How the world views Obama at one year

Loading...

| Paris

If there was anything Germans wanted most from Barack Obama in the first year of his presidency, it was action at the climate summit in Copenhagen, Denmark. They knew the new American president represented change.

That’s why some 300,000 Germans gathered near Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate when candidate Obama gave his main foreign-policy speech there in July 2008. (President Bush’s last state visit to Germany a month earlier was ghostlike – a media-free visit outside Berlin.)

Last summer, Germans cheered President Obama when he agreed at the Group of 8 summit to a limit of 2 degrees C on global warming. Green Party adviser Bastian Hermisson quipped it was “a giant leap for the US and one small step for mankind.”

Yet in the hapless aftermath of Copenhagen, German attention fixated not on a US president failing to spin a miracle deal, but on China’s ability to control the outcome. Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao’s repeated “No” in the key meetings was seen by many in Berlin as a historic shift – to a world in which transatlantic power is constrained and rising powers from Brazil to South Africa have new clout.

A year after the ebullient inauguration of America’s first president of color, the perception abroad of Obama is tempered by a recognition of the limits on his power. On Nov. 4, 2008, Obamamania reached such planetary peaks that it was widely felt he was elected president of the world. Dominique Moisi, a leading French intellectual, called it a “Copernican shift” in perceptions about the United States.

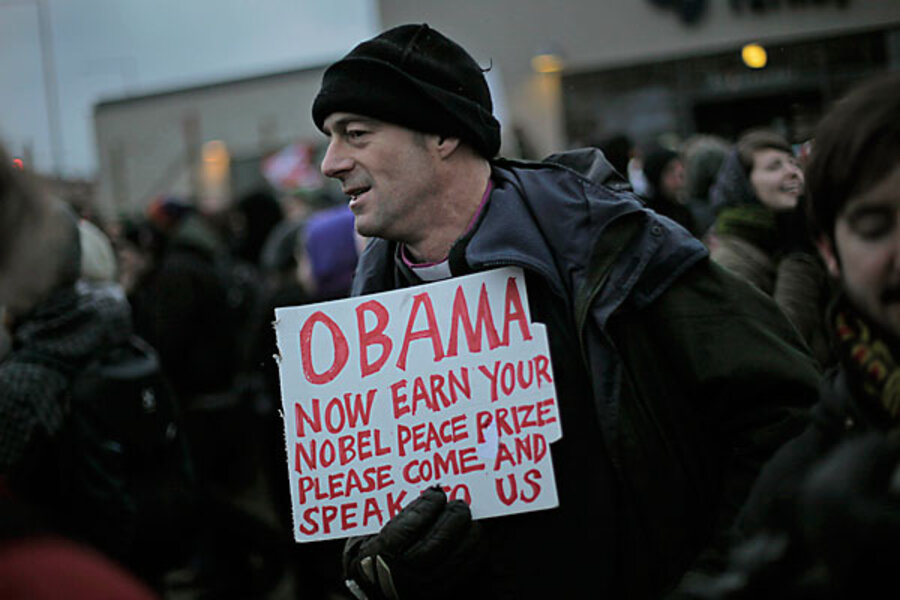

Indeed, as a symbolic figure, Obama remains, a year later, an inspiration, a “rock star,” a Jack Kennedy with African roots. He isn’t particularly liked in Israel and Russia. But his approval ratings in Africa, Europe, and Asia are strong. Obama’s poll-sapping criticism inside America from “tea party” Republicans doesn’t get great mention abroad.

In global surveys, he edges out Angela Merkel and the Dalai Lama as the No. 1 admired figure. In the past year, respect for the US has spiked, too. A GfK Roper Public Affairs & Media survey in December, conducted in 20 nations, showed the US moving from 7th to 1st among admired countries.

“While most nations’ reputations do not undergo major change from year to year, the US has clearly bucked the trend,” notes Xiaoyan Zhao, director of the GfK Roper study.

Despite growing criticism in some quarters, Obama is lauded for “changing the tone” of US foreign policy. Many experts view him as speaking to a global public in a new way on universal values. America’s “reset” on Russia is one of many policy changes by Obama designed to challenge old beliefs or conditions: In Cairo Obama said the US is not an enemy of Islam. In Prague, Czech Republic, he called for an end to nuclear weapons. At his Nobel acceptance speech he stated that “America cannot insist that others follow the rules of the road if we refuse to follow them ourselves.” In Shanghai he told students that a US-China confrontation is not destiny.

He’s given credit abroad for handling a US economy in sluggish recovery. Nightmare scenarios of a world dragged into depression, a palpable fear a year ago, have somewhat receded.

“There’s logic in the fact that Obama first took to restoring America’s image ... by adopting a radically new tone towards the outside world,” says former French Foreign Minister Hubert Védrine, “in particular the Arab-Islamic world and Russia, where the Bush team was stuck in a deadlock.”

The Chinese watched Obama walk off Air Force One in Shanghai in heavy rain, holding his own umbrella, alone. The image flashed to netizens across the country who marveled at the world’s most powerful man dealing with the rain by himself, not swarmed by aides. “He’s charming and elegant,” notes a former diplomatic translator in Beijing. “What’s not to like?”

In Paris, they loved the way Obama and the first lady visited the kitchen and hotel staff, shaking hands and smiling, countering notions that he is cold or merely cerebral.

Still, the global view in early 2010 is hardly idyllic. Obama’s grades on manifold hard problems are incomplete. Most analysts agree he was dealt a difficult hand. But, in the past half year, some experts and foreign leaders use terms like “disappointing,” “naive about Iran,” “indecisive on Afghanistan,” or “too fast on Israeli settlements.”

Critics have called him weak, a Jimmy Carter figure relying too much on American “soft power.” Human rights groups from Hong Kong to London decry the difference between candidate Obama and President Obama.

Opinionmakers and diplomats overseas remain divided. After 365 days, the consensus is still a hefty “wait and see” on new American leadership. Year 1 with Obama at the helm brought no instant utopias, rainbows, unicorns, or millenarian reconciliations between lions and lambs in the world’s far-flung hot spots. Few expected this; but in Planet Hollywood, some of the global citizenry were hoping for it after the storybook election.

“It is undeniable that Obama’s remarkable speeches and his engagement policies have helped reduce Middle East tensions significantly, albeit temporarily,” notes French intellectual Karim Emile Bitar, contacted in Lebanon. But he adds that while “the Lebanese still support Obama by a 3-to-1 margin, skepticism is growing. The dichotomy between words and deeds is becoming more obvious by the day.”

Yet publics can be fickle. Europeans spent eight years bitterly complaining about US policy. But now with a president who has 77 percent approval in much of Europe, little is being done to help Obama with issues from Russia to disarmament to Afghanistan. “Obama has already more than met our expectations of change,” notes Constanze Stelzenmuller at the German Marshall Fund in Berlin. “Yet Europe has not risen to the occasion.”

Chinese elites know Obama sees the Middle Kingdom as a high priority, which draws mixed reaction: Obama has moved away from an all-defining antiterror policy that Beijing had grown comfortable with after 9/11. Cai Jiahe of the Johns Hopkins-Nanjing Center in Nanjing, China, finds it unusual for Sino-American relations to start so smoothly with a new US president.

“The US has made apparent adjustments in its diplomatic policy,” he says. “It is intentionally dwarfing itself and thinking twice when dealing with China, which is actually a condition of winning Chinese cooperation in the future.”

New administrations make gaffes overseas. Obama’s is no exception. Poles, for example, turned apoplectic when the US announced on Sept. 17 that it wasn’t going ahead with a missile shield promised by Mr. Bush. Sept. 17 is the date in 1939 of the Soviet invasion of Poland. The White House quickly dispatched envoys to reassure Warsaw.

“Relations are restored,” says Bartosz Weglarczyk, foreign editor at the Polish daily Gazeta Wyborcza. “But it looked like Poland and East Europe were taken for granted by America and that makes Poles angry. It’s a pride thing.”

For the most part, the “wait and see” consensus on Obama abroad falls roughly into two camps: a “more time is needed” camp, and a “time is running out” camp.

The more-time theorists argue it is unrealistic to set ambitious goals on intractable problems – and expect quick results. Mr. Moisi argues that when you look at his progress on healthcare, stewardship of the economy, and overseas agenda, “Barack Obama has done more in one year than any US president.”

Much discussed in Europe and the Middle East is a new Foreign Affairs article by Zbigniew Brzezinski, President Carter’s national security adviser, called “From Hope to Audacity.” It lays out nine agendas Obama is pursuing, from treating China as both political and economic partner to starting talks with Cuba to affirming that a “global war on terror” does not define America’s role to being an honest broker in the Middle East to shifting ties with Russia.

“In less than a year, [Obama] has comprehensively reconceptualized US foreign policy,” Mr. Brzezinski writes.

Yet as Moisi also comments, “For a president who wants to make history with his action, and not only speeches, there are objective limits to the power of the word.”

For the “time is running out” camp, Obama’s inexperience is outweighing his intelligence. Perhaps the biggest disappointment is in the Arab world. Expectations were high after Obama’s speech in Cairo and his demand to freeze Israeli settlement activity. But the president’s backpedaling on settlements, combined with administration critiques of the UN Goldstone report, which called for an investigation into war crimes by the Israeli army in Gaza, brought widespread disaffection among Arabs.

Mamoun Fandy, a Middle East expert at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London, who spent Christmas in Damascus, Syria; and Cairo, says the feeling in both cities is that Obama “talks the talk but doesn’t walk the walk. Expectations after the Cairo speech were very high ... but he now looks status quo American – nothing different but color and the color isn’t coming out.” He adds: “Here people think Osama will outlast Obama.”

Still, others urge patience before pillorying him. “You can’t make a serious analysis of a president after one year – not with Kennedy, not with Reagan,” says Mr. Védrine. “But many of us in Europe feel it will be a tragedy for the world if Obama does not succeed.” ρ