What is 'top kill' and when will we know if it plugs BP oil spill?

Loading...

The US Coast Guard has cleared BP to proceed with the “top kill” procedure that officials say is the most complex attempt yet to stop oil from gushing into the Gulf of Mexico. The procedure is expected to begin Wednesday, though BP and the US Minerals Management Service had not announced a start time.

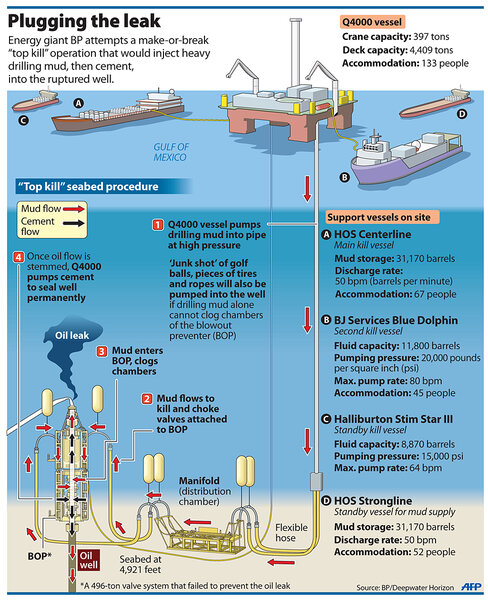

At its simplest, top kill involves pumping drilling mud at a rate of 40 to 50 barrels per minute to reduce the pressure of the oil’s flow, ultimately stopping it altogether. Top kills have been performed to address similar spills, BP officials say, but none has been done at 5,000 feet below the water’s surface.

“The pace at which we are doing this is unprecedented … [and] we need to be careful in terms of setting expectations,” said Kent Wells, BP's vice president for exploration and production.

IN PICTURES: Louisiana oil spill

The procedure requires an elaborate and precise orchestration among five vessels at the surface, whose duties range from housing pumping equipment to storing a total of 50,000 barrels of drilling mud, and several remote-controlled undersea robots. If all goes as planned, the dense mud will be pumped through a single 6-5/8-inch-diameter drill pipe from one vessel, which will then enter two 3-inch-diameter hoses. Those hoses will deliver the material to the sea floor, where they will intersect with the choke and kill lines of the damaged blowout preventer, which sits atop the well.

On Monday BP Chief Operating Officer Doug Suttles defined success as halting the flow of oil from the well. If the procedure is launched early Wednesday, “by Wednesday evening we should know if it’s successful,” he said.

If the flow is stopped, the well would then either be permanently sealed with concrete or be covered by a second blowout preventor to replace the one that failed April 20, the date of the explosion that initiated the crisis, Mr. Suttles said.

The procedure is not without risk. The condition of the well’s bottom remains uncertain, and fractures in the rock may prevent the mud from having a solid enough base to exert pressure against the oil so that its flow is reversed.

The direction of the mud entering the well is also problematic because it will be driving into the well from both its sides, not from the top, which may strip the mud of the kinetic energy it needs to push the oil down, says Bruce Johnson, professor emeritus of oceanic engineering at the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md.

By injecting the mud sideways, “they’re really depending on the weight of the mud to force [the oil] back down the tube,” Dr. Johnson says. “I think that’s going to be tough.”

US Coast Guard Rear Adm. Mary Landry has said she is “optimistic” that top kill will work, but she told reporters last week that plans are in place in case it fails. “We have be to ready for the long haul to see this through,” Landry said.

If the top kill fails, one risk is that it could end up eroding the riser, a now-broken pipe connected to the wellhead, and increasing the well’s flow of oil, Suttles said Monday.

If that happens, BP plans to cut the riser and place another containment dome over the leak. Another option on the table is launching the “junk shot,” which is an injection into the well of materials ranging from rubber tire shards to golf balls. The procedure was planned weeks ago but dropped once it was determined it would risk the effectiveness of the top kill, Suttles said.

IN PICTURES: Louisiana oil spill

Related: