold Kling argues, creating a job is an act of investment that often pays off only after a long wait. Forget the factory-floor model, in which demand picks up and workers are hired for a new shift. Given the growing automation of routine production work, new jobs often stem from corporate efforts to develop some new product, market, or capability.

Mr. Kling argues in a recent publication by the conservative American Enterprise Institute that, in jobs such as lab research or social-media marketing, "the return on an investment in workers may take as long ... to realize as the return on investment in a machine."

Whether for these or other reasons, the United States has a deep jobs hole to fill.

"What we need is millions of jobs in new industries which are highly paid, which are highly differentiated" from global competitors, says Robert Ackerman, a venture capitalist in California.

How does current unemployment compare with past cycles in the US, and those of the rest of the world?

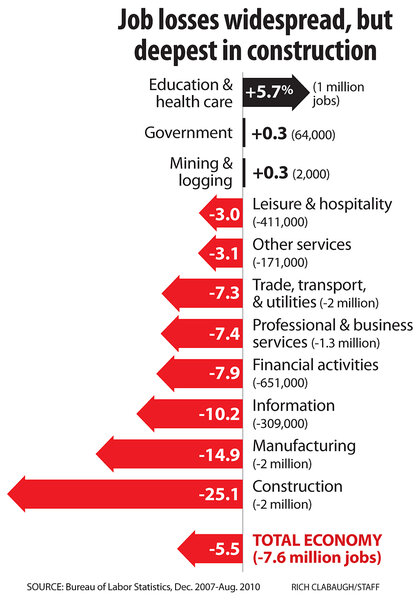

The loss of 7.8 million jobs from December 2007 through September 2010 makes this the worst labor downturn since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Back then, the jobless rate surged to 25 percent, then remained above 15 percent for most of the period from 1934 to 1939. Today's downturn is not just steep but also widespread across occupations and industries (with health care a notable exception). It is also global in scope, although the US has a higher jobless rate than Britain (7.8 percent), Germany (6.9 percent), and Canada (8.1 percent).

Has anything tried so far created jobs?

President Obama's $787 billion Recovery Act, with its spending programs and tax cuts, has been the biggest effort. Smaller examples include tax rebates in 2008 under President Bush, programs to help homeowners avoid foreclosure, and tax credits for businesses that hire the unemployed.

The Recovery Act created some jobs directly, through spending that resulted in higher federal employment or new contracts with private firms. But the stimulus programs also aimed to help the job market by pumping money and confidence into the economy.

The Obama administration says the Recovery Act alone may have saved or created 3 million jobs, but that number is impossible to verify. Some critics argue that the impact on jobs has been negligible.

Would new efforts to fill the jobs hole take a different approach?

Yes, probably. On both the political left and right, many policy experts say it's time to put less emphasis on trying to find quick fixes and more on laying better foundations for long-run growth.

Conservatives say efforts vital to growth include limiting the size of government and adjusting taxes to maximize incentives for working and investing.

Liberals share some of that fiscal-reform emphasis, but also focus on investing in "human capital" (education) and infrastructure that supports business activity.

This doesn't mean that shorter-term ideas won't be considered as well. Because the housing-market collapse played a central role in the recession, some economists say more should be done to help borrowers avoid foreclosure – freeing them to spend more. Mr. Obama has tried this, but so far the efforts haven't appreciably stemmed the foreclosure tide.

Specifically, what new policies might be tried?

The main ones talked about in Congress and the business community would:

•Grant a payroll-tax holiday. Firms could skip Social Security and Medicare payroll taxes for a year or more. The idea is based on a conservative principle: If you want more of something – employment, in this case – tax it less. The payroll-tax break would complement the existing Hiring Incentives to Restore Employment Act. Some proponents say the impact would be greatest if the tax is permanently scrapped. Economist Robert Shapiro, with the liberal NDN think tank, says one way to pay for such a move would be a tax on carbon emissions to kick-start a transition from fossil fuels.

•Extend the Bush tax cuts. Republicans argue that renewing the tax cuts when they expire at year-end would boost employer confidence. In their "Pledge to America" plan, they would combine these other steps to reassure the private sector: cuts in other discretionary federal spending and an effort to slow the pace of new regulations.

Many Democrats argue for a tax-cut extension that's short term (a couple of years) or partial (excluding the rich). If the cuts expire, the economy could feel a 2 percent dip in GDP early next year, economists at Goldman Sachs estimate.

•Get the government's fiscal house in order. Any steps that restrain the rise in government debt (even if the changes aren't immediate) could give confidence to investors, businesses, and consumers. This in turn could spark spending and hiring, as Americans conclude that a debilitating debt crisis is less likely. Advocates of this idea don't recommend an immediate sharp cut in federal spending, given the current fragile recovery. But in a new Brookings Institution report, William Galston and Maya MacGuineas argue that high public debt is harming the economy, and that reforms leading to fiscal restraint are likely to boost economic growth.

•Increase government spending on strategic infrastructure such as energy security and university research facilities. Many economists argue that this will keep the US at the forefront of innovation and high-wage jobs. For budget hawks, the trick is to distinguish vital goals from pork-barrel projects.

•Promote exports. Economists agree on the goal of a more balanced economy, with stronger exports and less borrowing from abroad to finance imports. But there's less agreement on how to do that. Some call for a tougher tack with trade partners. Until this happens, says Peter Morici of the University of Maryland, China will keep manipulating its currency, subsidizing exports, and raising barriers to American imports. If US exports rise, and if Americans buy more US-made goods, that will create jobs. (The risk: a possible "trade war" that closes off some benefits of international trade.) The Obama administration aims to double US exports within five years, to create up to 2 million new jobs. But economists say it would probably require strong economic growth overseas and a big shift in exchange rates to achieve that goal.

•Give another monetary boost. The Federal Reserve – having already dropped short-term interest rates to near zero percent – has signaled that it may try "quantitative easing." In this plan, the Fed would buy assets such as Treasury Bonds to push up the prices of financial assets and expand bank lending.

•Calm the foreclosure wave. Tackling the default and foreclosure problem would help clear the way for a recovery in home prices and in the health of banks. The 11 million mortgage borrowers who are "underwater," with negative equity in their homes, are a big damper on the spending needed to rev up economic growth. After all, it's hard for the Federal Reserve to pump life into the economy via ultralow interest rates if banks are reluctant to lend and relatively few customers are trying to borrow. A program reducing loan defaults and improving household finances would coax banks to write down the principal value of at-risk loans. (See related story, page 20.)

•Repair other avenues of finance. Businesses not only face a poor climate for borrowing, but also a bad environment for raising equity capital, such as by issuing stock. In a survey of venture capitalists this year, the National Venture Capital Association found more than half citing both "unfavorable tax policies" and an "unstable regulatory environment" as problems. Some industry leaders propose a federal task force to improve the funding climate for firms in both their early stages and their later initial public offerings on the stock market.

Obama has proposed some tax changes that would help nurture innovative companies. He wants to make a tax credit for research activity permanent..

•Open doors to more highly educated immigrants. Many of the best and brightest from other nations study in the US and then head home to pursue careers. A system of green cards for advanced degree holders could help fuel an entrepreneurial boom and the jobs creation that goes with that.

•Do more to retrain displaced workers. A more skilled workforce doesn't guarantee more jobs, but training is key to growth in high-wage employment. Democrats have proposed a Community College Technology Access Act, to fund classes for the many jobless workers who lack computer skills.

Are there more radical ideas?

Sure, but the most radical proposals have a harder climb in partisan Washington than more mainstream ideas. Some examples:

•On the right, some argue that eliminating or temporarily halting the minimum wage would encourage employers to hire many young or unskilled workers who have been hit hard by the recession.

•On the left, some call for a government effort to directly employ people, reminiscent of the 1930s.

•Another approach, with fewer bureaucratic challenges, is "work sharing." Employers would be encouraged to ask employees to work less, so that jobless people could be hired part time. The government would cover the pay shortfall of current workers who see their hours cut.

How much difference can a jobs policy make?

Economists generally predict a slow jobs recovery under any scenario. But a good set of policies might accelerate the process, while missteps or inaction could slow it down or stymie it altogether.

And timing is important. Although politicians are focused now on the election campaign, some economists say the next half-year or so is a danger zone with a significant risk of relapse into recession.