Gulf oil spill: The story so far

Loading...

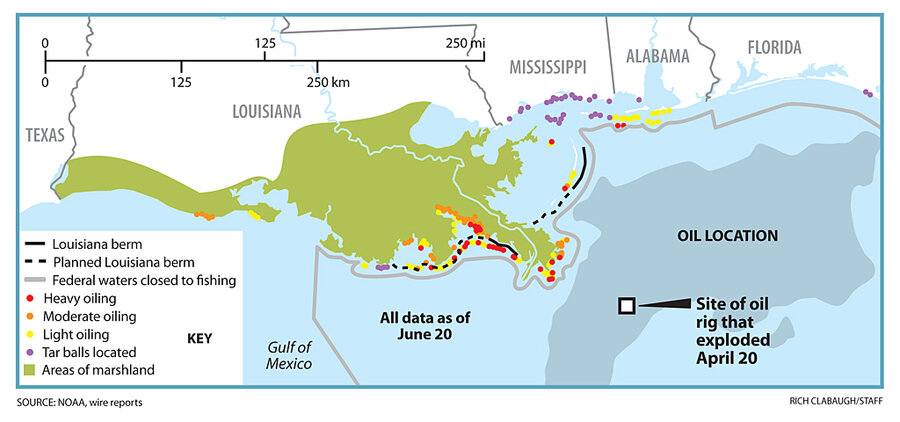

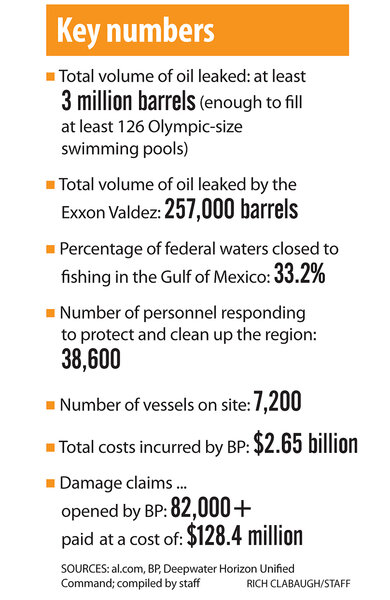

Since the Deepwater Horizon rig explosion April 20, BP and the federal government have struggled to control the oil spill that has followed. The complex effort has involved several attempts to stem the flow of oil at the wellhead, amid uncertainty about how much oil, exactly, has been flowing into the Gulf of Mexico. Now in its third month, the Gulf oil spill seems likely to continue at least until August. Here is an accounting of some of the most important – and confusing – developments.

What's been done to stop the oil flow?

May 29 was a turning point in BP's efforts at the bottom of the Gulf. That was the day the so-called "top kill" effort – BP's only bid to stop, rather than contain, the flow of oil – failed. The result: The company essentially admitted defeat in its bid to turn off the spigot before August.

Now, the only way BP believes it can shut down the well permanently is to drill a relief well that intersects the leaking well. Then, BP plans to pump heavy drilling mud through the relief well into the leaking well to slow the flow of oil. It could then cement the leaking well near the source.

The primary relief well and a backup are scheduled to be finished at some point in August. The task of intersecting a well with a relief well, however, is difficult and could require several attempts, pushing back the actual shutdown date.

Until then, BP is trying to limit the damage by collecting oil at the source.

After two failed attempts to collect oil via a containment dome and then a siphon, BP tallied its first success with a containment cap in early June. In short, BP cut the riser pipe that once led from the blowout preventer to the surface – it had fallen to the seafloor like a crumpled garden hose – and replaced it with a cap.

The cap has been doing its job reasonably well, although a June 23 mishap meant that it had to be removed for a day. When it is working, it has captured about 15,000 barrels of oil a day (630,000 gallons), which have been processed on the surface by a ship called the Discoverer Enterprise.

On June 16, a second ship, the Q4000, linked to a valve on the side of the blowout preventer and began burning off about 10,000 barrels a day. A third ship with the capacity to burn 25,000 barrels of oil a day, the Helix Producer, was set to hook up to another valve on the blowout preventer by June 29. High seas forced a delay in that plan. Coast Guard Adm. Thad Allen, who is leading the federal response to the spill, said that the ship will proceed with its mission as soon as conditions permit.

The Helix Producer is expected to be involved in oil collection for the foreseeable future. The Q4000 is scheduled to be replaced by a ship with larger capacity – 25,000 barrels a day – in mid-July.

Still, the containment cap is essentially a stopgap measure. BP would like to replace it with a more robust cap, called the overshot tool.

The overshot tool promises several advantages: It could capture more oil, in part because it would be bolted directly to the blowout preventer, potentially providing a better seal. Also, it would have two, more-flexible risers that ships could connect to and disconnect from more easily in the event of a hurricane.

The danger is that the existing cap would need to be removed, allowing oil to flow freely until the new one is affixed. Moreover, the current system is the only one that has worked.

A decision on whether to stick with the containment cap or to shift to the overshot tool will be made in early July, said Adm. Allen.

What are the flow-rate estimates?

Four days after the Deepwater Horizon rig exploded, there was a mounting sense that the disaster was not finished. Some 1,000 barrels of oil a day could be leaking into the Gulf, news reports suggested.

Fifty-two days later, scientists hazarded a different guess as to how many barrels of oil were leaking into the Gulf daily: 35,000 to 60,000.

What happened? Put simply, BP had little incentive to revise early estimates – even when it became obvious that they were grossly incorrect – and, eventually, the government stopped trusting them.

The 1,000-barrels-per-day estimate actually survived for only a few days. The estimate that followed – 5,000 barrels a day – remained the official figure for nearly a month. It was based on evidence collected at the surface by the Coast Guard and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

But when underwater video of the gusher became available, it was immediately apparent to independent scientists that that number was fanciful in its understatement. The range they suggested: anywhere from 20,000 barrels a day to 100,000.

BP, for its part, didn't budge. "We're not going to take any extra efforts now to calculate flow there at this point. It's not relevant to the response effort, and it might even detract from the response effort," a BP spokesman told The New York Times.

The federal government, sensing BP's unwillingness to investigate a subject that could harm it both legally and in the arena of public opinion, convened a flow-rate panel on May 20.

Over time, the panel has refined its estimate as more data have become available. It began with a range of 12,000 to 19,000 barrels a day on May 27, then increased that to 20,000 to 40,000 barrels a day on June 11.

When BP fitted the containment cap, the panel could compare what it saw with the amount that BP was capturing, giving it a statistical base line. On June 15, the panel came out with the 35,000 to 60,000 estimate.

On June 18, Allen said he believed that 35,000 barrels was closer to the real number.

What has the government done?

Interior Secretary Ken Salazar neatly summed up the Obama administration's take on its own responsibilities in the Gulf oil spill when he said the government's job was to "keep the boot on the neck" of BP.

Incapable of taking over from BP at the wellhead and unwilling to displace the web of contractors leading the cleanup at BP's behest, the administration has taken on the role of foreman on the Gulf relief shift.

Sometimes it has forced BP's hand – as when it pushed BP to speed up containment efforts at the well. Sometimes, it has been ignored – as when BP refused to switch to a more effective and less toxic dispersant.

On June 16, President Obama forced BP's hand in a different way: The administration established a $20 billion escrow account – funded by BP – from which all damage claims are to be paid. The account will be managed by Kenneth Feinberg, who ran the 9/11 Victim Compensation Fund.

The Obama administration has also made several broader decisions in the wake of the Deepwater Horizon blowout.

On May 11, Secretary Salazar announced a plan to reform the Minerals Management Service, the federal agency that has overseen the oil industry. Part of the problem was that MMS received royalties from the very oil companies it was charged with regulating. The Obama administration wants to split these functions – oversight and royalty collection – into two separate agencies.

On May 27, Mr. Obama announced a six-month moratorium on leases for deep-water drilling. Obama called this a necessary "pause" while his presidential commission considers what safety measures need to be introduced or strengthened.

On June 22, however, a federal judge struck down the moratorium, which Louisiana had said was costing its vital offshore oil industry as much as $330 million a month. The Obama administration will argue its appeal of the decision on July 8.

How are dispersants being used?

The use of chemical dispersants in oil spills is considered by many experts to be the lesser of two evils. But never before have dispersants been used on such a scale. As of Monday, 1.58 million gallons of a dispersant called Corexit had been used both on the surface and at the well.

This has made scientists even warier of the effects that dispersants might have on marine ecosystems. In particular, Corexit is less effective and more toxic than 12 other brands on the market, according to tests by the Environmental Protection Agency.

On May 20, the EPA told BP to scale back its use of dispersants at the surface, and it gave BP 72 hours to begin using a more effective and less toxic brand. BP has not complied.

Four Gulf fishermen have filed a lawsuit against BP, arguing that Corexit is four times more toxic than the oil itself.

What is the impact on wildlife?

The Gulf oil spill has long since surpassed the Exxon Valdez as the biggest nonland oil disaster in US history. Yet in terms of wildlife killed, the Gulf spill is dwarfed by the Exxon Valdez. As of June 29, 1,165 seabirds, 436 sea turtles, and 51 mammals had been found dead in the Gulf. By comparison, the Exxon Valdez left at least 35,000 seabirds and 1,000 otters dead.

The difference is that the Gulf oil spill is happening in the open ocean, 50 miles from the coast and a mile deep. The Exxon Valdez ran aground much nearer shore and in a far more confined area.

Some scientists worry that this means the greatest ecological impact of the Gulf oil spill is unseen, below the surface. Researchers have found tenuous plumes of diluted oil far from the well, and even low concentrations of oil or dispersant could be toxic for tiny animals crucial to the food chain, they say.

Related: