Why solving the Asian carp problem is so hard

Loading...

| Chicago

The scenario seems lifted from a Hollywood disaster movie: a creature poised to invade the water system of a great American city eats everything in its path and reproduces so quickly that its invasion could mean the death of most other living things in the water.

The reality may be just as frightful.

The Asian carp, a filter fish known to consume one-third of its body weight in a day, has found its way to the doorstep of Lake Michigan, which environmentalists say spells disaster for the Great Lakes ecosystem and threatens to destroy the $7 billion in recreational fishing and tourism revenue generated each year.

"Stopping the Asian carp invasion is perhaps the biggest ecological challenge of our generation," says Jennifer Nalbone of Great Lakes United, a coalition of advocacy groups dedicated to protecting the Great Lakes.

IN PICTURES: The 20 weirdest fish in the ocean

How to do it is another matter.

In December, a single Asian carp was discovered about six miles from Lake Michigan's Chicago shoreline. Since then, Illinois has come under criticism from neighboring states, which say Illinois and federal lawmakers are not doing enough to stop the invasion.

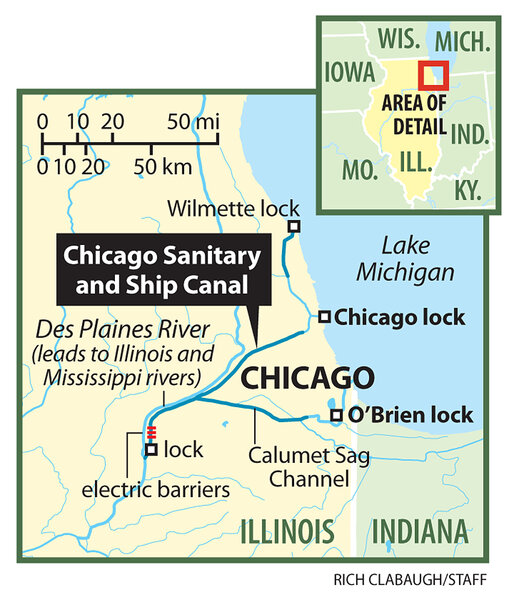

Michigan, which is leading a lawsuit, wants Illinois to immediately close the O'Brien Lock and Dam in the Calumet-Sag Channel and the Chicago Controlling Works in the Illinois River. The idea is to prevent the fish from entering Lake Michigan.

In January, the US Supreme Court denied a petition to seal off the lake. On the same day, the US Army Corps of Engineers discovered DNA that showed Asian carp had already breached the locks and were in Lake Michigan waters.

Stopping further reproduction has become a hot-button issue, prompting Michigan and a coalition of five states to petition the high court to reconsider its position.

The White House got involved in February, issuing a framework plan for preventing the fish from infiltrating the Great Lakes and committing $475 million to back it up. The plan calls for building an additional electric barrier and restoring wetlands while continuing to research the problem.

Critics say that plan has no firm timeline and does not commit to permanent closure of the navigational locks to keep carp out.

"We think the court should take another look at our request to hit the pause button on the locks until the entire Great Lakes region is comfortable that an effective plan is in place to stop Asian carp," Michigan Attorney General Mike Cox said in a statement.

The federal plan argues against lock closure, saying 14.6 million tons of the Chicago area's petroleum, coal, road salt, cement, and iron travel through the lock. The canal generates $30 million a year in revenue, according to the American Waterways Operators, a trade association representing the tugboat, towboat, and barge industry.

But even if the locks are closed, Lake Michigan is still under threat from Chicago sewage.

The Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, which connects the lake to the Mississippi River, was built early last century to reverse the flow of Chicago wastewater, pushing it downstream from the lake.

Thomas Murphy, former editor of the Journal of Great Lakes Research, says closing the navigational locks would allow water to resume its historical flow. The problem, he says, would come when storms cause wastewater treatment plants to overflow. Without locks to release it, sewage would run into the lake.

Mr. Murphy estimates that 11 billion gallons of untreated sewage overflowed into Lake Michigan last year. "So it happens now," he says, "but it would happen much more frequently, although in smaller discharges, if the locks were closed."

Already, the carp are shaking up the fishing economies of small Illinois river towns downstate, where millions of carp are destroying local crappie, bass, and bullhead populations.

"You don't find [the native species] anymore," says Kurt Hettiger, chief aquarist at the John G. Shedd Aquarium in Chicago. "If [Asian carp] keep moving in and taking up the biomass in the river, they could totally replace the [other] fish."

If Asian carp infiltrate the Great Lakes, says Mr. Hettiger, they will have access to several Midwest river systems. "The potential is there for a lot of devastation."