Number of storms may drop, but more could be intense, study says

Loading...

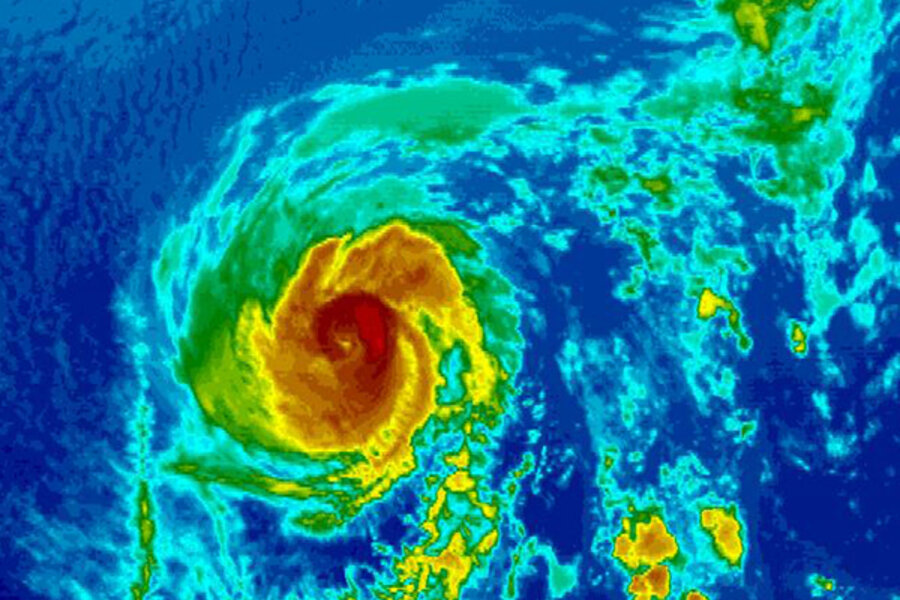

The number of hurricanes, typhoons, and tropical storms globally is likely to either fall or remain flat over the course of the 21st century. But an increasing proportion of the storms are likely to hit the highest levels of intensity because of the projected effects of global warming, an international team of scientists concludes.

However, it's unclear whether past trends in the number and intensity of storms – which some research suggested may be due to global warming – fall outside the range of natural variation. This is particularly true of the Atlantic basin, the team writes.

These results appear Sunday in the online edition of the journal Nature Geoscience.

The work updates a 2006 review of tropical cyclones and climate change, which many of the scientists on this team provided at the behest of the World Meteorological Organization. It also updates the related portions of a major survey of climate science published in 2007 by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), as well as a 2008 assessment on severe storms and global warming by the US Climate Change Science Program.

The new review represents "a chance to look back and see where the science has gone since that time," says Thomas Knutson, a researcher at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory in Princeton, N.J. He is the lead author for the review.

Many conclusions in the latest work are similar to those in past assessments. But some differ in significant ways. This illustrates the changes that scientists typically make to their conclusions as they continually test them.

For instance, the team notes, the IPCC's 2007 Fourth Assessment Report concluded that, "more likely than not," global warming helped fuel a rise in the number of the most intense tropical cyclones. Sunday’s review doesn't support that statement, the team writes, citing uncertainties in records for storms globally, as well as the influence of natural variability in the Atlantic.

In that region, records do suggest a recent increase in storm intensity. But it's unclear, the team says, how much of that change is because of natural swings in conditions that take place over many decades, and how much may be due to the effects of global warming.

However, the team also notes, recent research allows for a higher degree of confidence that in the future, the overall number of storms "more likely than not" will decrease globally, while the number of intense storms "more likely than not" will increase substantially – even though some regions may not follow the broader trend.

Using studies with a new class of improved computer models, and assuming a business-as-usual scenario for greenhouse-gas emissions, the team estimates that maximum wind speeds in those storms are likely to increase by 2 to 11 percent over the century. Also, rainfall rates are likely to rise by as much as 20 percent for distances up to 60 miles from a storm's eye.

One important factor for reducing uncertainties in such projections: getting a better hand on El Niño and its mirror opposite, La Niña, in the models, suggests Phil Klotzbach, a researcher at Colorado State University in Fort Collins who produces seasonal hurricane forecasts for the Atlantic basin. The projections of the team producing the Sunday’s report, he says, rely heavily on sea-surface temperatures (SSTs), which he acknowledges are important.

But "if future climate were to shift more towards an El Niño or La Niña-like basic state, it could easily overwhelm any changes in basin-specific SSTs," he writes in an e-mail.

-----

Follow us on Twitter.