BP oil spill: Next step is to attach a giant garden-hose seal

Loading...

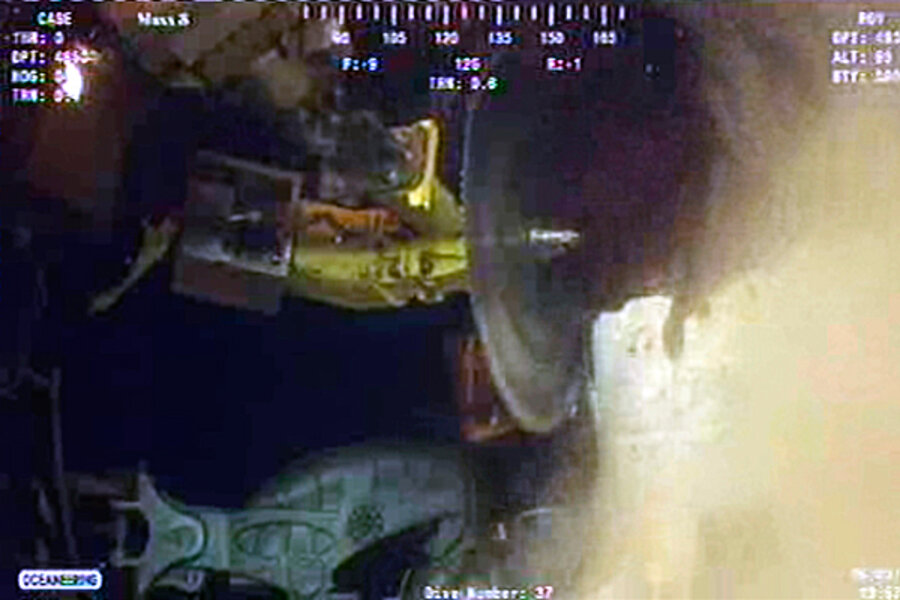

Embattled oil giant BP made headway in containing the gushing Macondo well Thursday morning, severing a piece of riser pipe to make way for a "top cap" device with a garden-hose-type seal designed to siphon leaking oil to surface tankers.

The "top cap" is Plan D in the 44-day effort to stop the leak. If successful, it could largely stem a flow estimated to be pouring as much as 19,000 barrels of oil a day into the Gulf of Mexico. BP had a temporary setback Wednesday, as a gambit to use a diamond-bit saw to make a fine cut of the riser pipe failed after the saw became stuck in the pipe. Overnight, large metal cutting shears were used instead.

Once the top cap is fitted, "we could be lucky and there is no [oil flow], but there could be some," said incident commander Adm. Thad Allen of the US Coast Guard on Thursday.

IN PICTURES: Louisiana oil spill

A government oil-flow study group estimated that, after the robotic subs at the site cut the pipe, up to 20 percent more oil could escape. It was not clear Thursday morning if more oil is escaping now, as BP attempts to move the top cap into place.

Currently, the well is emptying at a pressure of 9,000 pounds per square inch (psi). The pressure of the water at 5,000 feet is counteracting that pressure and bringing the flow pressure at the wellhead to 3,500 psi. For comparison, a crocodile's bite is measured at 5,000 psi.

"The question is, will the pressure of oil going up into the much smaller pipe mean that [it will create] enough pressure to force the oil up and around the oil seals," says Allen. "We won't know until the cap is seated and we can see how the seals are doing their job."

As BP tries to contain the oil, it faces possible criminal probes and sinking market value. The well, which blew out on April 20, killing 11, is causing what President Obama has said is the worst environmental disaster in US history. Earlier attempts to kill the well included activating a faulty blowout preventer, placing a cofferdam over the wellhead, and attempting a "top kill" maneuver by jamming heavy drilling mud into the well.

The current approach seems similar to the cofferdam gambit. That one failed because methane crystals built up and blocked the flow of oil, causing the dam to rise like a balloon. But the cap being placed Thursday on the riser pipe, at the top of the so-called lower marine riser package, is smaller and has built-in manifolds that will allow BP to pump methanol into the flow to counteract the crystal buildup.

Allen conceded that a heavy hurricane season, which is predicted, could affect operations even if the cap succeeds. In the event of a storm, tankers at the surface might have to be moved, and the well would have to be allowed to flow unhindered again. A final solution, drilling two relief wells, is ahead of schedule and slated for completion some time in August, Allen says. Some scientists say that, under the worst-case scenario, the Macondo well wouldn't be capped until Christmas.

IN PICTURES: Louisiana oil spill

Related: