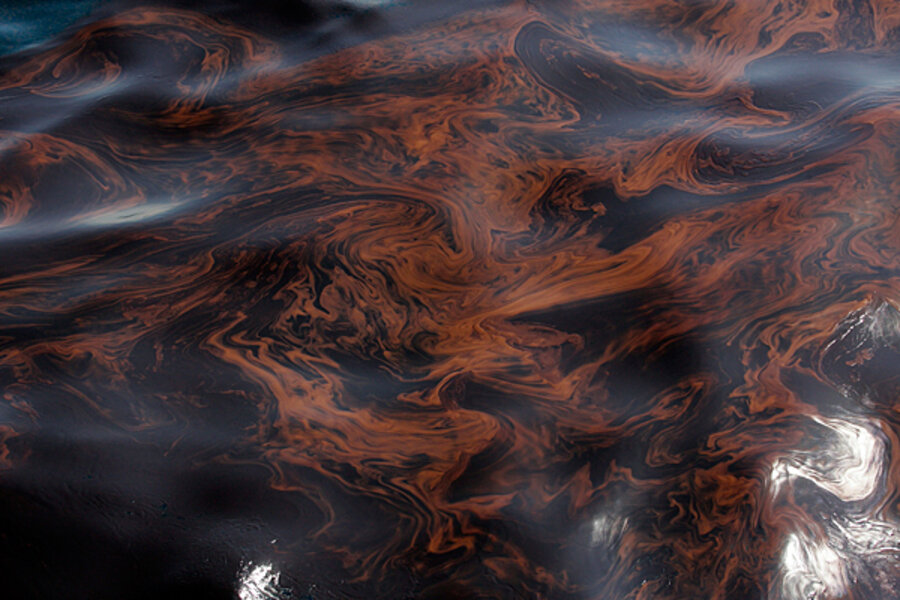

Oil spill: Gulf of Mexico burn is last-ditch effort to stop landfall

Loading...

The decision by the Coast Guard to set fire to parts of the Jamaica-sized Gulf of Mexico oil spill spreading toward the Gulf Coast is a sign of mounting desperation in efforts to prevent oil from the sunken Deepwater Horizon oil rig from reaching American shores.

Though burning crude oil has been done experimentally, most notably off the coast of Newfoundland in 1993, it's a last resort, and indicates that dogged attempts to both contain the spill and stanch the 42,000 gallons of crude a day spilling out of a crumpled "riser" have largely failed.

On Wednesday, the slick crept to within 20 miles of Louisiana's sensitive fish nurseries and bird rookeries. There's now a "high probability" that oil could reach the Pass a Loutre wildlife management area Friday night, Breton Sound on Saturday, and the Chandeleur Islands on Sunday, according to the AP.

IN PICTURES: Louisiana oil rig explosion

"This is potentially a very serious issue.... We are under no illusion of the risk that's involved here," Coast Guard Commander Thad Allen said in Miami Tuesday, according to Reuters.

Few other options

The Deepwater Horizon oil rig blew up last Tuesday, killing 11 and injuring 17. Some 36 hours later the rig sank, and since then oil has continued to spew from the wellhead sitting 5,000 feet below the surface of the Gulf of Mexico in the Mississippi Canyon.

A joint task force of industry groups and federal agencies have stretched their capabilities to the point that it has few options other than to attempt the oil burn.

In the Newfoundland experiment, 13,000 gallons of crude were tightly corraled in a fireproof boom and set alight with a so-called Helitorch. The burn took about an hour, and the summary from researchers was that burning is a viable way of dealing with an oil spill in an emergency.

But in the current case, the Macondo wellhead could spill more than 4 million gallons of oil (the Exxon Valdez spilled 11 million gallons). Given the difficulty in containing the spill so far, the total volume of oil, and the relative infancy of emergency surface burns, however, the task force will have to start small. Its plans are to corral a 500-foot-long section of the oil spill with a fire-resistant boom, tow it to a remote area, then burn it, according to a statement.

If this works the task force will repeat the process in a series of controlled, one-hour burns, the statement added.

Charges coming?

Meanwhile, Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano and Interior Secretary Ken Salazar said Tuesday they'll investigate possible criminal or civil violations on the part of Swiss-based Transocean, the contract driller, and other related companies, as a result of the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

The incident is adding political pressure to President Obama's plan to expand deep water oil exploration along the US coast.

The fire and plume may not be visible from land, but the prospect of swaths of the Gulf burning for potentially weeks on end could raise more questions about the safety and viability of more offshore drilling.

"Maybe the biggest risk the offshore industry has had all along is the public relations risk, and the way this is unfolding it could be an incredible public relations disaster," says Robert Bryce, author of "Power Hungry: The Myths of 'Green' Energy and the Real Fuels of the Future."

IN PICTURES: Louisiana oil rig explosion

Related:

Oil spill: Gulf of Mexico disaster 'growing by the moment'

Oil spill: Gulf of Mexico Deepwater Horizon slick can be seen from space

Spread of Gulf oil spill puts fragile Louisiana Coast on alert