US jobs: In China trade fight, does protectionism help, or hurt?

Loading...

| New York

Almost everyone in Rumford, Maine, (pop. 4,953) knows someone who works at the local paper mill, which employs about 800 workers. The town would be hard-pressed to survive without NewPage, which owns the mill and pays 55 percent of Rumford's property taxes. And, when the humidity is right, almost everyone's nose tells them NewPage is busy making paper – and money.

But this little town, where the factory is smack-dab in the middle of the business district, is also along the axis of a US-China trade dispute that in some ways illustrates the burgeoning national debate over the value of free trade versus the importance of jobs in places like Rumford.

Last year, just as the recession was biting into demand, NewPage and other coated-paper companies found Chinese and Indonesian manufacturers were grabbing market share by offering their products for less money. Before long, mills in Michigan and Wisconsin had to shut down and the people of Maine – with three mills affected by the new competition – wondered what would happen to them.

"If those mills had to close that would devastate those communities," says Rep. Mike Michaud (D), whose district includes two of the plants. Mr. Michaud and the rest of the Maine congressional delegation, Republicans and Democrats, all showed up at a hearing to determine if NewPage and the other companies had been harmed. The message from the Down East delegation, says Michaud: "We just want a level playing field."

The bipartisan support of Maine's paper industry illustrates a shift in attitudes toward trade with China that is taking place in Washington. Legislators from both sides of the aisle, frustrated by years of conversations with China over the deep imbalance in trade activity between the two countries, and concerned over plant closings in their districts, are beginning to take action.

"In the US there is a combustible mix of midterm elections, a rising trade deficit, and the weak jobs picture," says Eswar Prasad, a professor of trade policy at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., and a former head of the International Monetary Fund's China division.

On Sept. 29, the House, in a bipartisan vote, passed legislation aimed at China's management of its currency, the yuan. For years, as the Chinese exported goods to the United States, they were paid in dollars, which they have invested in US Treasury bills. But rather than let the market decide the yuan's value, the Chinese kept it at a level that US administrations have deemed artificially low. This helps Chinese exports remain competitive and makes US goods in China more expensive.

If the Senate passes similar legislation – and President Obama signs it – the Commerce Department could view currency manipulation as a trade subsidy. That would allow the US to impose additional tariffs on goods from countries manipulating their currency. It's unclear, however, if the legislation would pass muster with the World Trade Organization (WTO), the global referee for trade disputes.

The trade issue also resonates with the White House, which is looking to create jobs at no cost to the US Treasury. When Mr. Obama was in New York recently he met for two hours with China's prime minister, Wen Jiabao. Reportedly, most of their time was spent arguing over the value of the yuan.

But, as the White House is learning, China is unhappy with the US, too.

"At the same time, in China there is a growing sense the Chinese are not receiving the respect they deserve given their economic might," says Mr. Prasad.

For example, in late September, China increased its tariffs on poultry imports from the US from 31.4 percent to 105.4 percent. The Chinese had started their investigation into US poultry prices almost immediately after the Obama administration a year ago had imposed heavy tariffs on Chinese tires.

"Clearly, protectionism does not go unanswered," writes Molly Castelazo, executive director of FutureofUSChinaTrade.com, an online forum, in an e-mail. "Earlier this year President Obama announced a plan to double exports in 5 years, yet he's not going to achieve that goal if China has imposed tariffs on US goods that make these goods prohibitively expensive."

Ms. Castelazo accepts that protectionism can "save" American jobs, but at a cost. Citing a study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, she says the cost to the economy from protectionist policies runs to $100 billion a year in higher prices for goods.

For example, the bank found that tariffs saved 226 jobs in the luggage industry at a cost of $1,285,078 per job saved, some 605 jobs in softwood lumber at a cost of $1,044,271 per job, and 168,786 jobs in apparel and textiles at a cost of $199,241 per job.

Protecting one industry can also harm another, she notes: Higher prices may help companies making a product like steel but hurt the users of the product, such as the auto industry. That's one reason 36 groups ranging from the National Retail Federation to the American Soybean Association sent a letter to House leaders expressing opposition to the China currency legislation.

In fact, some free-trade proponents can point to jobs created by the imports. For example, 58 percent of the trade moving through the Port of Long Beach in California originates from China.

"A reason why there are so many longshoremen, truck drivers, warehouse workers, and others in the supply train working at good jobs is because of our trade with China," says Richard Steinke, executive director of the port.

These are not minimum-wage-type jobs, says Mr. Steinke. The average port worker makes more than $100,000 per year.

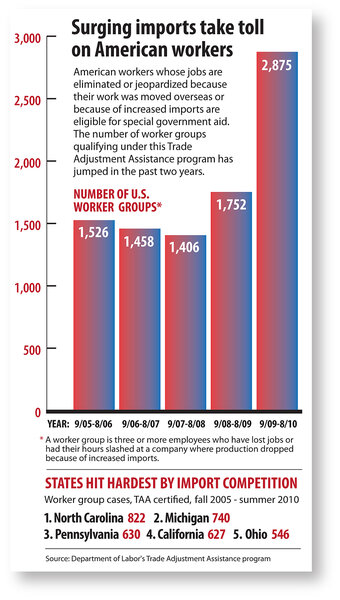

But some economists say far more jobs are lost because of current free-trade policies than gained. Robert Scott, a senior economist at the nonpartisan Economic Policy Institute in Washington, estimates that since China was admitted to the WTO in 2001, the US has shed 2.4 million jobs. Now that the US trade deficit with China is starting to rise again, Mr. Scott expects the US will lose another 400,000 jobs this year.

Michaud estimates that since 1993, when the North American Free Trade Agreement was ratified, Maine has lost 40 percent of its manufacturing base.

In Rumford, residents are concerned about the prospect of losing good-paying jobs. The average hourly pay at the mill is $26.36, not counting benefits.

"If the mill had to shut down it would be crippling," says town manager Carlo Puiia. "Not just for Rumford, but all the surrounding towns."