Hurricane Katrina anniversary: Can New Orleans' new mayor revive the city?

Loading...

| New Orleans

Mitch Landrieu now owns the legacy of hurricane Katrina.

He was not mayor then. Moreover, he was defeated by incumbent Mayor Ray Nagin in an election only seven months after the hurricane left 80 percent of the city under water.

But he is mayor now, having taken office in early May, and it is now his challenge to bring to New Orleans the hoped-for post-Katrina renaissance that has never fully taken form in the five years since.

IN PICTURES - Hurricane Katrina: 5 years later

For much of the nation, this month – the fifth anniversary of the storm – marks a moment to chronicle how far New Orleans has come. But for voters in New Orleans – and for the man they elected earlier this year – it is time to address how much further the city needs to go.

Yes, Lower Ninth Ward resident Diedra Taylor has her home again, but she has no neighbors and 10-foot-high grass swallows swaths of empty blocks around her.

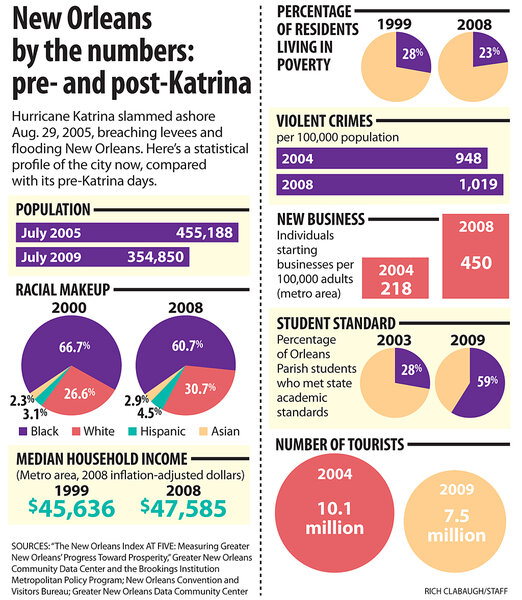

Yes, tourism has recovered from its 2006 post-Katrina lows of 3.7 million visitors, but last year's total – 7.5 million – is well below the 2004 peak of 10.1 million.

And yes, Mayor Nagin is gone, but his regime's legacy is perhaps Landrieu's greatest challenge: a $67.5 million deficit and little in the way of progress against New Orleans' endemic corruption.

For his part, Landrieu finds hope from the very fact that he was elected to solve this predicament.

He is the first white mayor of New Orleans since his father, Moon, was mayor in 1978 – and he was swept into office with 66 percent of the vote in a six-way race. In other words, New Orleans turned its back on a long history of racially divisive politics – emphatically – to elect Landrieu.

"I am the same person I was four years ago," (when he lost to Nagin), "but the people made a different choice," he says during an interview conducted in his city hall office. "What's becoming clearer to us is, as much as we ask the federal government to help … people here now instinctively know that it's our responsibility to turn the city around. And if we don't make good choices, and we don't keep after it, the city won't succeed."

Success, however, is not always easy to define. Certainly, the town is no longer a tableau of destruction, with broken levees and 182,000 destroyed homes. There are new start-up businesses, tidy homes set amid immaculate landscaping, and, of course, the French Quarter – still robust.

Yet 50,076 homes remain "blighted" – 23 percent of the city's residential addresses, according to "The New Orleans Index at Five," a Brookings Institution report. That's down from one-third of the city's residences being deemed blighted in 2008, but it still puts New Orleans far behind other economically troubled cities such as Flint, Mich.; and Detroit.

Blight was a problem even before the storm, but Katrina accelerated it, says Sam Rykels, assistant secretary of the Louisiana State Museum. New Orleans' historic character is now "in precipitous decline," and it will take considerable "political will" to change the city's property rights laws so decaying buildings can be reclaimed, says Mr. Rykels.

Resident Ms. Taylor of the Lower Ninth Ward has her home back thanks to Make It Right, the foundation created by actor Brad Pitt – and for that she is grateful. But sitting in her home directly across the street from the portion of the levee that broke in 2005, she feels almost as though she is living on a remote Midwestern homestead, not the middle of the Big Easy. The house sits amid silent plots of untamed grass.

"It's hard to have faith in politicians here," says Taylor. "I have no neighbors. My kids have no kids to play with. You can't even get the city to cut the grass."

It's now Landrieu's job to cut the grass, find neighbors, and rejuvenate the Lower Ninth. In short, he has to win the hearts and minds of residents like Taylor.

Says John Frye, a Bourbon Street Lucky Dog vendor, "[Landrieu's] got a big mess to clean up."

The mayor started by targeting a New Orleans staple: corruption. Landrieu slashed the salaries of city council members, oversaw the auditing of the city's budget, created stricter rules for use of city-owned vehicles, and redrafted the system for dealing with outside contractors. He also announced 138 projects to upgrade fire departments, libraries, recreation centers, and health clinics.

Moreover, he's named a reform-minded police chief, and he says he is investigating how and when governance of the city's public schools should be transferred back to local officials. State officials have run the school system since Katrina, with students showing dramatic improvement.

But his grander plans involve hopes of broadly recasting New Orleans' economy. And he is blunt about what needs to happen to make that a reality: better schools and lower crime.

"Everybody comes down and says, 'I love the people, it's real, there's nothing false about that place … but the crime is high, the schools are no good, and you can't make a living,' " he says. "No matter how many tax incentives I give away, if the city's not safe and the city doesn't produce smart people that can [fill] the jobs, I could give them away and [businesses] still wouldn't come."

Like many before him, Landrieu is counting on New Orleans' bedrock bohemian ways and unique character as a magnet. But he also wants to branch out.

He envisions New Orleans becoming a center of film and digital media production, a leader in biomedical research and technology, and – using the Gulf oil spill as a catalyst – a clean and renewable energy research hub for the oil and gas industry.

"Wouldn't it be a great story of resurrection and redemption if BP, rather than being forced to do everything, decided that it really wanted to change its behavior and become the model for clean energy in the world and move their [US] headquarters from Houston to New Orleans?" he asks.

The mayor's desire to diversify the New Orleans economy through knowledge-based industries is right on target, says Amy Liu, deputy director of the Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings.

The city's entrepreneurial culture has "skyrocketed since Katrina" and remains its primary strength, says Ms. Liu.

"Most of the new business start-ups [since Katrina] were by individuals in the construction and tourism and hospitality sectors, but it doesn't mean there isn't the capacity to start businesses in other sectors," she says.

For the time being, Landrieu is operating on goodwill. His father, who was mayor between 1970 and 1978, was well regarded as a progressive by rich and poor, black and white.

But in the long run, his political connections to the Washington establishment through his sister, Sen. Mary Landrieu (D) of Louisiana, might prove more important.

For example, a 2009 report by the National Academy of Engineering and the National Research Council suggests that the US Army Corps of Engineers' $15 billion, 100-year flood- protection plan, due for completion in 2012, is not guaranteed to stand firm against Category 5 hurricanes.

Landrieu says he is "not comfortable" with that assessment and suggests that President Obama will need to intervene.